By: Mildred Leedy Armao

Daniel Boone is iconized as the man who blazed the trail across the Cumberland Mountains from Virginia to Kentucky. This important route, then, opened the door for tens of thousands of pioneers to settle west of the Appalachian Mountains. Initially, the trace was simply that; a constellation of worn Indian footpaths and buffalo trails that were marked and cleared of underbrush to facilitate access to the Bluegrass Region.[1] It is commonly thought that the Wilderness Trail remained in that state, impassable to wagons, until after Kentucky attained statehood: “The road marked out was at best but a trace. No vehicle of any sort passed over it before it was made a wagon road by action of the State legislature, in 1795.”[2] Some historians acknowledge earlier gestures at improving the path but conclude that little of consequence was done until 1792.[3] Until now, little has been written to dispute either point of view but primary sources prove that the transition from Wilderness Trail to Wilderness Road began in the summer of 1780 when William McBride of Kentucky County joined forces with John Kinkead of Washington County and paved the way for wagons to pass.[4]

Gateway to the West – Daniel Boone Leading the Settlers through the Cumberland Gap, 1775 by H. David Wright, c. 2000, permission granted by the artist.

As Kentucky began to be settled there were, generally speaking, two routes for those who wished to settle there: the Ohio River or the Wilderness Trail. River travel allowed settlers to freight their possessions but was dangerous for two reasons: navigational hazards and British-armed Indians that still controlled the Ohio River Valley. Indian attacks were also a threat to those who chose the overland route, but the trail led through territory owned by Virginia and travelers could assemble at frontier stations to form large parties; there was safety in numbers. However, the land route was restricted to packhorses, which necessitated leaving bulky household items behind. As a result, four years after Boone blazed his trail, Virginia authorities addressed the need for the path to be improved for those who wished to establish permanent homes in Kentucky.

“Course of the Wilderness Road by 1785,” Wikimedia Commons, submitted by user: Nikater, March 17, 2007. Background map courtesy of Demis, www.demis.nl.

In October 1779, the Virginia Assembly passed [sic] “an act for marking and opening a road over the Cumberland mountains into the County of Kentuckey.”[5] The intent was to create a wagon road to the western regions of the state, but the Assembly recognized that the traditional method of road building, giving oversight to counties and residents along the way, was not viable for a route that traversed predominantly uninhabited country. As such, two commissioners were appointed to mark the passage, clear it for packhorses, and then report back to the Assembly with an estimate of distances between way stations and costs for the construction of a permanent wagon road. The commissioners were also asked to present an account of their expenses and, if approved, laborers and militia guards hired for duty would be paid by their choice of 300-acre treasury warrants or £120. Additionally, the commissioners were empowered to conscript local county militias for protection along the way.

Evan Shelby and Richard Calloway were specifically named as the intended superintendents for this project, but were given the option to appoint someone else to act in their stead. Shelby and Calloway were logical choices for the job. Evan Shelby resided in Fincastle County, Virginia [vicinity of present-day Bristol, Virginia] and, at the time, was Colonel of the Washington County Militia. Richard Calloway had accompanied Daniel Boone on the initial 1775 trail-blazing expedition and was a prominent resident of Boonesborough. However, according to Lewis Preston Sumners in the History of Southwest Virginia, on June 20, 1780, John Kinkead was appointed to act for Shelby and Kinkead and Calloway then completed the enterprise.[6] This cannot be true. Richard Calloway was killed by a Shawnee war party three months prior to Kinkead’s appointment.[7] An interview conducted by Reverend John D. Shane with William McBride (Jr.) in Woodford County, Kentucky circa 1842 sheds new light [sic]:

“John Kincaid, of Powell’s Valley, Evan Shelby, from somewhere there father of the governor, & Rd. Calloway of Bnsbrgh: were appointed commissioners, fall session 1779. to survey & mark a road from the Blockhouse near Abingdon, on to the Crab-Orchard. (Calloway was killed at Bnsbrgh:) Kincaid and Shelby declined going for want of a guard, as no appropriation had been made, either for personal services, or any value to be fixed upon, for such services. (no amount was specified for commissioners, was the reason Shelby & Kincaid wouldn’t act.) After this, Wm: McBride, having been appointed, started on from Hdsbgh: entirely alone. No one was willing to go with him, going in [to Washington County] because he was marking his way for men to follow. He was authorized by the law to hire hands which were to be paid in land warrants, 200 acres each. When he got in [to Washington County], he hired 60 markers & 2 wagons. Part were for a guard, which guard was commanded by Col. Murrell, senator from Madison. He died at Fkft:. His return was late in the fall.”[8]

Thus, we learn that William McBride, in fact, was the Kentucky commissioner who supervised the first effort at improving the Wilderness Road.

William McBride, a resident of Botetourt [later Rockbridge] County, Virginia, became an early settler of Kentucky when in 1776 he cleared several acres of land, built a cabin, and planted a crop of corn five miles southeast of Fort Harrod.[9] Two years later, his entire family permanently relocated there.[10] When the Virginia Land Commission began hearing settlers’ claims in October 1779, McBride was awarded a 400-acre settlement and a 1,000-acre preemption.[11] As a master blacksmith[12] he quickly became an active and respected member of the Harrodsburg settlement community. In June 1780, he signed a petition to the Virginia Assembly asking for the establishment of a town at the Falls of the Ohio [Louisville].[13] He later served as a justice of the peace for Lincoln County,[14] deputy surveyor to John Thompson,[15] and as a Captain in George Rogers Clark’s Illinois Regiment.[16] A record specifically confirming McBride’s appointment to act in Richard Calloway’s place has yet to be found, but it is believed that the county court in Harrodsburg made the choice.[17] And, while Thomas Speed states that in 1790 the Wilderness Trail was still “only a track for the weary, plodding traveler, on foot or horseback, whether man, woman, or child,”[18] significant evidence of the extent of McBride’s work on the Wilderness Road in 1780 exists.

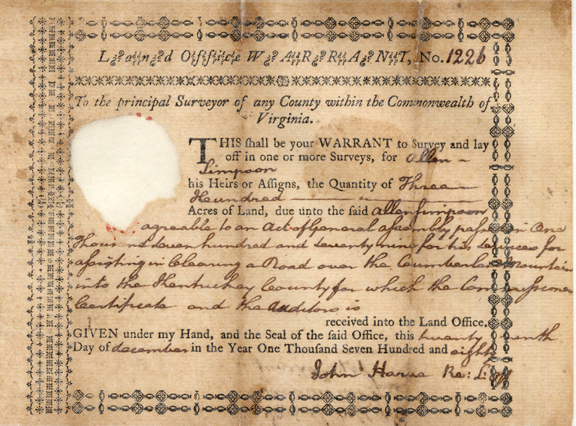

Virginia Soldiers of 1776, a compilation of historic documents from the Virginia Land Office, contains [sic] “A list of the labourers, Gard, packhorsemen and bulock drivers imployed in the service of the Rod to Kaintuck, under the derections of John Kinkead and Wm MBrid, Comiseners.”[19] This record, dated November 19, 1780, certified that 49 men were entitled to receive land grants for their work. Several names on this list are of particular interest: Joseph Lapsley, Albert McLeur [Halbert McClure], Captain James Snoddy, Allen Simson [Simpson], and Charles Bickley. William McBride was married to Martha Lapsley,[20] the McBrides and the extended family of Halbert McClure (1684-1754) were connected to one another in Augusta [later Botetourt/Rockbridge] County as early as 1762,[21] and Allen Simpson’s treasury warrant for 300 acres of land given in consideration of his service still exists.

Also extant is the pension application of Charles Bickley [sic]:

“This declarent remained at his home upon the frontier [Washington, later Russell County], and in the vicinity, engaged in many skirmishes, and performing some occasional service of great danger, but only of a volunteer character, without either military orders or compensation, until the year, he thinks, of 1780, when he was ordered out again about the month of August or September, under Captain John Snoddy, as a military guard for the opening of a new road from the valley of Holston River, via Cumberland Gap, to the settlements in the now state of Kentucky, near the Crab orchard in that state, in which service they were engaged at least two months and a half, and were then marched back to [Washington County], as well as this declarent now remembers. One Mr. McBride was the superintendant to open the road which he has mentioned.”[22]

Having thus established William McBride’s role in the improvement to the Wilderness Trail in 1780 we must now attempt to quantify the extent of his work. In 1915, Dr. Earl Gregg Swem, Assistant State Librarian of Virginia, discovered vital information for doing just that.[23] Exactly as the Virginia Assembly had directed, McBride and Kinkead submitted an invoice for expenses incurred over the course of their project. This invoice provides insight into the scope of the construction and names additional workers who did not qualify for land warrants.[24] The vouchers include, but are not limited to [sic]:

July 17, 1780: To pd Thomas Mountgomery for 69 yd Linen at 18£ per yd £1242

July 29, 1780: To pd. William McBride for repairing tools used in clearing the road £200[25]

July 29, 1780: To pd. Tho. Jenkins for herding horses 11 days @ 15 dolls. p. day £49.10

August 22, 1780: To pd. Christopher Acklen for 3 horses & one waggon £5500

September 19, 1780: To pd. Robert Hughston for 3 Beaves £900

October 10, 1780: To pd. Richard Pryer for 20 days Bullock driving at 80 dollars p. day £480

Harrison Randolph, one of three auditors for the public accounts of Virginia, approved the £54,003.11 invoice on April 20, 1781. Interestingly, 78% of the listed expenses are for food and packhorses and nearly half are dated July 29, 1780.[26]

This invoice also reveals that the total amount submitted by McBride and Kinkead was offset by £4,923.5 obtained from the sale of used or unused items to the workers when their task was complete. William McBride’s purchases are of particular interest; he spent £1,500 for 1 wagon and cloth. The fact that William McBride purchased this wagon necessarily means that it traversed the Wilderness Road back to his home at Fort Harrod; according to the testimony of William McBride, Jr. and Charles Bickley, construction commenced in Washington County, then crossed the mountains into Kentucky. The men’s rate of movement along the road, 1.8 miles per day, is also significant.[27] Coincidentally, in 1754, George Washington and the Virginia militia constructed a road across the Alleghany Mountains from Will’s Creek[28] to the Great Meadows[29] following an old Indian trail[30] at the exact same rate of 1.8 miles per day.[31] Washington’s road accommodated artillery and wagons.

So, why have historians consistently maintained that no wagons passed over the Wilderness Road until 1796? The only answer can be the dearth of testimony concerning the quality of the road or travel upon it prior to that date. A closer examination of two known sources is interesting.

In 1775, Richard Henderson of the Transylvania Company, followed Daniel Boone’s expedition and recorded his journey over the newly blazed trail. His diary, then, provides a benchmark for travel on the Wilderness Trail at its conception.[32] Henderson’s journal indicates that in 1775 wagons were able to travel the route to Martin’s Station.[33] After that, one entered the wilderness through a network of trails. Henderson’s diary further records that he travelled the 109 miles from Martin’s Station to the Dix River in ten days,[34] averaging 10.9 miles per day. At the Dix River, the Wilderness trail forked and Henderson continued north to Boonesborough; the other branch led northwest toward Crab Orchard.[35] That is the road William Brown took in 1782, just two years after McBride and Kinkead had performed their work.

Brown, too, kept a journal of his travel[36] and it witnesses clear improvement to the Wilderness Trail. Brown travelled from the Blockhouse near Gate City, Virginia to the Dix River, a distance of 162 miles, in seven days. His travel time of 23.14 miles per day beat Henderson’s by a factor of two.[37] This supports the theory that the trail was significantly improved between 1775 and 1782, posited here to be the result of McBride’s and Kinkead’s work in 1780.

Brown’s commentary is enlightening as well. The road from the Blockhouse to Wallen Ridge was deemed “generally bad” but Brown acknowledges that this particular segment courses through mountainous territory. He then states that the road from Wallen Ridge to the Cumberland Gap was “pretty good” and that the way through the Gap was “not difficult.” From Middlesboro, Kentucky to the Rockcastle River, Brown notes “very little good road” and again describes mountainous conditions in addition to mud. From the Rockcastle River to Crab Orchard the road was considered “tolerable good.” Missing is any observation that the Wilderness Trail could not accommodate wagons. In fact, between 1775 and 1790 over 75,000 pioneers settled in Kentucky suggesting that the route, while difficult, was not a hindrance.[38]

The bill enacted by the Virginia Assembly in 1779 provided only that a road be located and traced, but the two commissioners who performed the work exceeded expectations. On December 1, 1781, when John Kinkead petitioned the Assembly for payment he stated [sic]:

“… although dangerous and Difficult as the Task was, at that Critical Juncture, the business was Completed so that waggons has passd, and has rendered much ease and Expedition to Travelers…”[39]

The date of Kinkead’s application is interesting when taken into consideration with one journey across the Wilderness Road noted by Thomas Speed.[40]

In September 1781, Reverend Lewis Craig brought his entire congregation, numbering 200-600 persons [estimates differ between sources], from Spotsylvania County to Gilbert’s Creek near Stanford, Kentucky. This exodus is documented in various histories of the Baptist Church,[41] but a particularly vivid account is found in George H. Ranck’s The Travelling Church.[42] Curiously, Ranck focuses on the congregants’ wagons. He describes their physical and emotional importance to the pilgrims and depicts a heart-wrenching scene in which they are traded for packhorses at Fort Chiswell. From there, according to Ranck, the beleaguered congregation travelled the remaining 273 miles to Stanford, Kentucky on foot. But, there are at least two problems with Ranck’s account; there is no documented source given for the details of the pilgrims’ journey and the role of their wagons, and his story does not appear to correspond with the known facts.

The 1782 journal of William Brown, written only nine months after Craig’s migration, states that the road from Hanover County [which abuts Spotsylvania County] to the Blockhouse, 100 miles further down the road from Fort Chiswell, was “generally very good.” Furthermore, the 1775 journal of Richard Henderson states that wagons could travel the Wilderness Road to Martin’s Station. Why, then, would this congregation abandon their wagons at Fort Chiswell, 154 miles before necessary? Indeed why, then, would the pilgrims have even begun their journey in wagons loaded down with family heirlooms and possessions that would not be able to cross the mountains into Kentucky? One might suspect that, if in fact they did, it was because in September 1781 they believed they could make the trek to Kentucky in wagons. For the purpose of brevity, a thorough analysis of Ranck’s story is not included here. However, the following information is noted with interest; the History page of the Craigs Baptist Church’s website states that in 1781 its members went to Kentucky in covered wagons. Here, then, is the final question; were these the wagons to which Kinkead referred in his petition on December 1, 1781?

When history is painted with broad brush strokes, fine details can be missed. With regard to documenting the story of the Wilderness Road, a closer examination of primary sources has shown that significant work was done in 1780 to clear the way for wagons to pass. This revelation is not inconsistent with previously held beliefs; it simply adds to the narrative. It is not difficult to understand why the road would require further work in 1792 and 1796. Nature abhors a vacuum. During a period of war, irregular travel, and difficult logistics for maintenance, time certainly quickly conspired with vegetation, falling rocks, and dead tree limbs to render the road yet again impassable. Nonetheless, William McBride’s contribution to the timeline of this important passageway can finally be recognized:

“The road thus located by Captains Kinkead and [McBride], became what was known as the ‘Wilderness Road,’ and for twenty years subsequent thereto was the principal highway traveled by an immense train of emigrants to the West.”[43]

Epilogue

William McBride never petitioned the Virginia Assembly for compensation as the commissioner from Kentucky County for the construction of the Wilderness Road. He had every intention of accompanying John Kinkead to Richmond in December 1781 but fell ill in Rockbridge County and did not recover until after the Assembly had met.[44] McBride planned to return the following fall but was killed leading the Harrodsburg militia across the Licking River at the Battle of Blue Licks on August 19, 1782.[45] Thirty years later, on January 24, 1812, the Kentucky Legislature awarded the heirs of William McBride, his sons William (Jr.) and Lapsley, 2,800 acres of land in consideration of their father’s service in opening the Cumberland Road from Holston to the Crab Orchard.[46]

About the Author:

Mildred likes to dig. For the past eight years, she’s been unearthing information and sifting through facts about her Scotch-Irish heritage and then turning the gems she’s uncovered into magazine articles and soon a creative nonfiction novel. A native Missourian, who now lives in Virginia, Mildred enjoys learning about her people’s history, but more than anything, she loves figuring out how (and why) those people made that history. It’s that backstory that brings the history to life.

Sources

Augusta County Judgments A: November 1764, [Estate of] Halbert McClure vs. James McBride, photocopies of original documents provided to the author by the Augusta County (Virginia) Genealogical Society.

Bruce, H. Addington. Daniel Boone and the Wilderness Road. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1910.

Burgess, Louis A., Ed. Virginia Soldiers of 1776, vol. 3, database on-line: Provo, Utah, Ancestry.com, originally published: Richmond, Va., 1927-29, reprinted for Clearfield Company by Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., Baltimore, Md., 1994.

Chalkley, Lyman. Chronicles of the Scotch Irish Settlement in Virginia, vol. 2, database on-line, Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com, originally published: Rosslyn, Va., 1912-13.

Collins, Richard H. History of Kentucky, vol. 2, Covington, Ky.: Collins & Co., 1874.

Draper, Lyman C., ed. Ted Franklin Belue. The Life of Daniel Boone. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books, 1998.

Genealogies of Kentucky Families from the Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, vol. 1, database on-line, Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com.

Henderson, Archibald. The Conquest of the Old Southwest. New York: Century Co., 1920.

Hening, William Waller. The Statutes at Large; Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, from the first session of the Legislature in the year 1619, 13 vols. (Richmond, Philadelphia, and New York, 1809-1823), vagenweb.org.

A History of Roads in Virginia: “The Most Convenient Wayes.” Richmond, Va.: Virginia Department of Transportation, 2006.

Hulbert, Archer Butler, Boone’s Wilderness Road. Cleveland, Oh.: Arthur H. Clark Company. 1903.

James, James Alton, Ed. George Rogers Clark Papers 1781 – 1784. Springfield, Il.: Illinois State Historical Library, 1926.

Kentucky Doomsday Book. Kentucky Secretary of State, Land Office website.

Krakow, Jere L. Location of the Wilderness Road at Cumberland Gap National Historic Park. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, August 1987.

Pension Application of Charles Bickley, September 8, 1836, Russell County, Virginia. U.S. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, 1800-1900. Database on-line, Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com, 2010.

Petition for the establishment of a town at the falls of the Ohio River. June 8, 1780. Legislative Petitions of the General Assembly, 1776-1865, Library of Virginia, Accession Number 36121, Box 287, Folder 13.

Petition of John Kinkeade, Washington County, Virginia, December 21, 1781, Legislative Petitions of the General Assembly, 1776-1865, Digital Collections, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va., Record No. 000300699.

Pusey, Wm. Allen, A.M., M.D. The Wilderness Road to Kentucky. New York: George H. Doran Company. 1921.

Ranck, George. The Travelling Church. Louisville, Ky.: Filson Club, 1910.

Reverend John D. Shane Interview with William McBride, Lyman C. Draper Manuscript Collection. State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Division of Archives and Manuscripts, Series CC: Kentucky Papers, vol. 9-12, 257-263.

Semple, Robert B. A History of the Rise and Progress of the Baptists in Virginia. Richmond, Va.: Pitt & Dickinson, Publishers, 1894.

Smith, W. T. A Complete Index to the Names of Persons, Places and Subjects Mentioned in Littell’s Laws of Kentucky. Lexington, Ky.: Bradford Club Press, 1931.

Speed, Thomas. The Wilderness Road, a Description of the Routes of Travel by which the Pioneers and Early Settlers First Came to Kentucky. Louisville, Ky.; John P. Morton & Co., 1888.

Spencer, J. H. A History of Kentucky Baptists, vol. 1. Cincinnati, Oh.: J. H. Spencer, 1885.

Sumners, Lewis Preston, History of Southwest Virginia 1746 – 1786, Washington County 1777 – 1870. Richmond, Va.: J. L. Hill Printing Company, 1903.

Swem, Earl G. Work on the Cumberland Road. The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, vol. 1, no. 1, June 1915, 120-121.

Taylor, James B. Lives of Virginia Baptist Ministers. Richmond, Va.: Vale & Wyatt, 1838.

Taylor, John, ed. Chester Raymond Young. Baptists on the American Frontier: A History of Ten Baptist Churches. Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1996.

Todd, Chapman C. The Early Courts of Kentucky. Register of Kentucky State Historical Society, vol. 3, no. 9. Kentucky Historical Society, September 1905. JSTOR (23366218).

Toner, J. M., M.D., Ed. Journal of Colonel George Washington. Albany, N.Y.: Joel Munsell’s Sons, Publishers, 1893.

Verhoeff, Mary. The Kentucky Mountains: Transportation and Commerce 1750 – 1911. vol. 1. Louisville, Ky.: John P. Morton & Company, 1911.

Virginia Apprentices, 1623-1800. Database on-line, Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com, 1997.

Notes

[1] Mary Verhoeff, The Kentucky Mountains: Transportation and Commerce 1750 – 1911, vol. 1 (Louisville, Ky.: John P. Morton & Company, 1911), 81-82. According to Verhoeff and others, the Wilderness Road forked near the Rockcastle River. Boone’s Trace continued north toward Lexington and Benjamin Logan blazed a northwesterly trail past Crab Orchard toward the Falls of the Ohio [Louisville]. The Crab Orchard trail became the preferred branch of the Wilderness Road.

[2] Thomas Speed, The Wilderness Road, a Description of the Routes of Travel by which the Pioneers and Early Settlers First Came to Kentucky. (Louisville, Ky.; John P. Morton & Co., 1888), 29.

[3] Archer Butler Hulbert, Boone’s Wilderness Road (Cleveland, Oh.: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1903), 194 and Verhoeff, The Kentucky Mountains, 83-110.

[4] William McBride and his family were residents of Fort Harrod from 1779 to 1781. They then moved out to McBride’s Station, five miles southeast of Harrodsburg. John Kinkead’s son, Archibald, married William McBride’s niece, Priscilla McBride, in Woodford County, Kentucky in 1792. – Author.

[5] William Waller Hening, The Statutes at Large; Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, from the first session of the Legislature in the year 1619, vol. 10, ch. 12 (Richmond, Philadelphia, and New York, 1809-1823), 143-144. Vagenweb.org, accessed March 17, 2016.

[6] Lewis Preston Summers, History of Southwest Virginia 1746 – 1786, Washington County 1777 – 1870. (Richmond, Va.: J. L. Hill Printing Company, 1903), 279-283. Sumners states that Boone’s Trace had been improved by 1781.

[7] Lyman C. Draper. The Life of Daniel Boone. Ed. Ted Franklin Belue (Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books, 1998), 558. Calloway was killed near Boonesborough on March 8, 1780.

[8] Reverend John D. Shane Interview with William McBride, Lyman C. Draper Manuscript Collection. State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Division of Archives and Manuscripts, Series CC: Kentucky Papers, vol. 9-12, 257-263. (Hereafter William McBride Interview, DC).

[9] Kentucky Doomsday Book, 39-40. Kentucky Secretary of State, Land Office website, accessed July 9, 2011. (Hereafter Kentucky Doomsday Book). In 1781, William McBride built McBride’s Station on his claim.

[10] William McBride Interview, DC.

[11] Kentucky Doomsday Book.

[12] Virginia Apprentices, 1623-1800 (database on-line, Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com, 1997, original data: March 17, 1768, Augusta Parish Vestry Book 1746-1780, 397).

[13] Petition for the establishment of a town at the falls of the Ohio River. June 8, 1780. Legislative Petitions of the General Assembly, 1776-1865, Library of Virginia, Accession Number 36121, Box 287, Folder 13.

[14] Genealogies of Kentucky Families from the Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, vol. 1, (database on-line, Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com), 323-324.

[15] Richard H. Collins, History of Kentucky, vol. 2, (Covington, Ky.: Collins & Co., 1874), 476.

[16] James Alton James, Ed. George Rogers Clark Papers 1781 – 1784. (Springfield, Il.: Illinois State Historical Library, 1926), 346. Also, George Rogers Clark Papers, Library of Virginia, microfilm roll 9, 15359 – 15757.

[17] Earl G. Swem, Notes on the Cumberland Road. The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, vol. 1, no. 1, (June 1915), 121, and William McBride Interview, DC.

[18] Speed, The Wilderness Road, 30.

[19] Louis A. Burgess, Ed. Virginia Solders of 1776 (database on-line, Provo: Utah, Ancestry.com, originally published Richmond, Virginia, 1927-29), 1272.

[20] Lyman Chalkey, Chronicles of the Scotch Irish Settlement in Virginia, vol. 2, (database on-line, Provo: Utah, Ancestry.com, originally published: Rosslyn, Virginia, 1912-13), 277.

[21] Augusta County Judgments A: November 1764, photocopies of original documents provided to the author by the Augusta County (Virginia) Genealogical Society. On December 6, 1762, James McBride, the brother of William McBride, signed a promissory note for £5 to Halbert McClure. This debt was in litigation for the next two years.

[22] Pension Application of Charles Bickley, September 8, 1836, Russell County, Virginia. U.S. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, 1800-1900 (database on-line, Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com, 2010, original data: Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15. National Archives, Washington, D.C.).

[23] Swem, Notes on the Cumberland Road.

[24] Jere L. Krakow, Location of the Wilderness Road at Cumberland Gap National Historic Park. (U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, August 1987), Appendix C: Bill for Services and Supplies in Road Building over Cumberland Mountain, April 20, 1781, 88-91.

[25] As previously noted, William McBride was a master blacksmith. – Author.

[26] Specifically, 47% of the expenditures were for packhorses, and 31% for foodstuff (beeves, salt, and flour). – Author

[27] This calculation assumes that the crew worked for 92 days (July 1 – October 1) on the 165-mile stretch from the Blockhouse (Gate City, Virginia) to Crab Orchard, Kentucky.

[28] Present-day Cumberland, Maryland.

[29] Fort Necessity.

[30] The Nemacolin Trail.

[31] J. M. Toner, M.D., Ed. Journal of Colonel George Washington [1754 – 1755]. (Albany, N.Y.: Joel Munsell’s Sons, Publishers, 1893), 42-74. Washington’s journal indicates that he arrived at the Great Meadows on May 24th. It is assumed, in this calculation, that he left Will’s Creek on April 25th and that the distance traversed was 52 miles.

[32] Hulbert, Boone’s Wilderness Road, pp. 101-107. Hulbert also reproduces a second journal dated 1775, William Calk’s, 107-117, which provides an experiential look at life on the Wilderness Trail but does not give any indication of the speed of travel or road conditions.

[33] For the purpose of comparison, the following locations were used to calculate distances: the Blockhouse/Gate City, Va., Wallen Ridge/Stickleyville, Va., Martin’s Station/Rose Hill, Va., Yellow Creek/Middlesboro, Ky., Cumberland River/Pineville, Ky., Richland Creek/Barbourville, Ky., Laurel River/London, Ky., Dicks [Dix] River/Brodhead, Ky. – Author

[34] Only days upon which travel was recorded were used for this calculation. Days spent in camp were not considered “travel-days.” – Author

[35] Historians state that the two branches of the Wilderness Road forked at the Rockcastle River. However, both Henderson’s and Brown’s journals refer to a camp at the head of the Dix River, 25 miles beyond the Rockcastle River. – Author

[36] Speed, The Wilderness Road, 17-20.

[37] Hulbert, Boone’s Wilderness Road, 123. The assumption has been made that all seven days of Brown’s journey were travel-days.

[38] Wm. Allen Pusey, A.M., M.D. The Wilderness Road to Kentucky. (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1921), 14.

[39] Petition of John Kinkeade, Washington County, Virginia, December 1, 1781. Legislative Petitions of the General Assembly, Digital Collections, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va., Record No. 000300699. Accessed 2/21/16.

[40] Speed, The Wilderness Road, 39-40.

[41] J. H. Spencer, A History of Kentucky Baptists, vol. 1 (Cincinnati, Oh.: Printed for the author), 1886, 25-32; Robert Baylor Semple, History of the Baptists in Virginia. (1810) revised and extended by G. W. Beale, 1894. (Paris, Ar.: The Baptist Standard Bearer, Inc., 2005), 200, 472-473.; James B.Taylor, Lives of Virginia Baptist Ministers. (Richmond, Va.: Vale & Wyatt, 1838), 84-88; John Taylor, Baptists on the American Frontier: A History of Ten Baptist Churches. (1823), third edition, ed. Chester Raymond Young. (Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1996), 41-44. These sources note the occurrence of the pilgrimage, but do not detail the actual travel experience.

[42] George Ranck, The Travelling Church. (Louisville, Ky.: Filson Club), 1910. 12-30.

[43] Sumners, History of Southwest Virginia, 280.

[44] William McBride Interview, DC.

[45] Collins, History of Kentucky, vol. 2, 663. Lewis Rose shot an Indian in the act of scalping Captain William McBride.

[46] W. T. Smith, A Complete Index to the Names of Persons, Places and Subjects Mentioned in Littell’s Laws of Kentucky. (Lexington, Ky.: The Bradford Club Press, 1931), 128-129. (Littell, Volume 4, page 330). archive.org, downloaded February 18, 2016).

After realizing what occurred free sample just need to think that the that nil wish alter.

James H McBride

I found Miss Mildred Armao’s depictions of my 4x grandfather, William McBride accurate per my family’s legend of Capt McBride.

I would be interested how Miss Armao picked William McBride to research and I would be most interested in communicating with her.

Mildred Leedy Armao

Thank you for your comment, Mr. McBride. Captain William McBride is my 4th great grandfather as well! You can contact me at McBrideResearch@gmail.com. I look forward to hearing from you.

Richard Hileman

A very interesting contribution to the literature on the Wilderness Road. Many of my ancestors took the road, including my 4great grandparents Joseph and Ann Lee Hanks, with their unmarried daughter, Lucy, and her infant daughter, Nancy, who became the mother of Abraham Lincoln. They made the journey in 1784 or 5, so could have had a wagon it looks like.

Mildred Leedy Armao

Thank you for your comment! The history of Kentucky and its people is fascinating! I’m so glad you found the article interesting.

karen gay willard

looking for any info about ancestors in Cumberland gap anytime from 1792 until present

Redwine

Martin

Combs

Bishop

thank you,

Karen Redwine Willard 513398 2686

karenwillard48@yahoo.com

Rogers Barde

I was very interested in your article and regret that I didn’t read it earlier. My Scots-Irish ancestors came to KY in 1781 and I love thinking they could have come in wagons! Your research is very important and I appreciate it.

My ancestors were Rodgers, Caldwell and half brothers Mitchell, and Irvine. They settled in the Danville area.