By: Julie Maio Kemper, Curator, Museum Collections & Exhibitions, Kentucky Historical Society

Around a corner in the Kentucky Historical Society’s permanent exhibit, “A Kentucky Journey,” two portraits sit enclosed in a large glass case.

These are the images of Dennis and Diadamia Doram, dated 1839. Like many prosperous 19th century Kentuckians, the Dorams paid to have their portraits made. The difference is that these two people started life as slaves. Despite cultural and legal obstacles, they became business and land owners in Danville, Ky., well before slavery was abolished. Looking at their faces, it is easy to imagine they are gazing at the American dream in the distance. It is not the same view as the European-Americans in their community, yet the Doram family was able to achieve many of the things that make up the American dream: home ownership, successful businesses, educated and successful children, social standing, and freedom.

Treasure Found

The portraits themselves have an interesting history. Viola Gross of Frankfort, Ky., a great-granddaughter of Dennis and Diadamia Doram, spent years researching the genealogy of her family.[i] She learned that two family portraits had been found in a Boyle County barn that belonged to another descendent of the Dorams. Mrs. Gross contacted the Kentucky Historical Society about acquiring the portraits which led to the Kentucky Historical Society Foundation raising funds to purchase the portraits in July 2000.

The portraits were painted by Patrick Henry Davenport (1803-1890), the son of a Danville, Ky., tavern owner and banker. Davenport was educated at Danville Academy and became an accomplished portrait artist despite little training.[ii] He later moved to Illinois, but during the 1820s and 1830s painted the business elite of Kentucky’s Boyle, Madison, Mercer, Garrard, and Lincoln counties. The portraits of Dennis and Diadamia Doram were painted in 1839 and are believed to be the only paintings of African Americans Davenport created. He also painted portraits of Mrs. Isaac Shelby, the wife of the first Governor of Kentucky, and abolitionist John Brown, both of which are in the Kentucky Historical Society collections.

Today, after extensive conservation, the portraits are in very good condition. It is once again possible to study the faces of these extraordinary people and their story.

Dennis and Diadamia Doram

Dennis and Diadamia Doram are notable for their achievements at a time when social and political forces were aligned to prevent any glimmer of the American dream for people of African descent in this country.

Dennis Doram was born into slavery at Danville, Ky., in 1796. His mother Lydia Doram was owned by General Thomas Barbee, who was also her father. Dennis’s father was also named Dennis Doram. Family stories say he was at least part Native American and was not a slave.[iii] When Thomas Barbee died, the younger Dennis was less than a year old.

![Deed of emancipation between Moses O. Bledsoe and [Taylor] Gibson, 7 March 1836](http://kentuckyancestors.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/slide-21-Diadamia-freedom-doc-191x300.jpg)

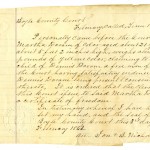

Diadamia Taylor Doram was born in 1810. She, her mother Cloe, and her siblings were the slaves of Moses O. Bledsoe of St. Louis, Mo. Diadamia’s father, Gibson Taylor, was a free man of color. In 1814, Gibson Taylor paid Bledsoe $700 to free his wife and children. The Taylor family moved to Kentucky shortly afterwards. Diadamia was raised in Harrodsburg, Ky., but there is little else known about her youth. The next documented event in Diadamia Taylor’s life is her marriage to Dennis Doram on Feb. 15, 1830 in Mercer County, Ky. Together, these two former slaves embarked on an unlikely journey that other African Americans with less education and fewer opportunities could not take.

History Revealed

One hundred and seventy years after the Doram’s marriage, their great-granddaughter, Viola Gross, brought the Doram paintings and the Kentucky Historical Society together, but Mrs. Gross also had treasures of her own. In 2006, she donated 65 original documents pertaining to the Doram-Rowe family to the Kentucky Historical Society. This collection, supported by other research, pinpoints steps the Doram family took on their path to achieve the American dream.

Freedom:

The Doram-Rowe Family Collection details the family story after the marriage of Dennis and Diadamia. The one exception is the earliest document in the collection. Dated 1829, the document is a certificate of freedom verifying Diadamia Doram’s release from slavery on April 11, 1814. Thirty-four years later, Diadamia’s daughter Martha A. Doram, also secured a certificate of freedom.

It too is part of the collection. According to Mrs. Gross, Martha (who was her grandmother) sought this document because she was about to get married. Perhaps Diadamia used the same reasoning since she married Dennis one year after the date of her freedom documents. Another certificate of freedom in the Doram-Rowe Family Collection from 1839 includes the names of Dennis and Lydia Doram, Dennis’ parents. It was created in Tennessee where the elder Doram couple had moved years before. The document is peculiar because Dennis Sr. is believed to not have been a slave and was deceased by 1839. The 1840 Federal Census indicates that Lydia Doram may have been living with her son Dennis and Diadamia. Perhaps she sought this confirmation of freedom before she left Tennessee.

Home ownership:

Documented in both the Doram-Rowe Family Collection and the Boyle County records is a land deed for the purchase of a lot of land on “the Main” street in Danville, Ky., by Dennis Doram on Feb. 1, 1836. The lot had a brick building on it and some outbuildings. Doram paid 1/3 of the cost up front and paid the rest in installments over two years. If and how long the family lived there is unknown as the Dorams continued to purchase town lots. This includes a house on 3rd Street that still stands today (now 233 Martin Luther King Blvd.) and land with a house on the Danville turnpike in 1854.

Between 1837 and 1860 the Dorams’ purchased over 300 acres of land, most along the Dix River in Boyle County. One of the first of these purchases was made from an heir of General Thomas Barbee, Dennis’s previous owner. General Barbee’s nephew, Thomas Barbee, sold the Dorams a little over six acres of land 10 years after General Barbee’s will freed Dennis. The Dorams also purchased land in Indiana. Although purchased from different owners, the land lots appear to be adjacent to each other. How they used this land is unknown. It is important to note that although the Doram’s were the wealthiest free blacks in Boyle County, Ky., they still owned only about 1/5th of the amount of land compared to the largest white land owner.[vi]

Successful businesses:

The 1860, county tax records reported that the Doram family held property valued at $10,800. This included farm land, four town lots, eight horses, thirty cattle, thirty hogs, one goat, one bull and one slave. The Doram land was most likely used to raise a variety of crops, but there might have been a good amount of hemp too.

Family stories indicate that Dennis Doram also ran a rope factory and a hemp business. Evidence supporting that includes an account receipt for the year 1840 in the Doram-Rowe Family Collection. It lists rope and cord sold to D. Yeiser from 1835-1839. Also, one of Dennis and Diadamia sons and Dennis’ brother are listed in the 1860 Federal Census with an occupation of “rope spinner.” Yet in the same year Dennis is listed as “farmer.”

Educated and successful children:

Dennis and Diadamia Doram had 12 children.[vii] Perhaps two of the 12 did not make it to adulthood. Of the few personal letters in the Doram-Rowe Family Collection most are from their children. Along with other documents, it is possible to gather who the children were and how they were raised.

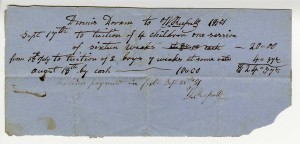

An 1851 paid receipt in the Doram-Rowe Family Collection written by Danville school teacher Willis Russell proves that the Doram children were educated.

The 1850 Federal Census confirms that all of their children from age 7 to 17 were enrolled in school. Dennis and Diadamia’s daughter, Sarah, attended Berea College in the 1870s.[viii] It is unknown if any of their other children continued to a higher education, but it indicates that the family treasured education for daughters as well as sons. A generation later grandson Thomas Madison Doram, earned a doctorate in veterinary medicine. He was the second African-American to do so in the United States.

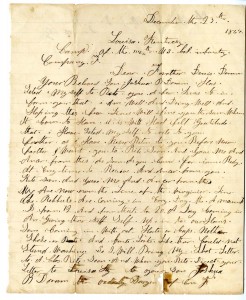

On December 23, 1864, Joshua Doram wrote to his father from Louisa, Ky. (Louisa is located in eastern Kentucky near the Virginia state line). Joshua and his older brother Thomas both joined the 114th United States Colored Troops. His short letter mentions that Confederate troops were surrendering every day and arriving in little more than rags for clothes.[ix] The brothers joined the United States Army together, as was common at the time, mustering at Camp Nelson in Kentucky. The 114th Regiment participated in the Siege of Petersburg and the Appomattox Campaign and was in Appomattox, Va., when the treaty documents were signed.

Both brothers returned home and started businesses. Joshua became a barber and later ran a grocery on Second Street in Danville.[x] He may have had a side business as well. According to the Semi-weekly Interior Journal of Stanford, Ky., Joshua was accused of selling alcohol on several occasions in the dry county of Boyle. Thomas went a different direction. After the war, Dennis Doram loaned him money to buy a farm.[xi] Tax records and newspaper accounts indicate Thomas was raising horses. He was still buying horses in the 1880s and is listed in the 1895 Wallace’s American Trotting Registry. Thomas sold his farm in 1902 at the age of 65.[xii]

Another Doram son served in the United States military. Robert Cassius Clay Doram was a Buffalo soldier. He enlisted in 1868 and left the service in 1879 due to disability. The Doram-Rowe Family Collection includes three letters he wrote home. Military records list Robert’s occupation as a mason, yet he is not listed in business or census records after 1870.

Information on all of the 12 children has not yet been found, but there are pieces of information that help tell the story. For example, the Interior Journal remarks about a dispute regarding Susan Doram’s rock quarry in 1898. This was 10 years after she had her maiden name restored as her legal name by the county court.

Social standing:

Research indicates that Dennis and Diadamia Doram had good standing in the community. Their roles as free blacks who were land owners speak both to their reputation and their ability to build relationships outside the African American community. There is one indication that Dennis Doram was not well regarded by everyone. In 1850, Fred Visschon refused to allow Dennis to purchase his land which was going up for auction. For some reason the family kept this document and it is in the Doram-Rowe Family Collection.

Dennis was a leader in the African American community of Danville. Receipts in the Doram-Rowe Family Collection show that Dennis paid another person’s debt on at least two occasions. During the Civil War, Dennis had served as an intermediary for a least a two soldiers in the United States Colored Troops. Elijah Irvine of the 114th United States Colored Troops sent Dennis $80 to give to his wife, Sophia. He requested that Dennis open a bank account for Sophia and approve how she spent that money.

Family stories indicate that he helped start a school for the higher education of African Americans.[xiii] This is supported by the fact several African Americans, lead in part by Dennis’s son Gibeon Doram, started creating schools for newly freed slaves after the Civil War. Dennis was also a delegate of the First Convention of Colored Men of Kentucky.[xiv] This organization was created in 1866 to advance the rights of African Americans in Kentucky, starting with lobbying the Legislature for voting rights.

Another indicator of social status in pre-Civil War Kentucky was slave ownership, and Dennis Doram did own slaves. There is no documentation in the Doram-Rowe Family Collection that indicates ownership of slaves. Other records provide evidence that Dennis Doram was a slave owner. He freed a woman named Mary who was about 25 years old in 1846. A year later, he freed a woman named Lydia.[xv] The 1860 Slave Schedule lists Dennis as owning one male slave aged 56 and that there was one “slave dwelling” on his property.

Because Dennis was responsible for most legal transactions, there is little evidence about Diadamia’s character. She is listed as Dennis’s wife in only one of the land deeds in the Doram-Rowe Family Collection. A Freedman’s Bank record from 1873 gives some additional information, but nothing of her character. An obituary in 1883 describes Diadamia as “a very worthy woman” and “a devoted member of the Methodist Church for over fifty years.”

Pieces of the American Dream

The portraits of Dennis and Diadamia Doram illustrate one family’s quest for the American Dream. Not all the pieces are there, and what is there prompts questions about African Americans owning slaves, the rights of free blacks in pre-Civil War Kentucky, and 19th century commerce. At the Kentucky Historical Society, the portraits are used to ask these questions. But they also serve as reminders that there are entire generations of African American families that have little or no documentation to reveal their story.

In March of 1866, Dennis Doram served on the finance committee for the First Convention of Colored Men of Kentucky. The committee drafted a statement of intentions. A portion of it seems to embody Dennis’ view of the American Dream.

“We are native and to the manner born; we are part and parcel of the Great American body politic; we love our country and her institutions; we are proud of her greatness and glory in her might; we are intensely American, allied to the free institutions of our country by sacrifices, the deaths and the slumbering ashes of our sons and our fathers, whose patriotism, whose daring and devotion, led them to pledge their lives, their property and their sacred honor, to the maintenance of her freedom, and the majesty of her laws. Here we are intended to remain, and while we seek to cultivate all of those virtues that shall distinguish us as good and useful citizens, our destiny shall be that of earnest and faithful Americans, and we recognize no principle, we allow no doctrine that would make our destiny, other, than the destiny of our native land and fellow countrymen.”

About the Author:

Julie Kemper has a Bachelor of Science in Historic Preservation from Southeast Missouri State University and a Master of Arts in History and Museum Studies from the University of Missouri – St. Louis. She has been working in museums and historic sites for over 20 years. She served as director of the George C. Marshall Museum in Lexington, Va., and Eugene Field House in St. Louis, Mo. She left her position as Curator of Exhibits at the Missouri State Museum in Jefferson City, Mo., to join the KHS staff as a curator in 2011.

Julie Kemper has a Bachelor of Science in Historic Preservation from Southeast Missouri State University and a Master of Arts in History and Museum Studies from the University of Missouri – St. Louis. She has been working in museums and historic sites for over 20 years. She served as director of the George C. Marshall Museum in Lexington, Va., and Eugene Field House in St. Louis, Mo. She left her position as Curator of Exhibits at the Missouri State Museum in Jefferson City, Mo., to join the KHS staff as a curator in 2011.

[i] Gross, Viola. Two Hundred Years of Freedom: A Genealogy and History of the Doram, Rowe, Barbee and Allied Families. (Kinnersley Press, 2003), 2.

[ii] White, Judson. “Patrick Henry Davenport: Pioneer Illinois Portrait Painter” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. Vol. 51, No. 3, (Autumn 1958), p. 250

[iii] Gross, Two Hundred Years of Freedom, 45.

[iv] Thomas Barbee’s Will, Mercer County, Kentucky. Book 2, Box NO. 22 [M310], pp.31-34

[v] Doram, Tai. “Heritage Lost, But Now Found!” (unpublished and undated manuscript), 26.

[vi] Brown, Richard C. “Free Blacks in Boyle County.” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 87 (1989) p..

[vii] The names of the children vary depending on the source, but the number seems consistent.

[viii] Sears, Richard D. Berea Connection. Special Collections & Archives, Hutchins Library, Berea College, 1996, p. 42.

[ix] Letter from Joshua Doram to Dennis Doram 23 Dec. 1864. Doram-Rowe Family Collection, 1829-1975 MSS 21. Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort, Ky.

[x] U.S. City Directories 1821-1989, Danville, Kentucky, 1877-78, p. 132.

; Eighth Census of the United States, 1860.

[xi] Will of Dennis Doram, Oct. 17, 1870. Doram-Rowe Family Collection, 1829-1975 MSS 21.

[xii] Interior Journal. (Stanford, Ky.) 1881-1905, February 3, 1882, and January 10, 1902.

[xiii] Doram, Tai. Heritage Lost, But Now Found! Unpublished and undated manuscript. p.29

[xiv] Astor, Aaron. Rebels on the Border: Civil War, Emancipation and the Reconstruction of Kentucky and Missouri. Louisiana State University Press, 2012. P.146

[xv] Gross, Two Hundred Years of Freedom, 62.

free sample barely need to bear in mind that the that nothing will transform.

I believe this story may be even more intricate. My second great-grandfather is listed on the 1850 census as living with them; he was mulatto and free, aged 13. My family is trying to piece together how he came to live with the Doram’s. Please contact me at your earliest convenience, so that the story of both families can be fully expressed.

WOW just what I was looking for. Came here by searching

for nebraska