By: Linda Colston, KHS Library Technician and Genealogist

Editor’s Note: The following report comes to us through the research that was conducted for the first Kentucky Ancestors Town Hall event in 2017.

The information the family had indicated that General May had been a Deputy Sheriff in Laurel County, Kentucky and had also been executed at Eddyville Prison on 27 Jun 1913. The family was interested in knowing how this came about.

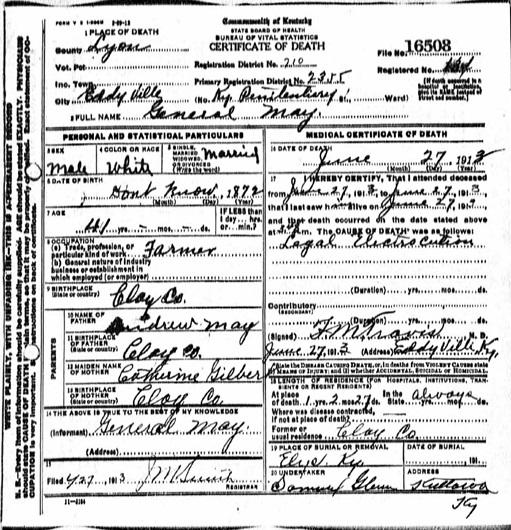

The search began with a look at his death certificate. Kentucky started keeping death certificates at the state level in 1911[1]. Since he died in 1913, a death certificate should have been created. It was found in Lyon County, which is where Eddyville Penitentiary is located.[2] According to the death certificate, General May died on the 27 Jun 1913 due to a legal electrocution. He had been in the prison one year, two months and 27 days and he formerly lived in Clay County, Kentucky. He was buried in Elye, Kentucky which is the cemetery used by Eddyville. The informant for the ‘Personals and Statistical Particulars’ section was General May. It is a little unusual for the informant to also be the deceased, but it does make sense under the circumstances as he was awaiting his own execution. General May indicated that he was 41 years old, married and born in 1872 in Clay County, Kentucky. He did not know the month or day that he was born. His occupation was as a farmer and his parents were Andrew May and Catherine Gilbert, both born in Clay County, Kentucky.

To determine why General May was sentenced to death, a search for the case file was necessary. Per Kentucky Ancestry, the records were housed at the Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives (KDLA)[3] In the Kentucky Records section, Drawer 1 the microfilm for the Court of Appeals Index was found on roll J000271. The roll identified the case of the Commonwealth of Kentucky vs General May in Laurel county as Case #41612. The actual file was brought down from archival storage and as seen below, it is a rather large file:

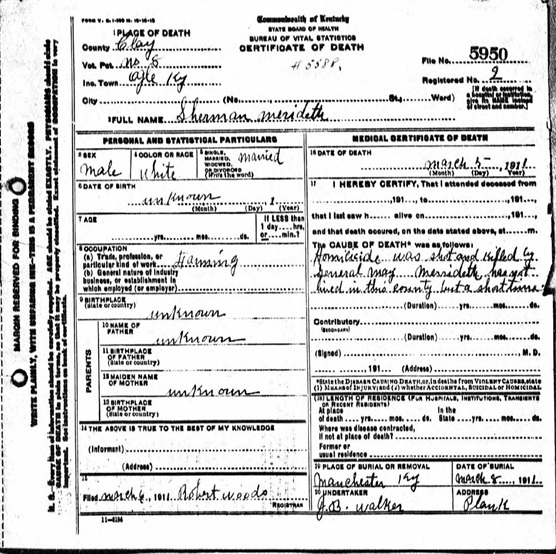

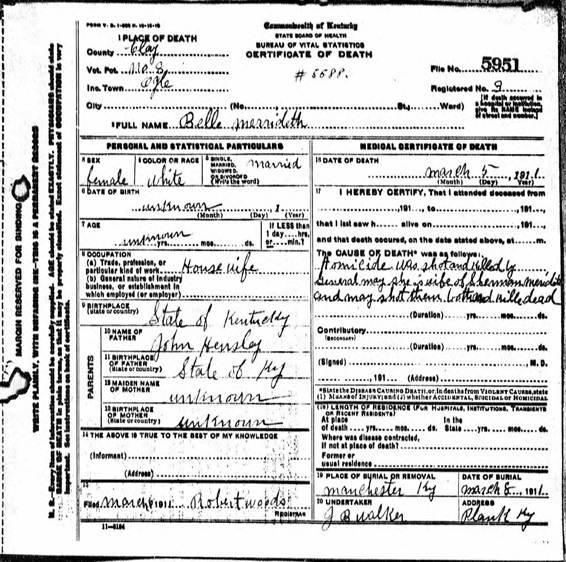

The trial transcripts indicated that General May underwent two separate trials. First for the willful murder of Sherman Meredith and then for the willful murder of Belle Meredith, Sherman’s wife. Both were murdered on the 5th of March 1911. At the first trial, General May admitted killing Sherman but claimed it was self-defense stating that Sherman had drawn his gun first. He was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. He was subsequently sent to the Penitentiary in Frankfort to serve out this sentence. Following that trial, he was then tried for the murder of Belle Meredith which also resulted in a guilty verdict and this time he received a death sentence.

The question then becomes, ‘how did this come about?’ In looking at the various records, including transcripts, prison records, articles and other documents, a picture of General’s life emerges. He was the son of Andrew and Catherine (Gilbert) May and one of many children. He was born ca 1875 on Otter Creek in Clay County.4,[5],[6],[7] As seen on his death certificate, General was not really sure of his date of birth and when asked how old he was, in his testimony, he stated, “Well, I don’t exactly know. I am some over thirty five years old.[8] Based on the census records, he was closer to being born in 1875 than 1872. He also testified that he had no education.

At the age of 14, May was involved in an incident which resulted in the charge of horse stealing. The records show that he served time in the Kentucky State Penitentiary in Frankfort from the 17th of November 1893, at the age of 16, until he was released on 17 Mar 1896.[9] During his trial he stated that he was trying to help a woman, by the name of Julia Jackson, who he alleged was the one who actually stole the horse. He testified that he took the blame to “save a woman out of the penitentiary,–to keep her from going…” He went on to state that “If I stood trial I wouldn’t have been proved guilty.”[10] This incident appears to be the beginning of his involvement with the law.

On the 21st of March 1896, just days after getting out of prison, he married Louisa Hubbard.[11] In the 1900 census records, General and Louisa were living with his parents. Per the information provided, General was unable to read or write and was working as a farm laborer. [12] It is not clear if they had any children. There were two grandsons listed, Blaine age 7 and Charles age 3. General’s 30 year old sister, Louisa, was also in the household. One or both of these children may have been hers, or Blaine may have been hers and Charles may have been General and Louisa’s child. Further research may clarify this.

This may also have been the period that he was a Deputy Sheriff. Per several newspaper reports, General May worked a couple of years as a Deputy Sheriff.[13], [14] A search in Bell, Knox, and Clay Counties did not produce any results to establish if or when this occurred, however, not all of the records for this time period either exist or are available.

At some point, he and Louisa must have divorced because on the 7th of October 1905, General May married Vina Mills in Bell County.[15] Per the 1910 Census, this was the second marriage for both General and Vina.[16] This census also shows two children, a 3-year-old daughter, Cecil and a 2-year-old son, Basil. General’s younger brother, Dill, was also living with them in Knox County and both worked in the Coal Mines. Sometime between the 1910 census and the 1911 murders, Vina disappeared. At the trial, Mr. Gaddie and Mr. Renfro testified that they had heard that General had killed his wife. General stated that his first hearing of that was during the trial and their testimony. He went on to say that she was living.[17] On cross examination, General stated that his wife was in Lockland Ohio and had been there nearly a year and a half. He stated that he heard from her about every two weeks and he denied the claim that he had killed her at one of the mining camps on the L.&N. Railroad just south of Jellico. He went on to state that he was not familiar with that road and had never been there. He testified that she lived at the depot in the Ely Hollow and her sister had come down from Ohio to get her and she went with her. They had gotten into a disagreement over something he read in one of the letters she had received from her sister. As a result, he gave her money and she got on the train. He was asked “Didn’t you and her leave here at a time when old man Renfro knew it and move to Tennessee? Isn’t that the last time she was ever seen in that mining camp?” May responded, “No sir, she left along the 1st of June, and I left there in September that fall until my garden come off. We had about an acre and a half of garden there and when it come off I left. Then I went to Four Mile just across the line.”[18]

It was reported that no one had seen her since. Her children ended up in two different homes. In the 1920 census records, Cecie is found living with Major May[19]. The only Basil, of the right age, was found in Magoffin County living with a Sarah May who identified him as her grandson.[20] This may or may not be General’s son. It is possible that if Vina left and went to her sister’s, as General claimed, she might have taken Blaine with her. Although, one might think that she would have taken the youngest.

Based on the records searched, including newspaper accounts, General May had a history of incidents where guns and disagreements abounded. He carried a 38 caliber pistol which he fondly called “Old Huldy”. Old Huldy was reported to have eight notches carved into the handle and this was believed to be the results of a notch carved for each person General had killed over the years.[21], [22], [23], [24] During his testimony, General denied killing 7-9 other people. He stated that the only trouble he ever had was on Otter Creek in Clay County and Ely Hollow in Knox County.[25]

Per an article written in the Louisville Courier Journal on the 8th of January, 1900, during a trial before a Magistrate at a schoolhouse on Otter Creek, Clay County, Kentucky, a fight broke out. Lige Lewis, a brother of the ex Sheriff, Joe Lewis and General May were both reported to be dead.[26] However, this does not appear to be the case. Per a later article, General had received 12 bullet wounds and survived.[27] General was also credited with shooting Lige Lewis’s arm off.[28] Whether this occurred at the time of the incident in 1900, or later is unclear.

In other articles, it was reported that he admitted to killing John Lawson in Knox County around December of 1910, killing Mart Smith, in Knox County in 1909 and shooting the arm and leg off Jim Stubblefield, who had been a witness in the Goebel murder trials.[29] By the time of the incident with the Meredith’s, General May already had a reputation, along with his buddy, Old Huldy, of being an ornery individual.

Prior to the fatal incident in March of 1911, General testified that he had been living at Four Mile in Bell County.[30] His mother lived at the old home place on Otter Creek in Clay County. The home place was about three quarters of a mile from the Meredith’s property and the John Duff’s house was below that and right off the road referred to as Knob Lick Branch.[31], [32] General testified that he was going to move back to the home place to help them with the work as he was tired of working the coal mines. He stated that he spent the night at John Duff’s home the Saturday before the murders.[33]

On that Sunday, the 5th day of March 1911, Sherman Meredith, Belle Meredith, his pregnant wife, John Henry Meredith, their 4-year-old son and Farmer Freeman were headed down the road to visit with Gabe Smith, who was selling out and leaving the area. The Meredith’s were going to see what was available and Sherman was particularly interested in a mattock[34], and Freeman went with them to continue to discuss a trade and to purchase some potatoes from Mr. Smith.[35]

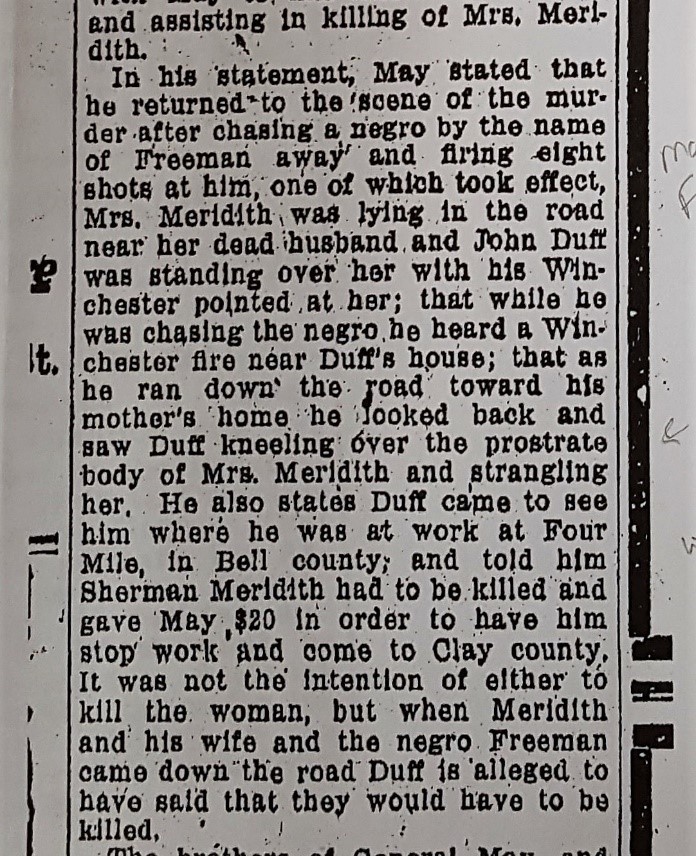

Per General Mays testimony, as the Meredith’s were walking by, Sherman called out to General to talk at the paling (fence). They chatted for a few minutes about the coal mines and Generals brother renting a home from John Duff. The conversation took a turn to an issue that had arisen between Sherman Meredith and Generals mother, Catherine. The Mays had been cutting some trees for lumber and per Sherman, some of those trees were on the Meredith property and as such, Catherine owed him $5. The Mays denied this and stated they would not pay. The disagreement heated up and General said that Meredith was the first to pull a gun. There was a bit of a struggle and General testified that Meredith started to pull his gun when General swiped at his arm, pulled his gun out and shot him in the face. Meredith fell and General jumped over the fence when he stated that Farmer Freeman pulled a gun and fired a shot. So, General started returning fire and chasing Farmer Freeman down the road. A bullet hit Farmer Freeman in the heel but he kept running. When asked about Mrs. Meredith, he stated that she was down below Sherman and couldn’t have been hit by his shots. General admitted to firing two more shots at Meredith but stated that Mrs. Meredith was too far away to have been hit by them. After hitting Freeman, May kept running until he reached his mother’s home, saddled a mule and then took off to Knox County.[36] General May claimed that he did not know Mrs. Meredith had been killed until the next day and he thought that he had killed Farmer Freeman as well. Several witnesses testified to his bragging about the murders and getting away with them.

However, he did leave a witness, Farmer Freeman survived the bullet wound and his testimony is significantly different than General Mays. Farmer Freeman was a man of color and identified his father as being Can Freeman. He too lived on Otter Creek in Clay County about a half mile from John Duff’s place. On that fateful day, Freeman testified that he was with Sherman Meredith, starting out at the Meredith home along with Belle Meredith and their child, Johnnie Meredith. Freeman had gone to visit the Merediths as they had been working out a trade for lumber. He went there in the morning and had a meal with them. After the meal, Sherman and Freeman started down to Gabe Smith’s home which was past the Duff home. Mrs. Meredith and Johnny came along and caught up with them after they passed Duff’s home. Freeman wanted to buy some potatoes and Sherman wanted to buy a mattock. They remained there a couple of hours. As they were returning home and passing the Duff’s, General called for Sherman to come back and talk. Farmer remained where he was, a little past the house and closer to the barn. Belle walked back up with Sherman. They stood and talked for a little bit and it appeared friendly as they were “kindly laughing a bit” General was moving around a bit which caught Farmers attention. He was waiting for Sherman as they were still discussing the potential trade. General started looking off in the distance and said something about looking off. When Sherman turned his head to look in that direction, General shot him in the back of the head. Freeman “…saw a lock of hair fly.” Freeman was asked what happened next, Freeman responded “Well, Sherman, when he shot him he pitched over onto his left side like he was trying to look right up in General’s face and his wife grabbed him right here by the coat and went right on down kindly after him, and then General he throwed his pistol right over the fence, I mean the gate or yard fence, and fired it two more times, two more shots right quick, quick as a man could fire.” The shots were fired “Right in the direction of them, right near him and right in the direction of them is where they was fired.” Freeman did not wait to hear if anything was said and just “wheeled around and run”. General chased him firing along the way. When asked if he (Freeman) shot back, Freeman stated that he did not as he did not have anything to shoot with. The last he saw of Belle was her being ‘down over her husband.”[37] One of the bullets did hit Freeman in his foot and per Freeman, the bullet traveled up to the ball of his foot where it remained and was still there the day he testified.

After General May hit Freeman, thinking he had killed him or that he would die from the bullet wound, he ran. He ran over fences, yards, passed people and headed up to his mother’s home. Once there he grabbed a mule and set off for Knox County. As the General ran, he thought that he had killed all the witnesses that could harm him and that he would be ok as the only witnesses left, were all his friends. He knew that he had wounded Freeman, but thought that the type of bullet used would still kill him.[38] Based on statements made, General May, believed that he could and would get away what he had done.

Following the incident, a search ensued for General May and a $500 reward was offered for the apprehension of May who admitted the killing of Sherman but claimed self-defense.[39] On the Thursday following the shooting, Deputy Sheriff J. W. Wilson and his brother Charles Wilson were on their way back from Frankfort, where they had taken some prisoners. They had taken the afternoon train from Lexington to Winchester. While at the station, they recognized May, who was standing in front of Jett’s Saloon, and they promptly arrested him.[40] He was taken to the Pineville Kentucky jail. During the trip to the jail, May boasted about the incident and also told the officers that ‘If they had not taken him unawares, he would have got one of them.’[41] He was taken to the Richmond Jail for safekeeping until he was ready for the Grand Jury.[42] When that time arrived, an order was made by the Clay county Judge to have him brought to Clay County by a Sheriff/Deputy and two guards to avoid any escape attempts.[43]

On April 25, 1911, during the April Term of the Clay County Circuit Court, the Grand Jury indicted General May of the crime of the willful murder. As of the April 26, 1911, General was confined to jail in Clay County without bail. The Clay County Jailor’s half brother was Sherman Meredith and this raised a question in regard to General May’s safety in jail. Due to the question of his safety, while awaiting trial, the judge ordered a special guard be set over him due to being accused of killing the jailors half-brother and his half-brother’s wife. The request was made for someone other than the jailor to guard May and four men were appointed to guard him day and night during his confinement there.[44]

General May was tried first for the murder of Sherman Meredith and following that trial, he was tried for the willful murder of Belle Meredith. General May was represented by Capt. Ben B. Gold, of Barbourville; H. F. Farmer of Manchester and Hazelwood & Johnson of London. The prosecution team was made up of H. J. Johnson, County Attorney; Commonwealth Attorney J. C. Cloyd and Judge H.C. Faulkner of Barbourville.[45], [46] After numerous continuations relating to, among other things, trying to get the witnesses lined up to appear and testify, witnesses were called from Bell, Knox and Clay County to provide testimony.

General had admitted to killing Sherman Meredith and tried to claim it was self-defense. The problem was that no one was able to corroborate Sherman firing a gun or even pointing a gun. Sherman did have a gun, which was later returned to his daughter, but there was no evidence it was fired. In addition, Sherman was shot in the back of the head and this was verified when his body was exhumed to determine the entry and exit wounds of the bullet.[47] Once the trial started, it lasted about a week with the jury sent to deliberations on Saturday, February 25, 1912 and a guilty verdict was returned on Sunday, February 26, 1912.

He was convicted and sentenced to life for the willful murder of Sherman Meredith and subsequently sent to the Penitentiary in Frankfort.[49] He remained in the prison in Frankfort until the court date was set for the trial for Belle Meredith. Although there were newspaper reports of him getting paroled, and then tried for the murder of Belle Meredith, court documents do not indicate that this was the case.[50], [51] The prison records indicated that he arrived at the prison in Frankfort on July 1, 1911 and remained there until he was transferred to Laurel County to stand trial for Belle Meredith’s murder on May 14, 1912.[52]

That trial was scheduled to begin on February 26, 1912 in Laurel County, however it was pushed back to March 14, 1912. During this period, May was taken to London to await the trial.[53]

In the April Session of court in 1912, the Grand Jury indicted General May for the willful murder of Belle Meredith.[54] The facts of the case as identified by the prosecution indicated that:

- General May and Sherman Meredith had a history of problems ranging from killing a dog to the cause of this dispute which was allegedly due to trees and boundary lines. (No information was found regarding the dog incident.) Per testimony throughout the trial, including General Mays own account, there was a long history of problems between the Meredith’s and the Mays.

- General May was at the home of John Duff when Sherman and Belle Meredith, their little boy, John Henry and Farmer Freeman, a neighboring farmer, were passing by on their way to the home of Gabe Smith. May invited them in but they declined the invitation and continued on their way.

- May remained at Duffs, over two hours, even after other visitors had left, until the Meredith’s and Freeman returned. May again invited them in and even offered them whiskey. Again, they refused and continued on their way.

- As they continued toward their home, upon reaching Duff’s barn, May called Meredith to come back to talk with him. Meredith, along with his wife and little boy returned to the fence where May was. Freeman remained on the road by the barn about fifteen or so feet away.

- May met them on one side of the fence and they were on the other side. May engaged him in conversation. During the course of the conversation, May turned slightly and attempted to direct Sherman’s attention to something off in the distance which would require Meredith to look away. Once Meredith looked away, May shot him in the back of the head. As he was falling, his wife was bending over him, at which point, May fired two more shots at them. Then he turned the gun on Freeman and chased him down the road. Freeman escaped with only a wound to his heel.

- He took off to escape but was captured. At that point, he believed that all of the witnesses were dead and that his friends, including Duff, would stand by him.[55]

During the course of the trial, there were multiple witnesses, including Farmer Freeman, the farmer that May thought he had killed. May testified and in his testimony, he denied shooting Mrs. Meredith. He did concede that if he did, it was an accident. Initially he tried to lay the blame on Freeman returning fire and he was only defending himself by shooting at Freeman. But, as it was learned in the trial, Freeman did not have a gun. As in many trials, the accused own words often come back and ‘bite em in the backside’. This happened with General May. Witnesses testified that General May boasted about what he had done. Some of the more damaging statements he made include the following:

“I am alright now…I have got them…I know my fences… I have been in trouble… I know my fences… I have been in trouble… I have got them on this proposition. That no one saw me except (Freeman).[56] I ran him across a ten-acre field and tried to kill him…I shot the S. of B in the heel…I know he will die, because I shot him with a copper-jacket…if he don’t die the jury won’t believe him because they know he has prejudice against me.”[57]

“Yes, sir: what it takes is proof – I have got the proof…Nobody saw it but (Freeman) and Duff-Duff is with me and they won’t believe what (Freeman) swears to….”

“I killed the woman….”[58]

“There is nothing to killing a man…the main thing as to work on your proof…”

“…a dead person couldn’t talk…there were no witness against (me)…. (I) tried to kill them all….(I) didn’t want no witnesses.”[59]

Unfortunately, General May was aware of Mrs. Meredith’s condition and per his own statements, he knew what he was doing when he shot her.

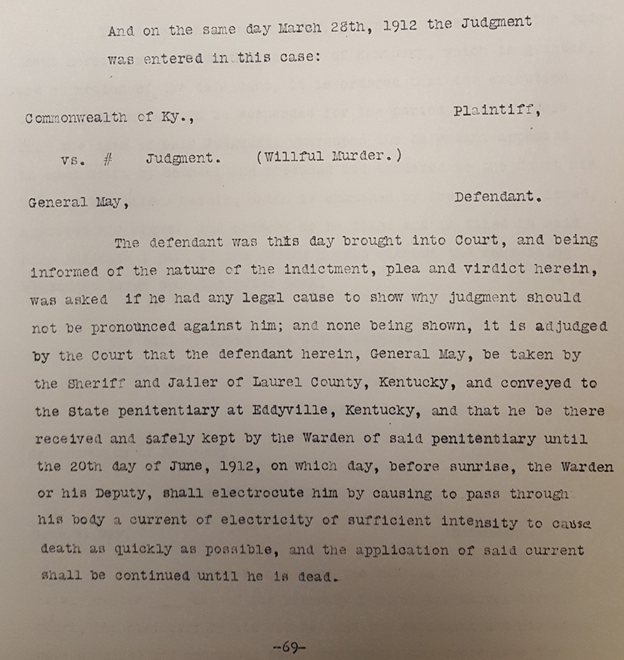

Based on all the evidence and testimony, the jury was not convinced and returned a verdict:

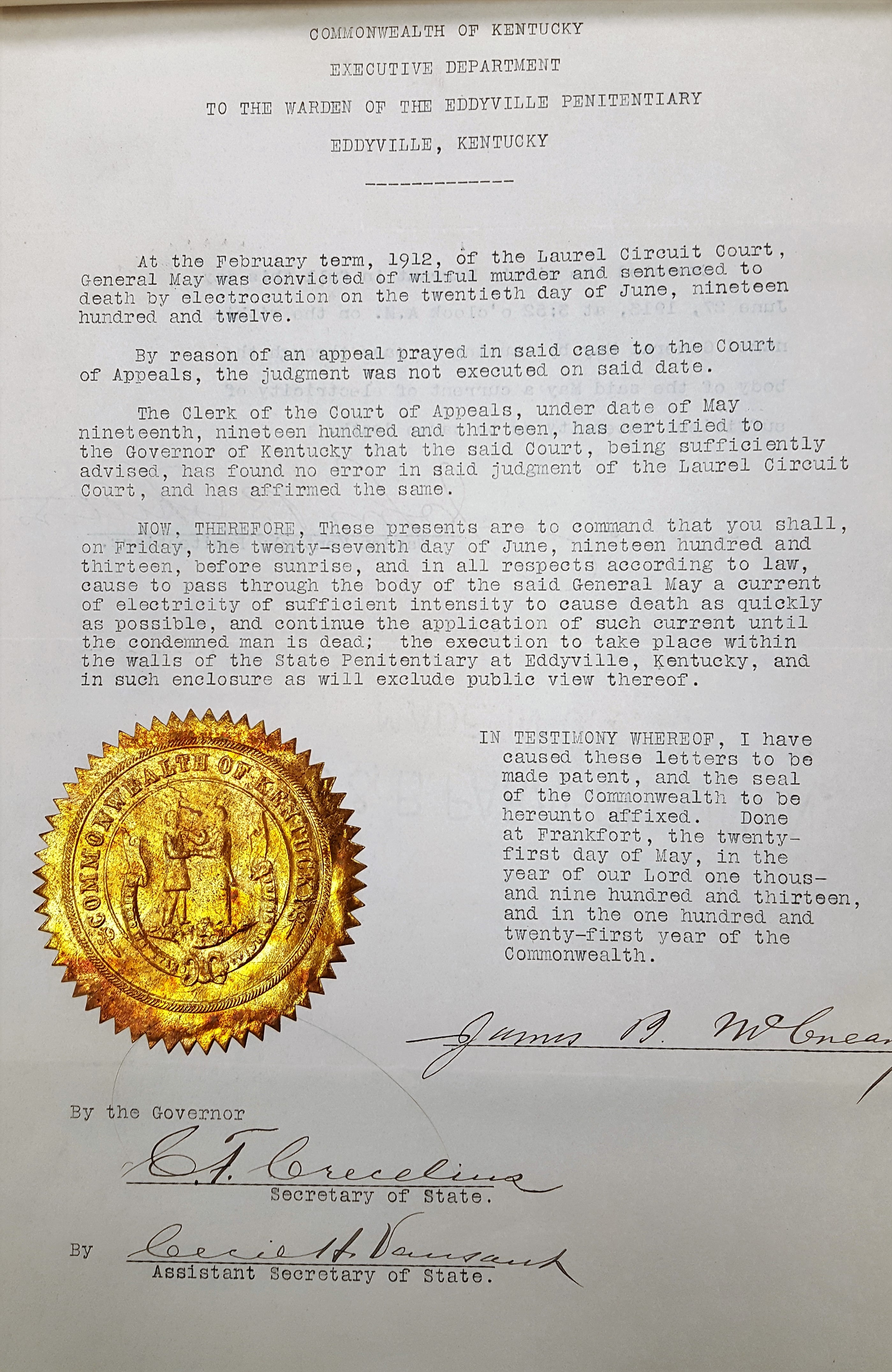

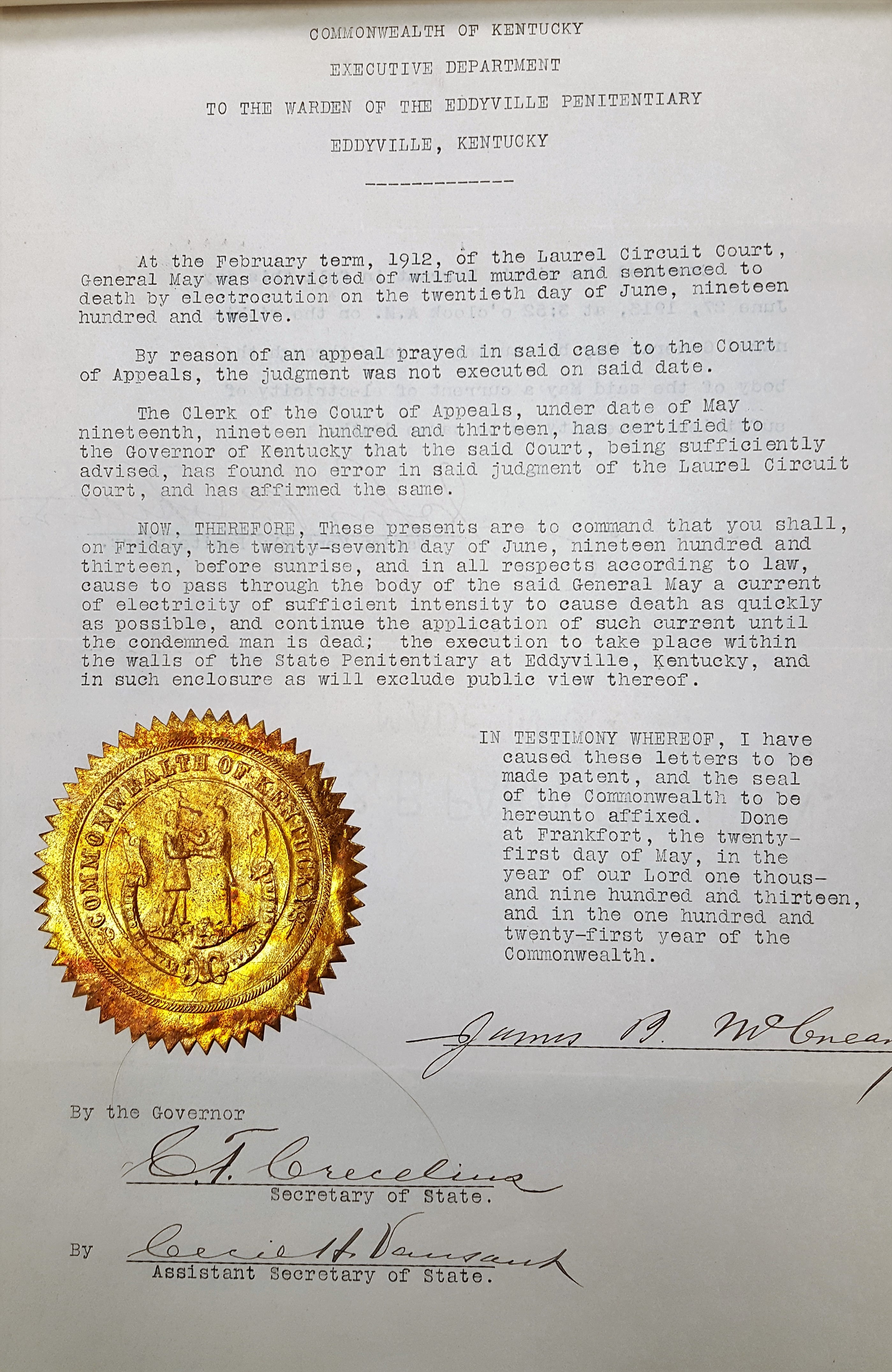

On the same date of the verdict, General May, and his attorney’s, filed an appeal to the Court of Appeals. Because of the appeal, the verdict and sentencing judgement were suspended for 60 days to allow the Court of Appeals time to review the case.[61] The Court of Appeals found no error in the judgement of the decision of the Laurel County Court and General May was then sentenced to die by electrocution before sunrise on Friday, 27 Jun 1913.[62]

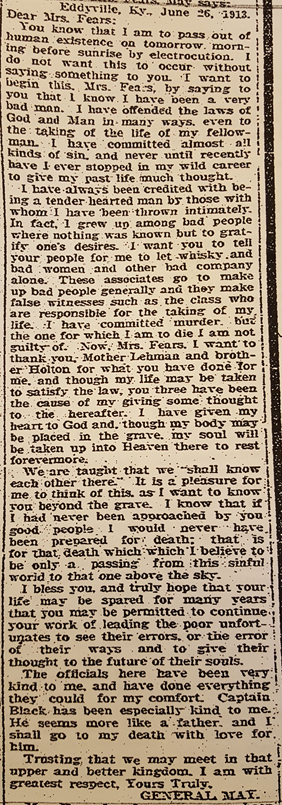

While waiting for the appeal process to wrap up, General spent his last days and weeks at the Eddyville Penitentiary. Approximately three weeks before his execution, he confessed his faith and J.A. Holton, the Prison Chaplin gave him a Christian Baptism.[63] During this time he was visited by prison workers. One of the workers was a woman, Mrs. Fears who General felt comfortable with. This was evidenced by him writing her a letter the day before his death. The guards were kind enough to type the letter for him and the words of the letter are as follows:

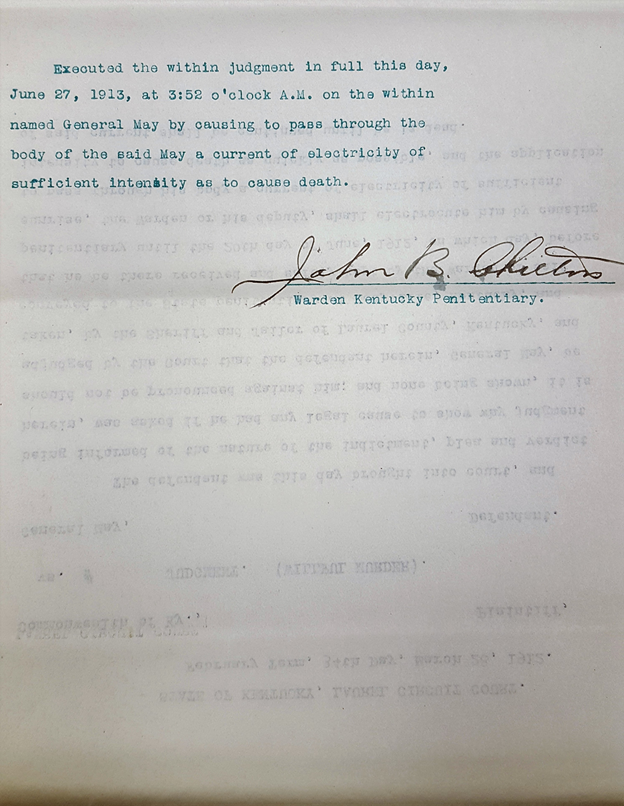

The Governor did not stay the execution and in the wee hours of the morning of June 27, 1913, after eating a hearty breakfast, General left his cell at 3:46 o’clock in the morning. He was accompanied by his death watch, “Lim” Black and the Rev. J. A. Holton, the prison Chaplin. He sat in The Chair and at 3:51 o’clock, 2,200 volts of electricity shot through his body and he was pronounced dead 30 seconds later.[65] It was reported by officials that his execution was the most successful of any of the 18 that had been held previously at Eddyville.[66]

Although General’s story may end here, he did not go without leaving his mark. During his final days, he accepted the Lord and confessed his sins. However, he never admitted to killing Belle Meredith and during his last days he gave a signed confession naming John Duff as the one who killed her. Here is an excerpt from that confession:

[68] While General was no longer around to cause trouble, life went on. Two of his known children were raised by family members, John Duff was indicted and sent to trial for his involvement. John Henry Meredith, who had to witness the murders of his parents, was taken in by his half sister. She took care of him until he reached the age of 16 at which point he left Kentucky and joined the U.S. Navy. In addition, he changed his name from Meredith to Meardy. He married and settled in Connecticut. It is not clear what he may have remembered, but what is clear is that it was tragic enough for him to leave the state and change his name.[69]

While General was no longer around to cause trouble, life went on. Two of his known children were raised by family members, John Duff was indicted and sent to trial for his involvement. John Henry Meredith, who had to witness the murders of his parents, was taken in by his half sister. She took care of him until he reached the age of 16 at which point he left Kentucky and joined the U.S. Navy. In addition, he changed his name from Meredith to Meardy. He married and settled in Connecticut. It is not clear what he may have remembered, but what is clear is that it was tragic enough for him to leave the state and change his name.[69]

This was a turbulent period not only in American History but especially so in Kentucky history. Feuds were going strong in the rural areas of Kentucky and it was nothing for a dispute to be settled with bullets. Politics was a strong catalyst in and at the heart of many of the issues. Around the nation, woman were beginning to fight for their rights and a war with alcohol was intertwined with the Suffrage movement. Old ways of doing things were changing and the world was progressing and changing at a fast pace. It is sad to say, but General May was not the only individual to have lived his life with guns and place the blame on wild women and whiskey.

Kentucky, “Kentucky, Death Records, 1852-1964,” online database, Kentucky Statistics Original Death Certificates – Microfilm (1911-1964), Microfilm rolls #7016130-704803, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com : accessed 4/12/2017), entry for General May, 27 Jun 1913, Certificate #16508.

Kentucky, “Kentucky, Death Records, 1852-1964,” online database, Kentucky Statistics Original Death Certificates – Microfilm (1911-1964), Microfilm rolls #7016130-704803, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com : accessed 4/12/2017), entry for Sherman Merideth, 5 May 1911, Certificate #5950.

Kentucky, “Kentucky, Death Records, 1852-1964,” online database, Kentucky Statistics Original Death Certificates – Microfilm (1911-1964), Microfilm rolls #7016130-704803, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com : accessed 4/12/2017), entry for Belle Merrideth, 5 Mar 1913, Certificate #5951.

Linda Colston is a Library Technician and Genealogist at the Kentucky Historical Society’s Martin F. Schmidt Research Library. She holds a B.S. in Psychology and a M.A. in Educational Psychology and Counseling. She is a member of the Association of Professional Genealogists and has been researching for over 25 years. Continuing Education courses at IGHR; DAR courses GREI, GRE II & DRE III, NGS courses, and attendance at various conferences, seminars, and workshops focused on genealogy. Currently serving as Immediate Past President of the Kentucky Genealogical Society, Past Treasurer of Frankfort DAR Chapter, and owner of Twin Oaks Genealogy.

Sources

Bell County, Kentucky, Circuit Court, Criminal Order Books 9-11 with Index. 1909-1914, General May, microfilm roll 990100, Jun. 1983, Kentucky Department For Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.

Bell County, Kentucky, Circuit Court, Criminal Order Books, 1911-1912, General May, microfilm roll 381625, Jun 1983, Kentucky Department For Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.

Bell County, Kentucky, Marriage Certificate, p 604-605, General May-Vina Mills, 7 Oct 1905; digital image, Kentucky, County Marriages, 1783-1965, Ancestry, (www.ancestry.com, accessed: 7 Apr 2017).

Betty Eddy. “General May Killings Were A Sensation In The Press”. Clay County Ancestral News Magazine, Fall & Winter 2008, Vol. 24, No. 2, p 39-40.

“Bloody Career of Kentucky Character Ends in the Eddyville Electric Chair“, Montgomery Advertiser (Montgomery Alabama), 28 Jun 1913, vol. LXXXIV, issue 179, p. 5, digital image, Genealogy Bank.com (http://genealogybank.com : accessed 19 Jan 2017.

1880 U.S. census, Big Creek, Clay County, Kentucky, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 026, p. 568C, entry for General May, FHL microfilm 1254410, digital image, Ancestry (http: www.ancestry.com), accessed: 7 Apr. 2017.

1900 U.S. census, Otter Creek, Clay County, Kentucky, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 0032, p. 103, sheet 7A,General May, FHL microfilm 12405516, digital image, Ancestry (http: www.ancestry.com), accessed: 7 Apr. 2017.

1910 U.S. census, East Flat Lick, Knox County, Kentucky, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 0105, p. 1A, entry for General May, FHL microfilm 1374502, digital image, Ancestry (http: www.ancestry.com), accessed: 7 Apr. 2017.

1920 U.S. census, Salyersville, Magoffin County, Kentucky, population schedule, enumeration district (ED)68, p. 8B, entry for Basil May, FHL microfilm T625_589, digital image, Ancestry (http: www.ancestry.com), accessed: 7 Apr 2017.

1920 U.S. census, Goose Rock, Clay County, Kentucky, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 54, p. 7B, entry for Cecie May, FHL microfilm T625_566, digital image, Ancestry (http: www.ancestry.com), accessed: 7 Apr. 2017.

Clay County, Kentucky, Circuit Court Records, Index to Criminal & Civil Suites Criminal – Boxes 1-162, Commonwealth of Kentucky v General May, microfilm roll C986869, Feb. 1980, Kentucky Department For Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.

Clay County, Kentucky, Circuit Court Order Book 64. 1911, General May, Kentucky Department For Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.

Clay County, Kentucky, Marriage Certificate, p 604-605, General May-Louisa Hubbard, 29 Mar 1896; digital image, Kentucky, County Marriages, 1783-1965, Ancestry, (www.ancestry.com) accessed: 7 Apr 2017.

“Confession of Man Now Dead”, Lexington Herald (Lexington, Kentucky), 12 Jul 1913, p. 8, digital image, Genealogy Bank.com (http://genealogybank.com : accessed 9 Jan 2017.)

“General May is Caught,”, Lexington Herald (Lexington, Kentucky), 11 Mar 1911, issue 70, p. 4, digital image, Genealogy Bank.com (http://genealogybank.com : accessed 23 Feb 2017.

“‘General’ Is Executed; Had Eight Significant Notches in Pistol,” Muskegon Chronicle (Michigan), 28 Jun 1913, p. 9, digital image, Genealogy Bank.com (http://genealogybank.com : accessed 19 Jan 2017.

“General May Taken to Richmond for Safekeeping,” Courier-Journal (Kentucky), 21 May 1911, p. 7, column 6; digital image, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Louisville Courier Journal (1830-1992), ProQuest, (http://proquest.com: accessed 11 Apr 2017).

“General May Must Die,” Courier-Journal (Kentucky), 25 Mar 1912, p. 3, column 4; digital image, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Louisville Courier Journal (1830-1992), ProQuest, (http://proquest.com: accessed 11 Apr 2017.)

“General May Will Be Tried For Murder,” Courier-Journal (Kentucky), 17 May 1912, p. 2, column 6; digital image, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Louisville Courier Journal (1830-1992), ProQuest, (http://proquest.com: accessed 11 Apr 2017.)

“Governor Gets May Case,” Courier-Journal (Kentucky), 20 May 1913, p. 4, column 5; digital image, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Louisville Courier Journal (1830-1992), ProQuest, (http://proquest.com: accessed 11 Apr 2017.)

Hogan, Roseann Reinemuth, “Kentucky Ancestry A Guide to Genealogical and Historical Research” (Salt Lake City: Ancestry), 1992, pages 78-79

Joyce Taylor Collins. “Meredith vs May”. Clay County Ancestral News Magazine, Fall & Winter 2008, Vol. 24, No. 2, p 36-38.

Kentucky, Corrections Cabinet, Offenses & Punishment, 1891-19120, entry for General May, unpaginated, Kentucky State Penitentiary, Eddyville, microfilm rolls 7011064, 7011099 and 7009894, Kentucky Department For Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.

Kentucky, Corrections Cabinet, Register of Prisoners, 1812-1920, entry for General May, unpaginated, Kentucky State Penitentiary, Eddyville, microfilm 7008244, Kentucky Department For Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.

Kentucky, Corrections Cabinet, Register of Prisoners, 1848-1899, entry for General May, unpaginated, Kentucky State Penitentiary, Frankfort, microfilm 7009891, Kentucky Department For Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.

Kentucky, Corrections Cabinet, Register of Prisoners, 1891-1895, entry for General May, unpaginated, Kentucky State Penitentiary, Frankfort, microfilm 7009898, Kentucky Department For Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.

Kentucky, Corrections Cabinet, Register of Prisoners, 1890-1917, entry for General May, unpaginated, Kentucky State Penitentiary, Frankfort, microfilm 7008244, Kentucky Department For Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.

Kentucky, Corrections Cabinet, Register of Prisoners, 1911-1922, entry for General May, unpaginated, Kentucky State Penitentiary, Frankfort, microfilm 7040453, Kentucky Department For Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.

Kentucky, Court of Appeals, January Term 1913, Commonwealth of Kentucky vs General May, Case File #41612. Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort.

Kentucky, Court of Appeals Index, Commonwealth of Kentucky v General May, drawer 1, microfilm roll J000271, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.

Kentucky, Frankfort Penitentiary, Register of Prisoners, 1911-1936, entry for General May, 11 Jul 1911, unpaginated, microfilm 7009892, Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.

Kentucky, “Kentucky, Death Records, 1852-1964,” online database, Kentucky Statistics Original Death Certificates – Microfilm (1911-1964), Microfilm rolls #7016130-704803, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com : accessed 4/12/2017), entry for General May, 27 Jun 1913, Certificate #16508.

Kentucky, “Kentucky, Death Records, 1852-1964,” online database, Kentucky Statistics Original Death Certificates – Microfilm (1911-1964), Microfilm rolls #7016130-704803, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com : accessed 4/12/2017), entry for Sherman Merideth, 5 May 1911, Certificate #5950.

Kentucky, Department of Corrections, Execution Records, file for General May, Eddyville State Penitentiary, Lyon County, Kentucky Department For Libraries and Archives.

Knox County, Kentucky “Kentucky Birth Records, 1847-1911”, Isaac May, online image, Ancestry, (http:www.ancestry.com), accessed : 7 Apr. 2017.

Laurel County, Kentucky, Circuit Court Order Books, Criminal Order Book #14, 1911-1913, Commonwealth of Kentucky v General May, microfilm 7040453, Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.

“Mountain Desperado Hoped For Heaven”, Evansville Courier and Press (Evansville, Indiana), 10 Jul 1913, p. 8, digital image, Genealogy Bank.com (http://genealogybank.com : accessed 19 Jan 2017.

“Only Governor Can Save General May From Chair,” Courier-Journal (Kentucky), 29 Mar 1913, p. 7, column 6; digital image, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Louisville Courier Journal (1830-1992), ProQuest, (http://proquest.com: accessed 11 Apr 2017).

“Overdue At Eddyville,” Courier-Journal (Kentucky), 18 Mar 1911, p. 6, column 4; digital image, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Louisville Courier Journal (1830-1992), ProQuest, (http://proquest.com: accessed 11 Apr 2017.)

“Three To Be Executed At Eddyville In June,” Courier-Journal (Kentucky), 22 May 1913, p. 6, column 7; digital image, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Louisville Courier Journal (1869-1992), ProQuest, (http://proquest.com: accessed 11 Apr 2017.)

“Trial of Gen. May, Charged With Murder, Will Take All Week,” Courier-Journal (Kentucky), 15 Jun 1911, p. 2, column 6; digital image, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Louisville Courier Journal (1830-1992), ProQuest, (http://proquest.com: accessed 11 Apr 2017.)

“Two Men Killed In a General Fight On Otter Creek, Clay County.” Courier-Journal (Kentucky), 8 Jun 1900, p. 1, column 5; digital image, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Louisville Courier Journal (1830-1992), ProQuest, (http://proquest.com: accessed 11 Apr 2017.)

Walton, W. P., “Committed His Last Murder”, Lexington Herald (Lexington, Kentucky), 1 Jul 1913, vol.43, issue 182, p. 4, digital image, Genealogy Bank.com (http://genealogybank.com : accessed 19 Jan 2017.

[1] Hogan, Roseann Reinemuth, “Kentucky Ancestry A Guide to Genealogical and Historical Research” (Salt Lake City: Ancestry), 1992, pages 78-79.

[2]Kentucky, “Kentucky, Death Records, 1852-1964,” online database, Kentucky Statistics Original Death Certificates – Microfilm (1911-1964), Microfilm rolls #7016130-704803, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com : accessed 4/12/2017), entry for General May, 27 Jun 1913, Certificate #16508.

[3] Hogan, “Kentucky Ancestry”, pp 35-41

[4] 1900 U.S. census, Otter Creek, Clay County, Kentucky, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 0032, p. 103, sheet 7A,General May, FHL microfilm 12405516, digital image, Ancestry (http: www.ancestry.com), accessed: 7 Apr. 2017.

1880 U.S. census, Big Creek, Clay County, Kentucky, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 026, p. 568C, entry for General May, FHL microfilm 1254410, digital image, Ancestry (http: www.ancestry.com), accessed: 7 Apr. 2017.

[6] 1910 U.S. census, East Flat Lick, Knox County, Kentucky, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 0105, p. 1A, entry for General May, FHL microfilm 1374502, digital image, Ancestry (http: www.ancestry.com), accessed: 7 Apr. 2017.

[7] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 268.

[8] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 268.

[9] Kentucky, Corrections Cabinet, Register of Prisoners, 1848-1899, entry for General May, unpaginated, Kentucky State Penitentiary, Frankfort, microfilm 7009891, Kentucky Department For Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.

[10] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 297 and 514.

[11]Clay County, Kentucky, Marriage Certificate, p 604-605, General May-Louisa Hubbard, 29 Mar 1896; digital image, Kentucky, County Marriages, 1783-1965, Ancestry, (www.ancestry.com) accessed: 7 Apr 2017.

[12] 1900 Census

[13] “‘General’ Is Executed; Had Eight Significant Notches in Pistol,” Muskegon Chronicle (Michigan), 28 Jun 1913, p. 9, digital image, Genealogy Bank.com (http://genealogybank.com : accessed 19 Jan 2017.

[14] Walton, W. P., “Committed His Last Murder”, Lexington Herald (Lexington, Kentucky), 1 Jul 1913, vol.43, issue 182, p. 4, digital image, Genealogy Bank.com (http://genealogybank.com : accessed 19 Jan 2017.

[15] Bell County, Kentucky, Marriage Certificate, p 604-605, General May-Vina Mills, 7 Oct 1905; digital image, Kentucky, County Marriages, 1783-1965, Ancestry, (www.ancestry.com, accessed: 7 Apr 2017).

[16] 1910 Census

[17] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 512.

[18] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 515-516.

[19] 1920 U.S. census, Goose Rock, Clay County, Kentucky, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 54, p. 7B, entry for Cecie May, FHL microfilm T625_566, digital image, Ancestry (http: www.ancestry.com), accessed: 7 Apr. 2017.

[20] 1920 U.S. census, Salyersville, Magoffin County, Kentucky, population schedule, enumeration district (ED)68, p. 8B, entry for Basil May, FHL microfilm T625_589, digital image, Ancestry (http: www.ancestry.com), accessed: 7 Apr 2017.

[21]“Bloody Career of Kentucky Character Ends in the Eddyville Electric Chair”, Montgomery Advertiser

[22]“Bloody Career of Kentucky Character Ends in the Eddyville Electric Chair”, Montgomery Advertiser (Montgomery Alabama), 28 Jun 1913, vol. LXXXIV, issue 179, p. 5, digital image, Genealogy Bank.com (http://genealogybank.com : accessed 19 Jan 2017.

[23] “Committed His Last Murder”, Lexington Herald

[24] Betty Eddy. “General May Killings Were A Sensation In The Press”. Clay County Ancestral News Magazine, Fall & Winter 2008, Vol. 24, No. 2, p 2.

[25]Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 512.

[26] “Two Men Killed In a General Fight On Otter Creek, Clay County.” Courier-Journal (Kentucky), 8 Jun 1900, p. 1, column 5; digital image, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Louisville Courier Journal (1830-1992), ProQuest, (http://proquest.com: accessed 11 Apr 2017.)

[27] “‘General’ Is Executed; Had Eight Significant Notches in Pistol,” Muskegon Chronicle

[28] “General May Will Be Tried For Murder,” Courier-Journal (Kentucky), 17 May 1912, p. 2, column 6; digital image, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Louisville Courier Journal (1830-1992), ProQuest, (http://proquest.com: accessed 11 Apr 2017.)

[29] Betty Eddy. “General May Killings Were A Sensation In The Press”. Clay County Ancestral News Magazine, Fall & Winter 2008, Vol. 24, No. 2, p 39-40.

[30] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 272.

[31] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 272.

[32] “Bloody Career of Kentucky Character Ends in the Eddyville Electric Chair”, Montgomery Advertiser (Montgomery Alabama), 28 Jun 1913, vol. LXXXIV, issue 179, p. 5, digital image, Genealogy Bank.com (http://genealogybank.com : accessed 19 Jan 2017.

[33] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 272.

[34] A mattock is a tool similar to a pickaxe.

[35]Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 15-18.

[36] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 283-289.

[37] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 15-54.

[38] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 15-18.

[39] “General May is Caught,”, Lexington Herald (Lexington, Kentucky), 11 Mar 1911, issue 70, p. 4, digital image, Genealogy Bank.com (http://genealogybank.com : accessed 23 Feb 2017.

[40] “General May is Caught,”, Lexington Herald

[41] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 10, 15.

[42] “General May Taken To Richmond For Safekeeping,” Courier-Journal (Kentucky), 21 May 1911, p. 7, column 6; digital image, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Louisville Courier Journal (1830-1992), ProQuest, (http://proquest.com: accessed 11 Apr 2017).

[43] Clay County, Kentucky, Circuit Court Order Book 64. 1911, General May, Kentucky Department For Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky, p 536 & 637.

[44] Clay County, Kentucky, Circuit Court Order Book 64, p 611.

[45] “General May Must Die,” Courier-Journal (Kentucky), 25 Mar 1912, p. 3, column 4; digital image, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Louisville Courier Journal (1830-1992), ProQuest, (http://proquest.com: accessed 11 Apr 2017.)

[46] Kentucky, Court of Appeals

[47] Laurel County, Kentucky, Circuit Court Order Books, Criminal Order Book #14, 1911-1913, Commonwealth of Kentucky v General May, microfilm 7040453, Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.

[48] Laurel County, Kentucky, Circuit Court Order Books, Criminal Order Book #14, p 40.

[49] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 13.

[50] “Bloody Career of Kentucky Character Ends in the Eddyville Electric Chair”, Montgomery Advertise

[51] Betty Eddy. “General May Killings Were A Sensation In The Press”, p 19.

[52] Kentucky, Frankfort Penitentiary, Register of Prisoners, 1911-1936, entry for General May, 11 Jul 1911, unpaginated, microfilm 7009892, Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.

[53] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 6-7.

[54] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 1.

[55] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 26.

[56] Freeman will be used in lieu of the actual language that May used when referencing Farmer Freeman.

[57] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 32.

[58] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 44.

[59] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 40.

[60] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 69.

[61] Kentucky, Court of Appeals, p 69, 70.

[62] “Mountain Desperado Hoped For Heaven”, Evansville Courier and Press(Evansville, Indiana), 10 Jul 1913, p. 8, digital image, Genealogy Bank.com (http://genealogybank.com : accessed 19 Jan 2017.

[63] Betty Eddy. “General May Killings Were A Sensation In The Press”, p 40.

[64] Mountain Desperado Hoped For Heaven, Evansville Courier and Press

[65] Betty Eddy. “General May Killings Were A Sensation In The Press”, p 40.

[66] Betty Eddy. “General May Killings Were A Sensation In The Press”, p 40.

[67]Kentucky, Department of Corrections, Execution Records, file for General May, Eddyville State Penitentiary, Lyon County, Kentucky Department For Libraries and Archives.

[68] “Confession of Man Now Dead,” Lexington-Herald (Kentucky), 12 Jul 1913, p. 8, Genealogy Bank (http://www.genealogybank.com : accessed 11 Apr 2017.)

[69]Joyce Taylor Collins. “Meredith vs May”. Clay County Ancestral News Magazine, Fall & Winter 2008, Vol. 24, No. 2, p 37.

Fascinating! Farmer Freeman is my 2nd Great Grand Father. I and I doubt anyone else on my mother’s side of the family has every heard of this story. I am so grateful this research was done and want to thank all of those involved.

J.R. Higgins

burghcop@aol.com

Charles, It was so great to hear from your family! I would encourage you to visit the Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives and ask to see the court case files. They are very lengthy, but there is great testimony from Farmer Freeman, and he even outlines how his mother and General May’s mother were related, so there is a lot of family information inside!

Thanks for reading!

CD

This is amazing! My aunt has done a lot of research on this, but this article is painstakingly detailed. My grandfather was John Meredith(later changed to Meardy).Likewise my great-grandparents were Sherman and Belle. Thank you Linda Colston for this family treasure.

I deeply appreciate all of the work that was put in to this first and foremost. General has been brought up numerous times in the telling of our families violent history. I have always wanted to put a face to the man but have never had such luck. This story has helped me tremendously as an almost time capsule, putting me back in that period of his life. Thank you again.

Hello. I’d like to also offer my thanks for making this information available. Job very well done! My gggrandfather was Martin Butler (Britton) Smith, father-in-law to General May’s sister, Jane May. I’ve followed the lead in your article regarding General May having killed a “Mart Smith” in 1909 prior to the Meredith incident and have found this “Mart Smith” to have an interesting story in his own right with his connection to the White/Howard v Gerrard/Baker feud.

Mart Smith is said to have killed Deputy Bill Lewis in September of 1898 and is also said to have shot Deputy James Stubblefield a couple months before who, though papers reported to have died from his wounds which resulted in the amputation of his left arm and leg, later testified at the trial of Governor William Goebel’s assassination.

I have wondered if this Mart Smith was indeed my gggrandfather, MARTin Butler (Britton) SMITH. If so, General May killed his sister’s father-in-law for reasons I am yet unaware. Thanks again for your work. Well done.