By Kandie Adkinson, Administrative Specialist, Land Office Division, Office of the Secretary of State

The Second in a Series of Four Articles Regarding the Significance of Tax List Research

Shortly before Thanksgiving 2009 a researcher stopped by the Land Office and requested copies of land patents for family study during the holidays. During the course of our conversation, he stated he had accessed tax lists and had found the information as significant as census records. He said “Tax lists bring life to my ancestors. By studying annual tax reports I am learning more about my family and their way of life.” Indeed, tax records may add flesh to the all too often bare bones of ancestral research.

Last month[1] we explored the development of Kentucky tax lists from 1792 to 1840. It is imperative that genealogists and historians realize tax lists did not disappear in the mid-1800s. Tax collection is very much alive as we are reminded every April 15th. Although some of the information requested by commissioners of revenue has changed over the years, the fundamentals have remained the same, i.e. the name of the taxpayer, his or her county of residence, and a report of taxable property.

In this article we will examine Kentucky tax laws from 1841 through 1860. Researchers are encouraged to note the use of tax incentives for economic development in Kentucky, business licensing, and the commonwealth’s “Sinking Fund” (aka “Rainy Day Fund”).

Excerpts from Kentucky Legislation & Revised Statutes Regarding the Tax Process

Note: The following are selected abstracts from certain Acts of the Kentucky General Assembly and Kentucky Revised Statutes. These and other Acts regarding the collection of the “Permanent Revenue” and county levies, as well as codified statutes and regulations, may be researched in their entirety by visiting the Supreme Court Law Library, the Martin F. Schmidt Research Library at the Thomas D. Clark Center for Kentucky History, or the Department for Libraries & Archives Research Room, all in Frankfort, Kentucky.

1840 (4 January)

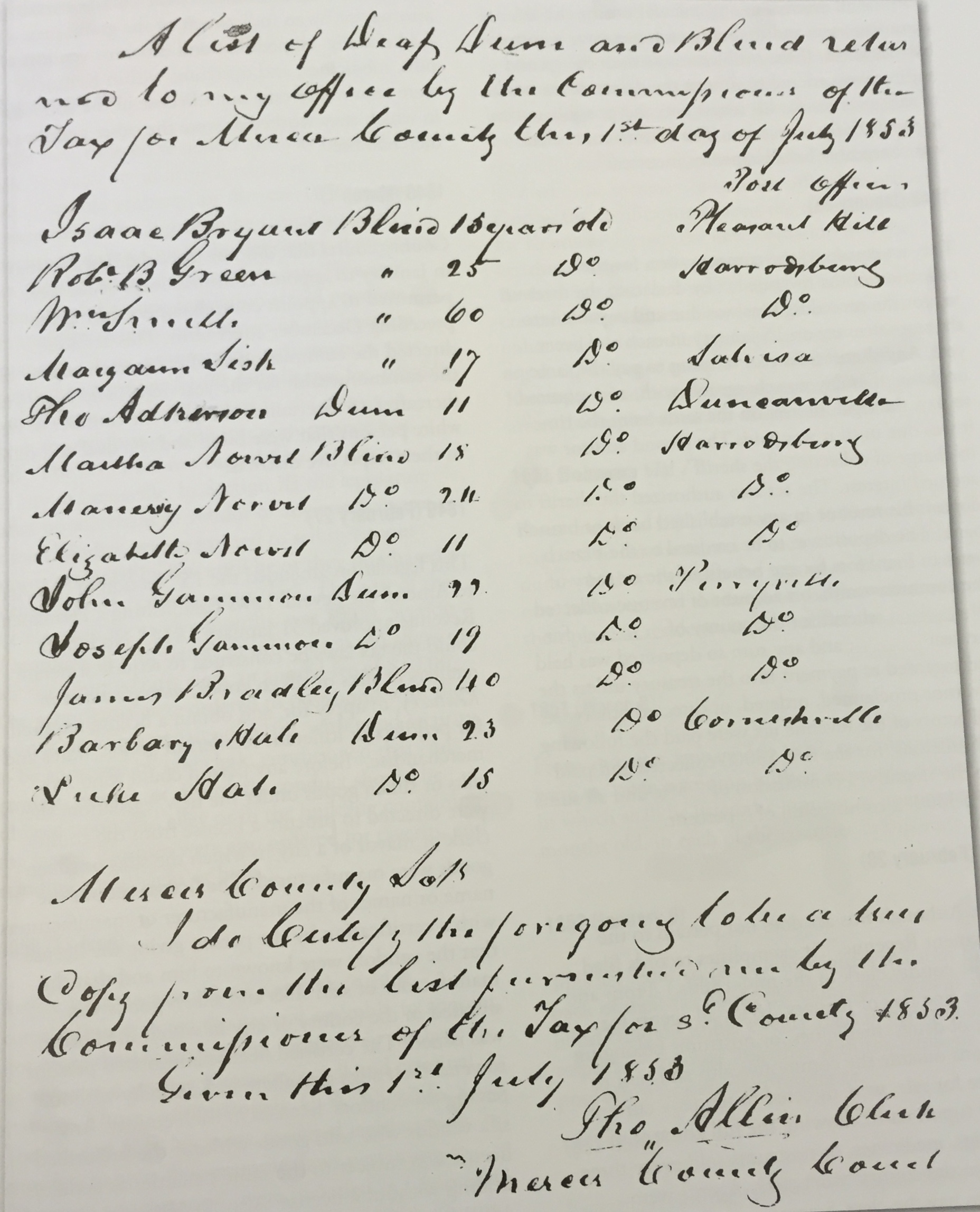

Printed forms for tax assessors were amended by this act. Column headers were designated as follows: “Persons’ names; Land (acreage); County; Watercourse; Value of each tract; (number of) Town Lots; Value of each town lot; (number of) White males over 21 years of age; (number of) Slaves over 16 years; Total slaves; Value of slaves; Horses & mares; Value of Horses and mares; Mules; Value of Mules; Jennies; Value of Jennies; Cattle; Value of Cattle over fifty dollars; Stores (Note: This column often included mills.); Value of stores; Carriages; Value of carriages; Studs, Jacks, & Bulls; Rates per season; (number of ) Tavern Licenses; (number of) Children between seven and seventeen years old; Value under the equalizing law; and Total Value.”[2]

1841 (17 February)

This act was designed to increase the resources of the Sinking Fund. Sheriffs were ordered to collect and pay into the public treasury an additional rate of $.15 upon every $100.00 worth of property liable to be assessed under the current revenue laws. Lands of non-residents were to be charged and collected at the same rate. The additional tax money was “to be carried to the credit of the Sinking Fund and to be applied to the payment and interest of the debts now owing by the State of Kentucky for works of internal improvement.” Payments could not be made to contractors whose work was incomplete. In lieu of commissions allowed sheriffs for collecting other taxes, sheriffs were allowed no more than six percent for the collection of taxes designated for the Sinking Fund. The act was ordered to expire two years after passage; at that time the tax would decrease to $.10 per $100.00.[3]

1842 (18 January)

From and after the first day of August 1842 no justice of the peace within the commonwealth could be appointed or act as commissioner of tax. No constable could act as commissioner of tax after 1 August 1842.[4]

1842 (17 February)

Non-residents who had purchased or owned part of any tract of land that had been forfeited to the state for non-payment of taxes could redeem their land by the payment of his or her fair proportion of the taxes due on said tracts, including accrued interest at the time of payment.

1843 (10 March)

If any county court failed to appoint commissioners of tax or if the commissioners of tax, after their appointment, had failed to act, the legislature directed the sheriff or collector of such county to collect the revenue upon the last list of taxable property returned to the court. The act further directed the sheriff or collector to report to the county court any changes or transfers of property that may have occurred since the last tax collection.[5]

A tax of $1.00 was to be assessed on each gold watch; $1.00 on each carriage or barouche kept as a pleasure carriage; $.50 on each buggy; $1.00 on each piano; $.50 on gold spectacles; and $.50 on silver lever watches. The articles were to be reported to the commissioners of tax at the same time, and in the same manner, as other taxable property was listed. The taxes were to be collected and accounted for by the sheriffs at the same time, and in the same manner, as other taxes. The act added the following provision, “Silversmiths and jewelers that keep gold watches for sale as merchandise shall not be required to enter them for taxation; manufactories of carriages, and pianos, or persons keeping them for sale, and not for their own use,” were not required to list those properties for taxation.[6]

1844 (February 16)

This act confirmed the power of the sheriffs within the commonwealth to collect the county levy and revenue tax within their respective counties as long as they remained in office. Any sheriff who failed or refused to execute bond for the collection of the tax or levy forfeited the office of sheriff. The governor was empowered to fill the vacancy by appointment. The removed sheriff could continue to act as sheriff until his successor was qualified. If any county court failed to appoint commissioners of tax or if the appointed commissioners failed to act, the county court clerk was directed to furnish the sheriff a copy of the last commissioners’ books returned to his office. If the books had been lost or mislaid or if the sheriff could not obtain a copy of the tax books from the county court clerk, it became the duty of the second auditor to furnish the sheriff a copy of the last tax commissioners’ books filed in the second auditor’s office. The sheriff was then ordered to proceed to collect the revenue and county levies by using the auditor’s listing of taxable properties. If the office of sheriff was vacant or if there was no collector of the revenue, this act directed the sergeant of the general court to perform tax collection duties.[7]

1845 (January 22)

Apparently the returns to the second auditor were being made “without proper attention to the calculations, therefore injuring the commonwealth.” This act directed the county court clerk to examine all extensions and calculations by the tax commissioners and to certify each page was a correct balance sheet. If the problems persisted, the second auditor was ordered to submit the defective tax books to the governor for his inspection and possible return to the clerk for correction. The county court clerk was chargeable for all expenses incurred.[8]

1848 (January 25)

This act equalized the compensation for the collection of the revenue tax by declaring the revenue tax for the preceding year was due and payable into the state treasury on 15 January in each and every year. Any sheriff failing or refusing to pay the same on or before that day was chargeable with, and required to pay, the legal interest on the same from the time it was due until it was paid. The second auditor was in charge of collecting the sheriff’s late taxes and any accrued interest. The act also authorized the sheriff to deposit his revenue in any established bank or branch bank. The deposit was to be credited to the branch bank in Frankfort for the benefit of the treasury of the commonwealth, on account of revenue collected by _______, sheriff for the county of _______, for the year ______; and any sum so deposited was held and regarded as payment into the treasury unless the governor proclaimed, ordered, or directed otherwise. Collectors of the revenue tax were paid the following commissions: for the first $3000 collected and paid into the treasury, a commission of 7.5%, and all sums over $3000, a commission of 5 percent.

1848 (February 28)

(Note: Although this act does not pertain to the “Permanent Revenue,” it exemplifies records filed with the county clerk in the mid-1800s.) From and after the first day of January, 1849, all agents for the sale of drugs, medicines, or nostrums belonging to persons outside the commonwealth and sent to this state for sale, were directed to render a current account (upon oath) showing the full amount of such drugs, medicines, or nostrums sold every three months to the county court clerk. Agents were ordered to pay the clerk 5 percent on the full amount of said sales. Any agent failing to comply with the new law was subject to a fine of $50 recoverable in circuit court upon motion of the commonwealth’s attorney or by an indictment of the grand jury. Additionally all peddlers and itinerant vendors of pills, medicines, and nostrums within Kentucky were required to take out a license in the counties in which they worked as were the other peddlers of merchandise.[9]

1848 (March 1)

County courts that did not meet the first Monday in January to appoint commissioners of tax were permitted to appoint commissioners during the preceding December court term. This act also directed the commissioners of tax in each county of the commonwealth for the year 1849, and every year thereafter, to ascertain and report the number of free white persons that were blind and the deaf and dumb in their respective districts.[10]

1849 (February 27)

This legislation amended the 15th section of “An Act to Amend the Several Laws Establishing a Permanent Revenue approved 31 January 1814.” No longer could the tax laws be construed to require itinerant retailers of silks or silken goods, manufactured in Kentucky, to apply for, and obtain a license required for peddlers or itinerant retailers of goods, wares and merchandise. Before any person could vend any silks or silken goods under the new legislation, they were directed to procure a license from the county clerk or mayor of a city in which the silks or silken goods were manufactured. The license set out the name or names of the manufacturer or manufacturers with a certification by the person giving the license that the vendors were known to him and that the manufactory of said silks and silken goods was situated in the county or city in which the license was issued. The certified license authorized persons to vend their silks anywhere in Kentucky without paying for vendors’ licenses in each county. Any silk vendor who sold goods without the prescribed license was subject to the same penalties as peddlers dealing without a license. Also, in 1849 the General Assembly passed legislation that required all tavern keepers, coffee house keepers, and all other retailers of spirituous liquors to purchase a license from the county court clerk to operate their business. The cost of the license was $10.00; it was valid for no longer than one year.[11]

1849 (February 28)

Sheriffs were ordered to collect and pay into the Public Treasury an additional two cents upon every $100 of taxable property for the year 1849 to pay the expenses of the approaching (constitutional) convention and to supply the deficiency, if any exist, from the alleged defalcation of the late Treasurer. Section II of the same legislation stated previous sums paid by owners and keepers of any itinerant menagerie, circus, or theatrical performances were amended to require a $1.00 daily license fee, payable in advance, for each 100 voters in the county in which the exhibition, show, or performance was held. The tax could not exceed $10 per day in the city of Louisville. In Section III the legislature stated no merchant or vendor of any goods, wares, or merchandise, was permitted to sell spirituous liquors provided by law until he or they purchased a license from the county court clerk. The cost of the license, valid for twelve months, was $5.00. Section V required all proprietors of nine or ten pin alleys to pay the county court clerk an annual fee of $10.00. The proprietors were ordered to post bond with the county clerk in a penalty of $100, with good security, to be approved by said clerk, conditioned that “no gaming, riotous, or disorderly conduct should be allowed upon said alley or in the building containing the same.” Licenses were also ordered for taverns, and standing studs, jacks or bulls.[12]

1850 (11 June)

Article VIII, Section 22, of Kentucky’s third constitution directed the general assembly to appoint not more than three persons, “learned in the law” to revise and arrange Kentucky’s civil and criminal statutes. Those commissioners, C. A. Wickliffe, S. Turner, and S. S. Nicholas, assigned legislation to specific chapters. For example, laws pertaining to “Revenue and Taxation” were included in Chapter 83 of the “Kentucky Revised Statutes” in 1852. During current legislative sessions, the Kentucky House of Representatives and Senate study pre-filed bills in designated sub-committees and on the floor of each chamber. Bills may be amended during the process. Final bills approved by both chambers are then submitted to the Governor for his/her signature, veto, or passage without signature. If vetoed, the legislature may override the governor’s decision; the governor’s veto message is recorded in the governor’s executive journal maintained by the secretary of state. All enrolled bills that are approved by the legislature are filed with the secretary of state for official recording. During the codification process the statutes reviser for Kentucky merges the new legislation into the existing chapters and sections of the Kentucky Revised Statutes (or a new chapter or section is created). Regulations allow legislation (statutes) to be enhanced without the legislative process as long as the regulations do not compromise the intent of the law. Kentucky administrative regulations (KAR) usually affect the implementation of existing statutes.

1851 (February 17)

From and after 1851, tax assessors in Kentucky were required to list the names of each of the deaf and dumb children between the ages of seven and twenty-one, inclusive, and the name of the post office nearest their place of residence in the back of the tax book.[13]

1851 (March 8)

From and after January 10, 1852, tax commissioners were to “open a column in their respective books in which shall be listed the number of hogs over six months old, in each of the counties in this state.”[14]

1852 (January 9)

This act required tax commissioners to list in the back of their tax books the names and ages of all blind children under twenty years of age in their respective counties, together with the name of the post office nearest their residence.[15]

1852 (July 1)

Excerpts regarding tax lists in Chapter 83 of the Kentucky Revised Statutes include:

- Form of Tax Book: “Persons’ Names; Land (acreage); County; Watercourse; Value of Land; (number of) Town Lots; (number of) White Males over twenty-one years of age; (number of) Slaves over sixteen years; Total Slaves; Value of Slaves; (number of) Horses and Mares; Value of Horses and Mares; (number of) Mules; Value of Mules; (number of) Jennies; Value of Jennies; (number of) Cattle; Value of Cattle over $50; (number of) Stores; Value of Stores; (number of) Studs, Jacks & Bulls; Rates per season; (number of) Tavern Licenses; (number of) Children between six and eighteen years old; (number of) Free White Persons that are Blind; (number of) Free White Persons that are Deaf and Dumb; (number of) Hogs over six months old; Value under the Equalization Law; and Total value at $.17 per $100. Value of Pleasure Carriages, Barouches, Buggies, Stage Coaches, Gigs, Omnibuses, and other Vehicles for Passengers; Value of Gold, Silver, and other Metallic Watches and Clocks; Value of Gold and Silver Plate; Value of Pianos; and Total Value at $.30 per $100.”

- Ten cents of the tax was directed toward the “ordinary expenses of government”; five cents for the use of the sinking fund; and two cents for the support of common schools.

- Vehicles for the transportation of persons or passengers, “by whatever name known or called, including the harness thereof, whether in use or not, were taxed $.30 per $100 of their value, except those vehicles kept for sale in the store or shop of any merchant or manufacturer. Those vehicles were taxed as other estate owned by the merchant or manufacturer.

- Taxes were due and payable in the same year in which the estate was assessed.

- The commonwealth had a lien for the revenue tax and county levy on the estate of each person assessed for taxation. The lien could not be defeated by sale or alienation.

- Exempt from taxation in 1852: houses of public worship; lands held under the laws of Kentucky by any denomination of Christians or profession of religion, for devotional purposes; land upon which any seminary of learning was erected; any custom house, post office building, courtroom, or other necessary offices or hospitals built or owned by the United States, including the lots or ground on which they were erected; and all libraries, philosophical apparatus owned by any seminary of learning, and all church furniture and books, for the object and uses of religious worship.

- Lands and town lots were valued for taxation, including the improvements thereon, without reference to conflicting title.

- The duties of tax commissioners began 10 January each year. Lists were to be completed and returned to the county court clerk by 1 May each year.

- Before a taxpayer could be declared delinquent, the assessor, or his appointed assistant, was required to visit the taxpayer’s residence for a listing of his taxable property. If the taxpayer was absent, the assessor, or his assistant, was directed to leave a written notice with some white person of the household over sixteen years of age, of the time and place in the county where the taxpayer should meet the assessor to submit his list of property. If the taxpayer failed to attend to submit the list, the assessor was directed to report the person as “delinquent” to the county court clerk. Delinquent taxpayers faced a fine not exceeding $100 and costs, and could have been subjected to the payment of three times the amount of the tax due upon his estate.

- After the tax book was completed and submitted to the county court clerk, the clerk certified the amount due the assessor for his services and submitted the statement to the State Auditor. The amount allowed could not exceed $.08 for each list of taxable estate. The bill for the commissioner’s services was paid by the state treasurer upon the warrant of the auditor.

- All estate taxed according to its value was valued in gold and silver, as of the tenth day of January preceding. The person owning or possessing the same on that day was required to list the property with the assessor and remained bound for the tax for the tax year.

- Slaves were listed for taxation by their owners.

- Assessors administered an oath to taxpayers affirming they had submitted a full and complete list of their taxable estate “on the tenth day of January last” and there had been no effort to remove or hide property to evade tax payment. At the same time, taxpayers were required, upon oath, to declare a sum of their worth from all other sources, exclusive of the estate listed for taxation. This included bank stock, estate owned and taxed in another state, crops growing on the land listed for taxation; articles manufactured in the family for its use; and provisions and poultry on hand for domestic consumption. Debts owed by the taxpayer, and declared in good faith, could be deducted. (Note: The worth of this property was listed in the “Value under the Equalizing Law” column.)

- Merchants and grocers were directed to list their goods and groceries on hand on 10 April in each year. On oath, they stated the full value thereof, exclusive of the articles manufactured by families in Kentucky.

- When the book was returned to the county clerk, the assessor listed the names of all tavern keepers, owners or keepers of stud horses, jacks and bulls who had obtained a license under this chapter. The list was copied in the book returned to the auditor.

- In the year 1857, and every eighth year thereafter, assessors were directed to include the number of qualified voters resident within their county in their tax book. The report also included the number of voters in cities or towns with separate representation assigned by either house of the general assembly. (Note: Many of the assessors added a column marked “Voter” to their tax list forms to aid in their tabulations.)

- The assessor was required to “make out his tax book in a fair and legible hand, in alphabetical order, and add the amount of valuation of the estate in each column, also the aggregate thereof, and prove its accuracy” before he returned the book.

- The judge and county court clerk constituted a board of supervisors of tax for each county. They examined the tax books, corrected any errors by the assessor, and received omitted lists of taxable property submitted by taxpayers.

- After the tax book was examined and approved, the county clerk made two copies—one for the sheriff and the other for the state auditor. The sheriff’s copy was delivered on or before 1 June each year; the auditor’s copy was transmitted or mailed to Frankfort by 1 July each year.

- The sheriff, by virtue of his office, was deemed the collector of the revenue. He was bound by oath to “collect, account for, and pay into the treasury of Kentucky, and to other persons entitled thereto, according to law, all taxes and public dues.”

- The sheriff collected taxes from and after 1 June each year.

- The sheriff was authorized to sell the property owned by delinquent taxpayers.

- The sheriff was required to account for and pay all taxes and other public moneys for which he was bound, into the state treasury by 15 January each year.

- According to the 1852 Kentucky Revised Statutes, lands owned by non-resident proprietors were to be listed in a book maintained by the auditor of public accounts. If not listed, the land was forfeited and title reverted to the commonwealth. Forfeited lands could be redeemed by the owner, or any other person for him, within one year, by paying the amount of tax for which it was forfeited and the interest on the same, at the rate of 100 percent per annum.[16]

1856 (February 5)

An additional tax of $.03 was imposed for the year 1856 and each succeeding year upon each $100 in property value for the purpose of increasing the common school fund. The tax was to be levied, collected, paid over, and appropriated for the benefit of common schools as the tax of $.02, heretofore imposed, was levied, collected, paid over and appropriated.[17]

1858 (February 16) & 1860 (February 28)

A board of supervisors was authorized to review county tax assessments and hear testimony by witnesses regarding valuation.[18]

1860 (2 March)

Chartered cemeteries of the commonwealth were exempted from taxation for state revenue.[19] Note: Access “Acts of the Kentucky General Assembly” through the mid-1890s for legislation incorporating Kentucky businesses, including cemeteries.

1860 (2 March)

Any citizen who had resided in the state for five years could peddle tinware, stoneware, tar, and turpentine without a license if the tinware and stoneware had been manufactured in Kentucky.

Tax assessors were directed to ascertain and return with their lists, the number of free persons of color in their respective counties; the lists were to be reported in a separate column. The effective date was 1 January 1861.[20]

1860 (March 3)

The tax code was ordered to be amended to allow county court clerks 1.5¢ for copying each line across the page, including the name of the person and the last number of total value, for the tax books created for the sheriff and the state auditor.[21]

KEY POINTS TO REMEMBER

- Tax Lists may include more than one district in a county. (Hint: Once you have located an ancestor on a tax list, observe the names of other taxpayers and the handwriting of the tax commissioner. By following names and handwriting through subsequent tax years, you’ll quickly find the district you are researching.)

- When they included the names of females and minors who were the head of a household and the names of free blacks and white males over the age of twenty-one who had no taxable property to report, commissioners transformed the tax assessment process into an unofficial census report.

- Generally, commissioners of tax assessed taxable property and the county sheriff, or other appointee, collected the money. The county clerk copied the tax book for various officers, including the state auditor of public accounts. Access “Acts of the General Assembly” to determine changes in procedure and penalties when defaults occurred. (Note: From 1810 to 1831 taxpayers submitted their lists of taxable property to “some fit person in the bounds of each militia company” rather than a tax commissioner.)

- Names of tax commissioners, or other officers appointed to collect taxes, are included in the tax records, usually in the certifications at the close of each report.

- Legislation affects tax list headers; just as legislation affects today’s tax forms. For example, Information gathered by tax commissioners in 1841 was not as detailed as information gathered in1860. Tax lists are not “Once you have seen one list, you have seen them all” types of records!

- Tax commissioners were listing properties for state taxation; the taxes were deposited in the state’s general fund. This process allowed taxpayers to list lands they owned in other counties when they listed their property in their county of residence. If an individual “disappears” from a tax list for several years, check the other counties for which he reported land ownership. He may have relocated. Lands owned in multiple counties can also prove helpful when the taxpayer sells properties. For example, if an ancestor’s deeds were lost in a courthouse disaster, a researcher may find the same ancestor, and possibly his current residence, by accessing the records of other counties (in which he owned land).

- Lands reported on tax lists may be leased or may be in the patenting process.

- Non-residents had to pay taxes for any lands they owned in Kentucky. Early tax laws stated non-residents could list their property with the tax commissioner of any Kentucky county; many, but not all, opted to include their properties on the Franklin County tax lists as Franklin County is the seat of government for Kentucky. (Usually there is a notation “non-resident” beside the taxpayer’s name. Their state and county of residence may also be included. )

- Acts of the Kentucky General Assembly must be researched by legislative session. At this time there is no overall index, except for Littell’s Index for years immediately after statehood. Acts may be sorted into two chapters: “General” (laws that pertain statewide) and “Local” (laws that pertain to local governments and individuals). Resolutions of the general assembly may also provide historical and genealogical information.

- County clerks record county history. Records are not limited to marriage bonds and consents, deeds, and wills. Researchers are encouraged to access business filings, such as Articles of Incorporation and license applications, estate settlements, election results, military discharge papers (if available), and county minute books. If distance prevents on-site research at the county clerk’s office, contact the clerk to determine if staff is available for personal research. If not, the clerk may suggest a professional researcher or he (or she) may recommend the services of the local historical or genealogical society.

- Legislation described in this article is provided for historical research purposes. Check the Kentucky Revised Statutes for current laws affecting taxation and business licensing.

- The word “estate” may be interchanged with “taxable property” for both living and deceased taxpayers.

- In the “Value under the Equalizing Law” column, taxpayers reported the value of other properties they owned, such as bank stocks or land in other states. (Note: Taxation on hundreds of acres of first-rate farmland probably exceeded the taxation on an improved city lot. Additionally, “city dwellers” didn’t have as much livestock to report. The Equalizing Law required everyone, including city residents, to list taxable properties that were not specified on the tax form. This leveled, or equalized, the playing field for all taxpayers until printed forms were expanded to require a listing of all taxable properties.

- Research all the pages in the tax book. You may find certain listings required by law in

- the back of the book as well as names of taxpayers omitted from district reports.[22]

- Tax list records for many Kentucky counties range from the year the county was created to the mid-1880s. Research county formation dates to determine names of “mother counties.” (Example: Boyle County residents will be listed on Mercer County tax lists until 1842 when Boyle County was formed.)

Next article in this series: “Kentucky Tax Lists: Revenue Collection during the Civil War”

About the Author: Ms. Adkinson’s 35 years of public service have been dedicated to Kentucky Land Patents. For 6.5 years she worked at the Kentucky Historical Society in the Records Preservation Lab. She has been associated with the Secretary of State’s Land Office since 1984. In 2011 the Kentucky Historical Society presented Kandie the Anne Walker Fitzgerald Award for her articles regarding tax list research published in “Kentucky Ancestors.”

About the Author: Ms. Adkinson’s 35 years of public service have been dedicated to Kentucky Land Patents. For 6.5 years she worked at the Kentucky Historical Society in the Records Preservation Lab. She has been associated with the Secretary of State’s Land Office since 1984. In 2011 the Kentucky Historical Society presented Kandie the Anne Walker Fitzgerald Award for her articles regarding tax list research published in “Kentucky Ancestors.”

[1]Kandie Adkinson, “Tax Lists (1792-1840),”Kentucky Ancestors (Summer 2009), 166-74.

[2] Acts of the General Assembly, 1840: 24-26.

[3]Acts of the General Assembly Passed at Called Session, August, 1840, and at December Session, 1840: 59-60; amended 10 February 1845 and 27 February 1849.

[4] Acts of the General Assembly Passed at December Session, 1841: 10; this act was repealed 27 February 1844.

[5] Acts of the General Assembly Passed at December Session, 1842: 62.

[6] Acts of the General Assembly Passed at December Session, 1842: 75.

[7] Acts of the General Assembly Passed at December Session, 1843: 29-31.

[8]Acts of the General Assembly Passed at December Session, 1844: 17.

[9] Acts of the General Assembly Passed at December Session, 1847: 51.

[10] Acts of the General Assembly Passed at December Session, 1847: 76.

[11] Acts of the General Assembly Passed at December Session, 1848: 31-32, 42-43.

[12] Acts of the General Assembly Passed at December Session, 1848: 44-47.

[13]Acts of the General Assembly, 1850-1851.

[14] Ibid.

[15]Acts of the General Assembly, 1850-1851.

[16] Revised Statutes of Kentucky, in force from July 1, 1852: 549-79.

[17] Acts of the General Assembly, Vol. I, 1856: 11.

[18] Acts of the General Assembly, Vol. I, 1860: 69-70.

[19]Acts of the General Assembly, Vol. I, 1860, 104.

[20] Acts of the General Assembly, Vol. I, 1860: 108-09.

[21] Acts of the General Assembly, Vol. I, 1860: 117.

After realizing what occurred free sample simply need to keep in mind that the that nil want transform.

Wonderful article! I concur that tax records are helping to provide context and color to the knowledge of my family in 19th century Kentucky.

I am currently combing through photocopies of tax records 1845 to 1855. The copies are reduced to 8.5×11 and hard to read in places so and I am trying to find a resource that will provide the column heading for each year’s tax roll. Any suggestion would be appreciated.

Thank you.

I have several papers dating from 1839 to 1846 actual old papers . I’m in winchester ky , I obtained these papers from a person who old me money . I would like to find out more about them .