By Kandie Adkinson, Administrative Specialist, Land Office Division, Office of the Secretary of State

The Third in a Series of Articles Regarding the Significance of Tax List Research

As the great-great-granddaughter of a Virginian who fell during Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg and the widow of a former commander of the Sons of Union Veterans, Department of Kentucky, I looked forward to our sesquicentennial remembrance of the Civil War. Starting in 2011 we saw a marked increase in the number of reenactments, books, debates, and visual media regarding the war that divided our families and our country.

As the great-great-granddaughter of a Virginian who fell during Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg and the widow of a former commander of the Sons of Union Veterans, Department of Kentucky, I looked forward to our sesquicentennial remembrance of the Civil War. Starting in 2011 we saw a marked increase in the number of reenactments, books, debates, and visual media regarding the war that divided our families and our country.

How many times have we heard that Kentuckians lost their land and left the commonwealth because they supported the “wrong side” during the Civil War? In truth, the land may have been lost by the owner for nonpayment of taxes. Money had been borrowed by the government to recruit and arm the troops; the war debt had to be paid. Taxes were the primary source of governmental revenue in the 1860s just as they are today.

In this article we will examine the tax laws of Kentucky from 1861 through 1865. Admittedly, the subject of taxpayers and revenue collection may not be as interesting as Civil War battles and skirmishes, but without a doubt, the number of reenactors recreating this topic number in the millions–every 15 April when taxes are due.

Selected Excerpts from Kentucky Legislation Regarding the Tax Process

Note: These and other acts pertaining to the collection of the “Permanent Revenue” and county levies, as well as codified statutes and regulations, may be researched in their entirety by visiting the Kentucky Supreme Court Law Library, the Thomas D. Clark Center for Kentucky History Research Library, or the Kentucky Department for Libraries & Archives research room, all in Frankfort, Kentucky. Legislation described in this article is provided for historical research purposes. Check the Kentucky Revised Statutes for current laws affecting taxation.

1861 (26 March)

Upon conviction on indictment by the county grand jury, any county court clerk who failed, for one month after the passage of this legislative act, to transmit to the Auditor of Public Accounts a copy of the commissioner’s book for his county for the year 1860, was ordered to be imprisoned thirty days in the county jail and fined from $500 to $1000 at the discretion of the jury. This law affected commissioners’ books that had been completed in 1860 and in the clerk’s control. Upon conviction of the clerk, the county judge was named the responsible party for ensuring the commissioners’ tax book was sent to the state auditor’s office.[1]

1861 (25 September)

An act to amend an act entitled “An act for the regulation of the militia, and to provide for the arming of the State,” approved 24 May 1861; and also to provide further for the public defense.

Whereas, The hostilities which threatened the peace of the State at the time the act to which this is an amendment was passed, have been followed up by the wanton and unjustifiable invasion of Kentucky by the armed forces of the so-called Confederate States, and war has thus been forced upon the good people of the State; wherefore it becomes the solemn duty of this Legislature, without delay, to provide means for the public defense; therefore, Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky:

The following are summaries of sub-sections.

- The Board of Commissioners created in the original legislative act was authorized to apply borrowed funds to the defense of the state at their discretion;

- The Board of Commissioners was authorized and empowered to borrow, on the credit of the state, the additional sum of one million dollars for the defense of the state;

- The Board of Commissioners was authorized to procure loans from any incorporated or private bank, or from any other moneyed institution, or from individuals in or out of Kentucky. Bonds, executed by the governor, were issued to lenders; the bonds were payable at such time and place as agreed, not less than ten years from the date of issuance, at a rate of six per centum per annum, the interest to fall due semiannually.

- For the purpose of providing means of paying the debts created by the state under this act, an additional tax, in aid of the sinking fund, was directed to commence in 1862. The tax was an additional five cents upon each $100 of value of the real and personal estate directed by law to be assessed for taxation, paid annually by the persons assessed. The tax was to be collected and paid into the public treasury in the same manner as the other revenue of the state was collected and paid.

- Peter Dudley, Samuel Gill, George T. Wood, Edmund H. Taylor, and John B. Temple were appointed to serve as the Board of Commissioners.

- The act was effective from and after passage.[2]

1861 (30 September)

The “several” sheriffs and the late sheriffs and their sureties who had judgments against them in fiscal court “for the collection of the public revenue” in their respective counties, were permitted to pay the amount of their judgments, interest, and costs in quarterly installments within one year of the date of the act. Each sheriff and surety had to post bond “with good personal security” stipulating the “faithful payment of the installments and the interest thereon” to be paid into the public treasury. This act did not apply to sheriffs and securities for whose benefit special acts had been passed by the General Assembly.[3]

1861 (3 October)

Sheriffs and collectors of the revenue for the year 1861 were granted additional time to return their listings of delinquent taxpayers; however, the extension to the January term of 1862 was not a justification for delaying the speedy collection of taxes.[4]

1861 (16 December)

When taking the lists of taxable property, tax assessors could refer to and be governed by the lists of taxable property from the preceding year when determining the kind of property and amount of value owned by taxpayers absent in the service of the Federal or Confederate authorities. Property destroyed or lost since the lists were taken did not have to be listed or estimated. The act was effective from and after the 10th day of January 1862.[5]

1861 (21 December)

If any county failed to assess taxes or if any county failed to return their tax book to the Auditor of Public Accounts, as required by law, the taxes due by the taxpayers would be assessed, collected, and paid based on the tax book submitted to the auditor’s office the previous year. The auditor was required to “give notice” the prior year’s book was being used in an announcement in one of the newspapers published at the seat of government. Further, the commonwealth was authorized to place a lien on the assessed property. The sheriff or collector of tax was given the power and authority to collect the taxes, as in other collection of the public revenue.[6]

The Civil Code of Practice was amended to state if any sheriff, clerk, or collector of the revenue failed to pay the received moneys as required, motions against the defaulting officers could be filed in the Franklin Circuit Court without notice to the debtor or his sureties.[7]

1862 (25 February)

The General Assembly ordered the sheriff or collector (of taxes) to proceed with tax collection immediately after 1 June each year. Between 1 September and 15 October, each year, the sheriff or tax collector was required to spend two days in each of the election districts in the county to receive unpaid taxes. It was the duty of the taxpayers “to attend at the times and places designated by the sheriff and pay the taxes due.” Notice of the time and place fixed by the sheriff for his attendance in said districts was to be posted on the courthouse door and some public place within the district, at least thirty days prior to the designated time. If the taxpayer failed to pay his taxes before 15 October, he had until 15 December to pay the taxes to the sheriff or tax collector of his county of residence. If the taxes were not paid before 15 December, an additional 10% of the tax due was added to the bill. The penalty was collected by the sheriff or collector and was retained by them in addition to their commissions. The sheriff or collector was ordered to make a sworn oath at the July, September, and November terms of the county court of the amount of revenue collected that was due the commonwealth. The statement was filed by an order of the court and a copy transmitted by the clerk to the Auditor of Public Accounts. Immediately after making each statement, the sheriff or collector was ordered to pay into the public treasury the revenue he had collected after deducting his commission. “Nothing in this act shall be construed to excuse the sheriff or collector from the duty of paying into the public treasury the whole amount of the public revenue due from his county, as now required by law.”[8]

“In all cases where, by reason of the invasion of this State by the so-called Confederate troops, or those acting in concert with them, sheriffs have failed or been prevented from executing the bond required by law for the collection of the revenue, the further time until the March or April terms of the county courts is given them for the execution of such bonds. If any sheriff shall fail against the time herein fixed to execute such bond, the county court shall declare his office vacant, and proceed to appoint his successor.” The act was effective from and after its passage.[9]

1862 (28 February)

Apparently many Kentuckians had failed to list their property with the tax assessor or the county court for several years and, in many instances, sheriffs had collected delinquent taxes but had failed to submit their reports or “accounts.” To remedy the situation the General Assembly ordered:

- The Auditor of Public Accounts to appoint one or more agents for the ensuing two years to carry out the provisions of this act.

- The agents were ordered to provide the county courts with listings of property owners who had failed, since 10 January 1856, to report their properties to the assessor, supervisor of tax, county court clerk, or sheriff. The court was ordered to issue a summons against the persons, requiring them to appear before court in thirty days after the summons was served. The taxpayers had to list their property for taxation for the years they had failed to do so. The court then fixed the value of the delinquent taxes.

- If the sheriff defaulted in his duties after collecting the back taxes, the auditor’s agents were ordered to inform the county court. A summons would order the sheriff and his sureties to appear before the court in ten days and explain why a judgment should not be rendered against him for the sum of money owed the commonwealth. If it was proven to the court’s satisfaction that the money was collected and not accounted for, the sheriff and his sureties were subject to a judgment including 50 percent damage and the cost of the proceeding.

- To enable the auditor’s agents to obtain information regarding the listing of property and tax collections since 10 January 1856, they were authorized to inspect county poll-books, the assessor’s books, all records regarding tax collection, and the census returns in the office of the Secretary of State. (Note: Apparently the records were removed from the office of the Secretary of State prior to records retention and transmittal schedules.)

- The auditor’s agents were entitled to a quarterly payment of one-third of all amounts certified by the said county court to the auditor and paid into the treasury.

- The commonwealth was not liable for any costs incurred upon failure to obtain a judgment against delinquent sheriffs, collectors, or taxpayers.

- The agents were authorized to investigate the accounts of county clerks, circuit courts, quarterly judges of the commonwealth, and justices of the peace of Jefferson County and Louisville to determine what, if any, sums of money had been received but not paid as required by law. The agents were instructed to institute proceedings as necessary.

- Before they assumed their duties, agents of the auditor were required to take an oath that they supported the Constitution of the United States, that they had not aided or abetted the rebellion, and they were opposed to the overthrow of the Union.

- This act was effective from its passage.[10]

1862 (8 March)

In any county where the copy of the tax commissioners’ book was placed in the hands of the sheriff for the collection of the revenue then taken from him by any person or persons acting under the authority of the Provisional Government of Kentucky, or the “Confederate States of America,” the county clerk was ordered to furnish the sheriff another copy of the said book for which said clerk was to receive the same fee he was allowed for similar services. The Auditor of Public Accounts was directed to make a copy of the commissioners’ book for any county, and forward the copy to the county court clerk upon proof that the original book was destroyed or carried off by persons claiming to act under the authority of the so-called “Confederate States of America”, the “Provisional Government of Kentucky,” or any person or persons acting without legal authority. The person making the copy was entitled to the same pay as allowed clerks for similar services. The act was effective from the date of its approval.[11] Note: The preceding act, Chapter 457, benefited the common school districts that were “broken up and unable to be taught out” during the “troubled condition of the country during the latter part of the past year.” Chapter 480 details an act benefiting soldiers in the armies of Kentucky and the United States with outstanding bonds and recognizances.

1862 (11 March)

It was reported to the General Assembly that William J. Fields, Carter County sheriff, had vacated his office “by leaving the county, joining in the rebellion against the government, and by failing to discharge his duties as sheriff in the collection of the public revenue.” The General Assembly ordered the Carter County Court to appoint a tax collector during its March, April, or May 1862 court term. Nothing in the legislation exempted William J. Fields and the sureties in his official bond as sheriff or collector from the liabilities imposed by law.[12] Note: Similar legislation is recorded in Chapter 521 regarding M. H. Dickinson, Barren County, who had vacated the office of sheriff to join the rebellion, leaving a portion of the public revenue due by Barren County for the year 1861 uncollected. Other legislation extended the time period for collecting taxes in specific counties such as Muhlenberg, Green, Boone, and Morgan.

1862 (11 March)

This act directed tax assessors in 1863 to take a listing of the number and value of sheep killed by dogs in their respective counties from January 1, 1862, to the time of taking the lists of taxable property, and to include the information in the commissioners’ book.[13] Note: The following act titled “Chapter 509” declared any Kentuckian who shall enter or who had already entered the service of the “so-called Confederate States” in a civil or military capacity, or into the service of the “so-called Provisional Government of Kentucky” in a civil or military capacity and who continued in such service after this act took effect, or shall take up or continue in arms against the military forces of the United States or the State of Kentucky, or shall give voluntary aid and assistance to those in arms against said forces, “shall be deemed to have expatriated himself, and shall no longer be a citizen of Kentucky, nor shall he again be a citizen, except by permission of the Legislature, by a general or special statute.” Any person who attempted, or was called on to exercise any constitutional or legal right and privilege of a citizen of Kentucky could be required “to negative on oath the expatriation provided in this act”; and upon failure or refusal to do so, would be denied to exercise the right or privilege. The act was effective thirty days from and after its passage. The legislation passed and became law, the objections of the Governor “notwithstanding.”

1862 (14 March)

Commencing with the assessment for 1862, an additional tax of five cents upon each hundred dollars of the value of real and personal estate subject to revenue taxation was ordered to be collected. Proceeds were to be applied to the “ordinary expenses of the Government.”[14]

1862 (15 March)

An Act authorizing proceedings against the Governor, members of the Council, and other officers of the so-called Provisional Government, for the recovery of the public revenue seized by them, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky:

The following are summaries of sub-sections.

- The governor and council were ordered to refund and pay into the treasury of the commonwealth all the public revenues belonging to the state “seized upon, collected, or in anywise appropriated to their use, or the use of the said Provisional Government, by themselves or by their orders, or by anyone acting under their pretended authority”; the said governor and council were bound to answer, personally, out of their own estate, for the said revenue.

- All persons who had claimed to act as sheriffs, auditors, commissioners, treasurers, or other inferior officers or agents, and their sureties, if any, under the pretended authority of the said Provisional Government, were declared liable for all public revenue of the state which at any time may have been in their hands or under their control. They, too, were bound to answer personally, out of their own estate, for such revenue.

- The Franklin Circuit Court was assigned the responsibility of recovering the demands and enforcing the liabilities. The proceedings were in the name of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, by petition, in one or more actions against all the persons composing the Provisional Government, and their officers and agents, or against any one or more of them.

- Upon the filing of the petition in the Franklin Circuit Court, the clerk was ordered to issue a summons against the defendant or defendants to answer; and also an attachment against the estate of the defendant or defendants for the sum or sums claimed in the petition and an additional sum of $500 to cover court costs.

- It was sufficient for the petition to state that the defendant or defendants, without lawful authority, “seized upon, collected, appropriated, or had in his custody” the public revenue of the commonwealth and the amount sought to be recovered. Affidavits were not required.

- The summons and attachment could be sent to any county, or to the several counties in the state, but a return that the defendant or defendants could not be found upon a summons issued to the county of Warren, where it was represented the said Provisional Government was then located, was deemed sufficient service on the defendant or defendants for the purposes of the action. Provided: That publication, for at least thirty days of the pendency of the action, was printed in the Louisville Journal and Democrat.

- The summons and attachment could be directed to and served by the sheriff, coroner, or jailer of any county in the state or by any agent appointed by the Auditor of Public Accounts.

- No motion could be made to vacate or modify the attachment except on the final trial of the action.

- The commonwealth, from the time the act took effect, had a lien upon all the estate of each and all defendants against who judgments may be recovered under this act, for the satisfaction of the judgment, interest, and costs.

- The General Assembly assigned the duty of “setting on foot” the prosecution of these actions to the auditor, treasurer, and attorney General. It was the duty of the county judges, sheriffs, clerks, and other civil officers to furnish the auditor all information regarding the seizure, collection, or appropriation of the public revenue in their respective counties by the said Provisional Government or those acting under its authority.

- Nothing in this act released any sheriff, or other officer entrusted with the custody or collection of public revenue, or the taxpayer from responsibility in consequence of having paid their taxes to the Provisional Government or its “pretended officers or agent.”

- This act was effective from and after its passage.[15] Note: The following act in Chapter 565 is entitled “An act to amend an act for the regulation of the militia and to provide for arming this State, approved May 24, 1861, and an act entitled “An Act to provide for the public defense” approved September 25, 1861.” The amending legislation reorganized the Military Board and appointed John B. Temple, President, and George T. Wood, Associate. The board had power to make necessary provisions for the protection and comfort of the sick and disabled soldiers and officers of the several regiments, battalions, and batteries of Kentucky volunteers not fully provided for and cared for by the United States. The board was given the power to employ sanitary agents, physicians, nurses, etc., to establish and maintain hospitals, and to use and employ such means and agencies as necessary for those purposes. The board was charged with the duty of making, by themselves, or agents, all settlements with the general government for sums expended by the State of Kentucky through the Military Board, Adjutant General, Quartermaster General, or other accounting or distributing officer and to proceed with such settlements “with all convenient dispatch.”

1862 (15 March)

For those counties in which the sheriff had failed to execute the bond required by law for the collection of the public revenue or for the county levy for the years 1861 and 1862, or either, and no collector had been appointed in his stead, or if the sheriff had posted bond and abandoned the state or otherwise vacated his office, and no sheriff or collector had been appointed, the General Assembly assigned the duty of appointing a tax collector to the county court. The appointment was ordered to be made by July 1862. If any sheriff or collector had failed to make a return of his lists of delinquents for 1861, he was allowed a filing extension to1 July 1862.[16] Note: County levies are discussed in the following chapter.

1863 (17 January)

The General Assembly had been advised that many county officers elected on the first Monday in August 1862, were prevented from taking the oath of office, and entering upon the discharge of their duties at the time fixed by law, “on account of the occupancy of the State by the rebels.” This act declared all legal acts done by said officers, who had since qualified or were hereafter qualified, in force and effect as if the officers had qualified at the time fixed by law. This act was in force from its passage.[17]

1863 (20 January)

The governor was given the power to remit damages against any defaulting sheriff, clerk, or other person authorized to receive or collect money, revenue, or tax after the principal of the judgment, with interests and costs, had been paid into the public treasury. The act was effective for one year after passage.[18]

Sheriffs and collectors of the public revenue and county levies were allowed additional time to make out and return their delinquent lists for the year 1862. The new deadline was April 1, 1863.[19]

1863 (4 February)

Sheriffs and other collecting officers were permitted to submit their listings of 1861 delinquent taxpayers to the auditor’s office any time before 1 April 1863. The county court could receive, examine, and certify said delinquent lists without the presence of the justices of the peace, as required by law; or the said justices could be summoned to attend and aid the county judge in the reception and examination of said lists.[20]

1863 (4 February)

An act providing for the collection of the tax upon the Enrolled Militia for the year 1862.

The General Assembly authorized the various collectors of the public revenue for the year 1862 to return to the auditor’s office, as delinquents, all those who had failed to pay for that year the tax of fifty cents assessed upon the enrolled militia of the state, under the act, entitled “An act to re-enact the State Guard Law, with sundry amendments, and to organize the militia of the State”. The list of delinquents, thus returned, was ordered to be relisted by the Auditor of Public Accounts with the sheriffs and other collecting officers of the public revenue for the year 1863. It was the duty of the sheriffs and other collecting officers to receive and to collect said lists in the same manner they were required to receive and collect delinquent lists in the collection of the general revenue of the state. If the officers charged with the collection of said tax for the year 1862 failed or refused to return their lists of delinquents by the first day of April 1863, it became the duty of the auditor to “compel such defaulting officer to account for and pay said tax for his county into the public treasury, for the use of the fund to which it belonged.” The legislature ordered the Auditor of Public Accounts to furnish the sheriffs and other collecting officers for the years 1862 and 1863 a copy of this act, which was in effect from and after its passage.[21]

1863 (28 February)

Taxpayers who had failed to pay his or her taxes before the fifteenth day of October in a county where the courthouse was occupied by troops, or undergoing repairs, or for any other reason rendering the courthouse unavailable, were directed to pay their taxes at the office of the sheriff or tax collector in the town in which the courthouse was located by 15 December. If any taxpayer failed to pay the tax before that date, a 10 percent penalty was added to the amount of the unpaid tax. The total due was collected by the sheriff or collector; the penalty was retained by the sheriff or collector in addition to his commission.[22]

1863 (2 March)

The time allowed for the appointment of collectors of the public revenue and county levy for the years 1861 and 1862 was extended to 1 July 1863.[23]

1863 (3 March)

The General Assembly authorized sheriffs, or other collecting officers of the public revenue or county levy, to attach any choses[24]in action or debts due to said tax payer within the county if the taxpayer had failed or refused to pay the revenue tax or county levy due by him or is insolvent. The sheriff or collecting officer was ordered to give the person a written notice of the attachment. The document warned the individual to appear before the presiding judge of the county, at his office, on a day to be fixed by the sheriff or collecting office, not less than ten days after the service of the notice, to answer as garnishee. If the judge sustained the attachment, he was directed to give the sheriff or collecting officer a written order to collect said taxes out of the estate of the person in whose hands the same were attached. The sheriff or collecting officer was allowed a fee of $0.25, to be paid by the taxpayer, for serving the notice. [25]

1863 (21 December)

The General Assembly exempted the citizens of Clinton County from the payment of the annual tax or revenue due the state for the years 1862 and 1863.[26]

1864 (23 January)

This act further amended an act to amend the Revenue Laws approved 28 February 1862. The agent of the Auditor of Public Accounts was now authorized to investigate incorporated companies, cities, railroads, water works, gaslight, and other entities from which rents, tolls, or any other income was collected to ensure taxes were being paid. The agent was also ordered to investigate the collection of the military tax and to proceed with litigation against the sheriff, by motion or otherwise, in the Franklin Circuit Court, or in the circuit court of the county in which the sheriff was located to recover the amount found due the commonwealth. The accounts of clerks, judges, marshals of police courts, the Secretary of State, the Clerk of the Court of Appeals, and the Register of the Land Office were also ordered to be investigated. The agent was directed to collect unpaid jury fees due the state. The agent was granted access to all records deemed necessary for his investigation. Subsection seven states: “That in view of the difficulties that have attended the discharge of the duties required by law of the agent or agents of the Auditor, growing out of the state of war that has overrun all the southern portion of the State, and the absence from the State of (many in the Southern Confederacy and some in the Union army) a large number of those whose accounts it was the duty of the said agent to investigate, therefore, Thomas S. Hayden, the present agent of the Auditor, is hereby allowed further time necessary to discharge the duties required by law of the agent of the Auditor, and close up the business.” This act was in effect from and after its passage.[27]

1864 (9 February)

An Act for the Benefit of Monroe County.

Whereas, it satisfactorily appears to the legislature of Kentucky that the county of Monroe has been severely visited by the outrages and ravages of this wicked rebellion; many of her citizens have been robbed, impoverished and ruined; many driven from their families and homes, and many others massacred and murdered; her courthouse, clerks’ offices and public buildings, together with all the records and papers, have been fired and consumed; yet, in the midst of all her calamities, she has gallantly sustained her country’s flag, and promptly furnished her quota of men in the field—wherefore, Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky: That the revenue of said county, yet to be collected for the years 1863 and 1864, which is collectable and payable into the treasury of this Commonwealth, shall be and the same is hereby set apart and appropriated to aid said county for rebuilding her courthouse and clerks’ offices, consumed as aforesaid. The revenue thus appropriated shall be collected and paid into the treasury under and according to existing laws, and when so paid into the same shall be paid over to the county court of Monroe county, upon its order, or to its legally constituted agent, to be by said court used and appropriated for the purposes aforesaid, and according to law. This act to take effect from its passage.[28]

1864 (18 February)

Whereas, F. L. St. Thomas, John McClintock, James E. Dickey, Samuel Taylor, C. G. Land, Thomas Duval, and Joseph Minor, citizen soldiers of Harrison county, Kentucky, belonging to no military organization, either State or Federal, and therefore entitled to neither pay nor bounty under existing laws, were severely wounded in the fight with John Morgan’s forces at Cynthiana, on the 17th day of July 1862, and in consequence of their wounds incurred great loss of time and heavy expense, therefore, Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky: That the sum of two hundred dollars each be and the same is hereby appropriated to said citizen soldiers and that the Auditor draw his warrant on the Treasurer in their favor for said several sums, to be paid out of any moneys in the treasury not otherwise appropriated. That this act take effect from and after its passage.”[29] Note: Although this legislation does not pertain to revenue collection, it exemplifies acts and resolutions for the benefit of certain individuals that are included in the majority of the volumes of the “Acts of the Kentucky General Assembly.

1864 (22 February)

Properties belonging to any city or town that were necessary for transacting governmental business were declared exempt from taxation. This included police court houses, mayors’ offices, offices for city or town officers in said buildings, fire engine houses, engines and horses belonging thereto, work houses, alms-houses, hospitals, pest-houses, and the grounds belonging thereunto. Excluded were vacant lots or property upon which the city or town received any rent, dividend or income.[30] Note: This legislation was amended 3 June 1865, in Chapter 1697, to release city lots and properties from accrued taxes.

1865 (24 January)

The compensation for tax assessors was increased to 12.5 cents for each list of taxable property. The act was in effect from passage and was directed to be in force for 1865 and 1866.[31]

Proceedings against sheriffs and others to compel the payment of tax revenue could be initiated by the Auditor at the January term of the Franklin Circuit Court each year or any subsequent term of said court whenever “in his opinion, the public interests will justify the postponement to a subsequent tern, provided the Auditor does not postpone the proceedings beyond the second term of the Franklin Circuit Court.”[32]

1865 (31 January)

The tax assessors were directed to “take an account of the number of dogs over six months of age owned or possessed by each person, or kept about any one house.” A tax of $1.00 was ordered to be levied on each dog; the sheriff was ordered to collect and “account for” the taxes in the same manner as other state revenue. Each bona fide housekeeper was allowed to keep two dogs free of tax. The funds arising from the dog tax were for the benefit of the common school fund. The legislation further states that every person owning, having, or keeping any dog shall be liable to the party injured for all damages done by such dog; and it was deemed lawful for any person to kill, or cause to be killed, any dog found roaming at large on his premises without the presence of the owner or keeper of such dog. It was also deemed lawful for any person, at any time, to kill, or cause to be killed, any dog which may have been found killing, worrying, or injuring any sheep or lambs. “And when any person might be sued for killing a dog, and his defense was this legislative act, he shall be a competent witness to prove the same.” The act was effective upon passage. [33]

1865 (3 February)

The compensation to sheriffs for collecting taxes was increased by adjusting their commissions upon the sums collected, accounted for, and paid into the Treasury. The new rates were 10 percent (first thousand); 8 percent (second thousand); 6 percent (third thousand); 5 percent (fourth thousand); and 4 percent on all above four thousand. This legislation was limited to the collection of revenue in 1865 and 1866.[34]

1865 (7 February)

Kentucky taxpayers were directed to pay their taxes to the sheriff of the county seat of their respective counties, or such other place as the sheriff may designate by notice, between 1 June and 15 December each year. The sheriff was mandated to “keep an office at or near the courthouse of his county, and by himself, or deputy, attend at said office every day from 1 June to 1 October to receive the taxes. In Kenton County the sheriff was ordered to keep an office, by himself or deputy, at Independence and Covington; in Campbell County, the sheriff was ordered to keep an office, by himself or deputy, at Alexandria and Newport. The sheriff was authorized to collect an additional 10 percent on the tax due from any taxpayer who failed or refused to pay his taxes. The sheriff could retain the penalty as additional compensation. The sheriff was ordered to post a minimum of three printed public notices in each election precinct in his county, at the most public places in the said precinct, notifying the taxpayers at least thirty days before the tax was due and where they were required to pay the tax. If the sheriff failed to post the notices, he was not allowed the 10 percent on the tax due the taxpayer. The act remained in force for two years from passage.[35] Note: On 3 June 1865, the Kentucky General Assembly repealed this act in relation to the counties of Laurel, Rockcastle, Knox, and Woodford.[36]

1865 (14 February)

Existing laws were amended to permit the county courts to increase the county levy to $2.00 per tithable in any one year. The act was effective immediately.[37]

1865 (3 March)

Among the provisions of this act regarding agents of the auditor, it was declared agents could not receive compensation for their performance. Instead, the agents were permitted to be paid by commissions for all sums, in the aggregate, “they may cause to be paid into the treasury.” Percentages were as follows: On the first $15,000.00, one third; over $15,000.00, and under $30,000.00, 15 percent, and on all over $30,000.00, 10 percent.[38]

1865 (4 March)

Commencing with the assessment for 1865, an additional annual tax of $0.05 per $100 of value of real and personal estate subject to taxation was ordered to be collected.[39]

1865 (25 May)

In separate legislative acts on this date, the General Assembly: (1) legalized the assessments made by Simeon Crawford and his deputies for Grayson County in 1865; (2) granted an extension of two years for E. B. Caldwell, late sheriff of Lincoln County, to collect uncollected taxes and fee bills provided he shall be subject to “all the pains and penalties for collecting illegal taxes and fee bills; and (3) granted a two-year extension for Isaac Radley, late sheriff of Hardin county, to collect all his arrearages of tax and fee bills due him as sheriff.[40]

1865 (27 May)

This act stated earlier legislation, approved March 10, 1856, could not be construed to exempt from taxation any lot or parcel of ground in any city or town, other than church property, on which any private school was taught. The act was in effect from passage. [41]

1865 (31 May)

Chapter 83 of the Kentucky Revised Statutes was amended to state wholesale dealers in playing cards who sold packages of not less than half a gross were no longer required to pay the tax currently required.[42]

1865 (3 June)

Sheriffs were relieved of their duties to collect all uncollected militia fines due under the provisions of the law for 1863 and 1864.[43]

1865 (3 June)

For those counties in which no assessments had been made since 1860, the Auditor of Public Accounts was directed to make up his statements and settlements of revenue from the assessments and books returned for the year 1865. The sheriffs and collectors of revenue for 1865 were ordered to collect all back taxes and account for and pay the same into the public treasury at the same time the revenue of 1865 was due and payable. Provided, That the sheriffs of 1865 executed bond, with good security approved by the county court conditioned for the faithful collection and payment thereon. The same rules applied for the collection of the county levy in said counties. This legislation was effective from the date of passage.[44] Note: By one act of the General Assembly, many Kentuckians owed five years of back taxes and county levies. It would be understandable if the Homestead Act and relocation were given serious consideration.

It was deemed lawful for any assessors who had been appointed by the county courts since 1 January 1865, or appointed, elected, and qualified hereafter, to make their assessments as required by law, provided the assessors returned their tax books to the county court at any court term held on or before the first Monday in November 1865. The tax books were to be delivered to the collectors of the tax immediately. Revenues were to be paid into the treasury by 1 March 1866. The act was effective on passage.[45]

Sheriffs were given extended time, to 1 June 1866, to submit their listings of delinquent members of the enrolled militia in their respective counties. This included militia members in the military service of the United States or the state of Kentucky, during 1864, and those who had enlisted in the service of the Confederate States. The auditor was directed to give said sheriffs, respectively, credit for the military fines assessed against such persons. The act was effective upon passage.[46]

1865 (3 June)

The act empowering the governor to raise a force of five thousand men for the defense of the state, approved 26 January 1864, was repealed under this legislation, however “nothing in this Act shall be construed as to require the immediate mustering out of any portion of the force raised under said Act and who are presently in service.” Said forces were directed to be mustered-out as soon as the safety of the State could permit. The act was effective upon passage.[47] Note: The Acts of the General Assembly are a principal resource for researching military history in Kentucky. For example, there are several acts approved in 1865 that detail the payment of arrearages owed by the state to the battalion of Harlan County State Guards.

RESEARCH CHALLENGES & SUGGESTIONS

- How much money was borrowed by the government of Kentucky for the war effort and from whom? When was the war debt paid in full?

- What role did the Homestead Act play in restoring the dream of land ownership to Kentucky soldiers (or their families) whose land had been sold for nonpayment of taxes? The Bureau of Land Management has an excellent website for tracking Kentuckians who left the commonwealth and relocated to states in the federal government public domain, such as Missouri and Illinois. Scanned images of the presidential grant conveying title to the landowner are included on the site.

- Research deeds on file with the county clerk’s office or the Kentucky Department for Libraries & Archives (KDLA) to determine when properties were purchased and sold. For properties sold by the master commissioner for delinquent taxes, the grantor may be listed under “C” (for commissioner) rather than the name of the person owning the property or there may be a separate set of volumes for tax sales.

- Were any of your Civil War ancestors listed as absent without leave (AWOL) between 1 June and 15 December? Perhaps they went home to harvest crops or to ensure their taxes were paid. Order, or re-order, pension files from the National Archives in Washington, C. and check dates of service, including any AWOL notations. (By re-ordering pension files you obtained years ago, you may find additional information when you receive the complete file.)

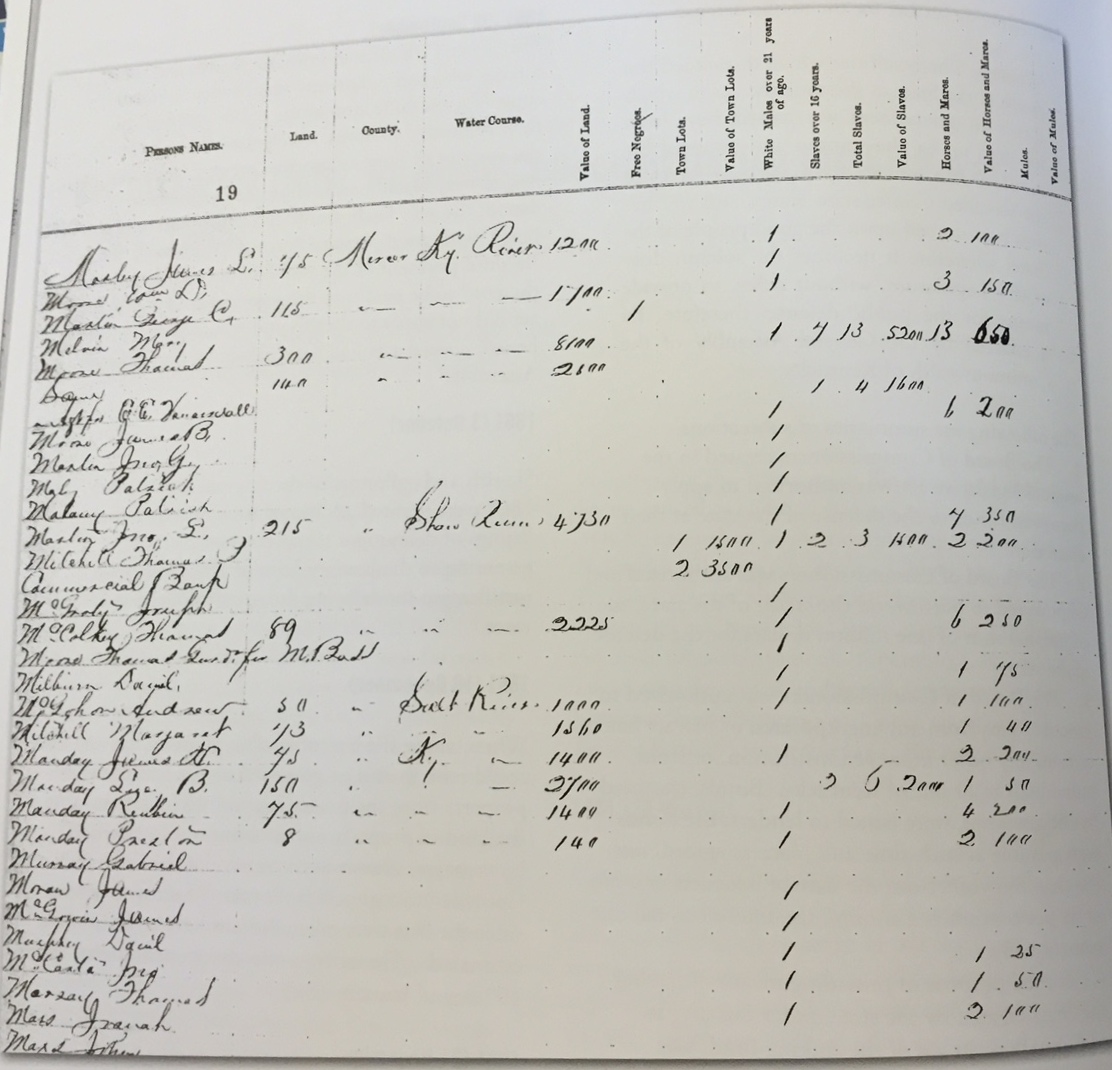

- Legislation affects tax list headers—just as legislation affects today’s tax forms. Tax headers in 1841 differ significantly from tax headers in the 1860s. Tax lists are not a “Once you have seen one, you have seen them all” type of record.

- Research court records on the local level and Franklin Circuit Court for cases involving sheriffs and other persons involved in tax collection.

- Research area newspapers for publication of tax sales or coverage of trials regarding county officials and revenue collection.

- Research the Acts of the General Assembly for legislation regarding state and federal troops, slavery (including runaways), and education during the Civil War.

About the Author: Ms. Adkinson’s 35 years of public service have been dedicated to Kentucky Land Patents. For 6.5 years she worked at the Kentucky Historical Society in the Records Preservation Lab. She has been associated with the Secretary of State’s Land Office since 1984. In 2011 the Kentucky Historical Society presented Kandie the Anne Walker Fitzgerald Award for her articles regarding tax list research published in “Kentucky Ancestors.”

About the Author: Ms. Adkinson’s 35 years of public service have been dedicated to Kentucky Land Patents. For 6.5 years she worked at the Kentucky Historical Society in the Records Preservation Lab. She has been associated with the Secretary of State’s Land Office since 1984. In 2011 the Kentucky Historical Society presented Kandie the Anne Walker Fitzgerald Award for her articles regarding tax list research published in “Kentucky Ancestors.”

[1] Acts of the General Assembly Passed at the Called Session, 1861, 20-21.

[2] Acts of the General Assembly , 1861, 1862, & 1863, 4-5.

[3] Ibid, 8-9.

[4] Ibid, 18.

[5] Ibid, 32-33.

[6] Ibid, 42-43.

[7] Ibid, 43.

[8] Ibid, 57-58.

[9] Ibid, 58-59.

[10] Ibid, 62-64.

[11] Ibid, 68-69.

[12] Ibid, 195-96.

[13] Ibid, 70.

[14] Ibid, 76.

[15] Ibid, 80-82.

[16] Ibid, 90-92.

[17] Ibid, 331.

[18] Ibid, 331.

[19] Ibid, 331.

[20] Ibid, 339.

[21] Ibid, 339-40.

[22] Ibid, 351.

[23] Ibid, 367.

[24] Choses is a legal term. Henry C. Black, Black’s Law Dictionary (St. Paul, Minn., 1933), 323-24.

[25] Ibid, 375.

[26] Acts of the General Assembly, 1864, 4.

[27] Ibid, 19-20.

[29] Ibid, 74-75.

[30] Ibid, 118-19.

[31] Acts of the General Assembly, 1865, 9.

[32] Ibid, 9.

[33] Ibid, 16.

[34] Ibid, 17-18.

[35] Ibid, 26-27.

[36] Ibid, 134.

[37] Ibid, 39.

[38] Ibid, 82-83.

[39] Ibid, 90-91.

[40] Ibid, 368-69.

[41] Ibid, 119.

[42] Chapter 1584, Ibid, 121.

[43] Chapter 1698, Ibid, 129.

[44]Chapter 1735, Ibid, 131.

[45] Chapter 1740, Ibid, 130-31.

[46] Chapter 1788, Ibid, 137.

[47] Chapter 1826, Ibid, 141.

free sample just need to remember that the that nix wish transform.