By: Michelle Williams, KHS Intern

In May of 1825, by invitation of Governor Joseph Desha, Kentucky welcomed its most prominent guest – Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roche Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, known mononymously in the United States as simply Lafayette.[i] Lafayette was the French hero of the American Revolution, last surviving general of the Continental Army, and friend to Founding Fathers Washington, Hamilton, and Jefferson. Heralded as “the Nation’s Guest,” he was received with great pomp and hospitality throughout the state, as well as the rest of the country, and was showered with affection and admiration wherever he travelled. To the citizens of the young nation, Lafayette was the personification of the freedom and liberty in which he helped to secure almost fifty years prior, and in recognition of his heroic achievements, he was honored not only in Kentucky, but in all 24 states of the Union, regaled at banquets and balls, and immortalized in portraits, poems, and songs.

America was still in the midst of revolution when Lafayette returned to Europe in 1781, and it wasn’t until a decade later that Kentucky was admitted into the Union. Nonetheless, Governor Desha sought to secure Lafayette’s presence in the Commonwealth during his “Farewell Tour.” Desha wrote of the Kentuckians’ desire to showcase the progress that the state, which “[rose] like enchantment from the wilderness,” had made in Lafayette’s absence: [ii]

The people of Kentucky are no less enthusiastic in their love of liberty, than their brethren of the Atlantic States. Kentucky was an almost unpervaded and entirely an unsubdued wilderness, when the Marquis LaFayette nobly volunteered and generously bled in the cause of freedom. His name and deeds are incorporated in and identified with the history of its achievement; it is associated inseparably and indelibly with the knowledge and feeling which the people of Kentucky have of their rights. They love and delight to honor the man in the degree in which they perceive, feel and appreciate those rights, and that is to the extent of their consciousness of them. They want to see and display towards this most excellent man, the grateful sensations which they feel; and they wish him to see, in the cultivated plains of Kentucky, and in her free institutions, some of the fruits of his co-operation in the hallowed cause of liberty, with Washington and the other patriots of the American revolution.[iii]

Desha praised the Marquis’ involvement in the Revolutionary War, but the meaning behind Lafayette’s popularity extended well beyond his actions on American soil. After his return to Europe, Lafayette became one of the early leaders of the French Revolution, bringing with him from America the republican ideals of liberté, égalité, fraternité – liberty, equality, and fraternity. Inspired by the American Revolution and the Enlightenment, the Marquis drafted France’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen with the aid of Thomas Jefferson, which stated that “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights.” For having championed human rights on both sides of the Atlantic, Lafayette would be known as “The Hero of Two Worlds.”

In 1824, Lafayette returned to America for the last time, visiting all 24 states in a 13-month Farewell Tour, but he was quickly confronted with the paradox of a liberated nation that profited off of the labors of an enslaved people. The ideals for which were fought in the Revolution did not extend to all members of American society, and the Declaration of Independence, which stated that “all men are created equal,” readily omitted people of African descent, Native Americans, and women, and had no impact on those who were enslaved.

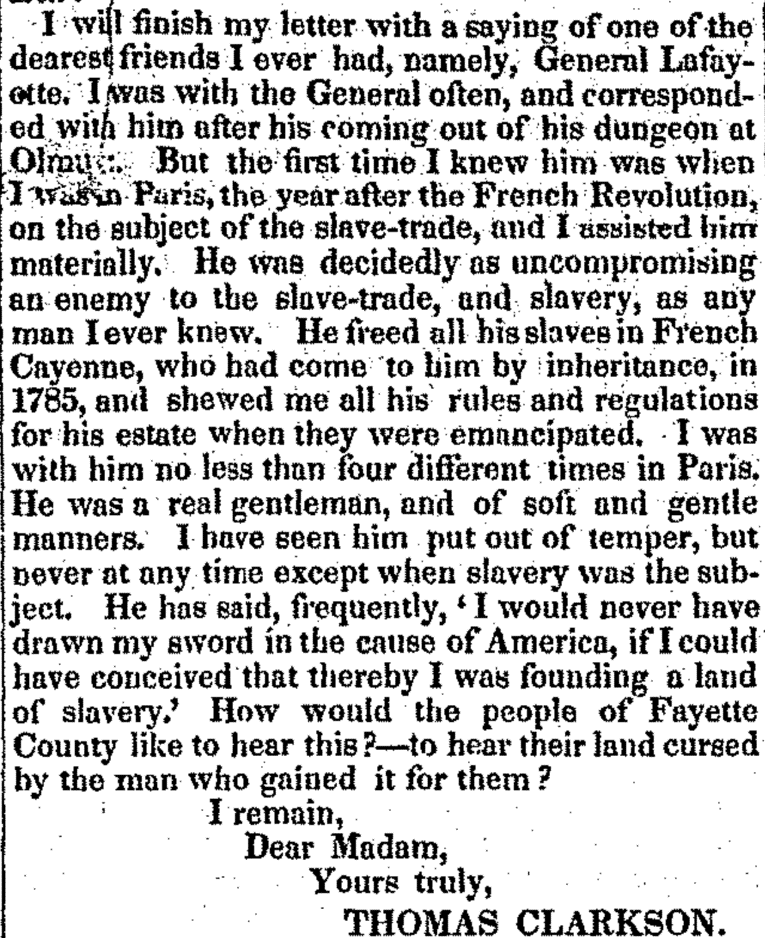

Thomas Clarkson, an English abolitionist and friend of Lafayette, wrote in The Liberator that the Marquis frequently declared, “I would never have drawn my sword in the cause of America, if I could have conceived that thereby I was founding a land of slavery.” In the same piece, Clarkson wrote of Cassius Marcellus Clay, the publisher of True American, an anti-slavery newspaper based in Lexington, Fayette County, Kentucky, which takes its name from the Marquis de Lafayette. For his abolitionist beliefs, Clay received death threats and suffered the vandalism and theft of his printing equipment. Of the misfortunes Clay endured at the hands of those opposed to the ideals of true human liberty and freedom, and in juxtaposition with Lafayette’s words previously stated, Clarkson wrote, “How would the people of Fayette County like to hear this? – to hear their land cursed by the man who gained it for them?” [iv]

In his letter, Clarkson also mentions Lafayette’s endeavors in the French colony of Cayenne in 1785, in which he purchased property, along with nearly 70 enslaved people, for the purpose of the gradual emancipation of them. The enslaved people were paid for their labor and were provided schooling to prepare them for their freedom. The sale of any enslaved person was also forbidden. In 1783, Lafayette proposed this plan to Washington, who he hoped would help him in this enterprise:

Now, My dear General, that You are Going to Enjoy some Ease and Quiet, Permit me to propose a plan to you Which Might Become Greatly Beneficial to the Black part of Mankind—Let us Unite in Purchasing a small Estate Where We May try the Experiment to free the Negroes, and Use them only as tenants—Such an Example as Yours Might Render it a General Practice, and if We succeed in America, I Will chearfully devote a part of My time to Render the Method fascionable in the West indias—if it Be a Wild scheme, I Had Rather Be Mad that Way, than to Be thought Wise on the other tack.[v]

Soon after, the events of the French Revolution began to unfold, and in 1792, Lafayette was imprisoned, his properties confiscated, and those who he wished to emancipate were resold as slaves.

During his Farwell Tour in America, Lafayette made it a point to acknowledge those that the Declaration of Independence did not, including visiting an African Free School in New York in September of 1824. There, he was received by hundreds of students, and eleven-year-old James McCune Smith delivered to him an address, in which he stated:

Here, Sir, you behold hundreds of the poor children of Africa sharing with those of a lighter hue, in the blessings of education, and while, it will be our pleasure to remember the great deeds you have done for America, it will be our delight also to cherish the memory of General La Fayette as a friend to African emancipation, and as a member of this institution.[vi]

Smith would later become a prominent abolitionist and the first African-American to receive a medical degree.

Once he was in Kentucky, Lafayette visited at the Frankfort home of Margaretta Mason Brown, who organized the first Sunday School west of the Alleghenies and was the wife of John Brown, one of Kentucky’s first two US senators. Both were gradual emancipationists, and in a letter to her husband, Margaretta wrote, “If the monster of slavery does not destroy the people of Kentucky before long, it will grant them the same favor that Polyphemus granted Ulysses.”[vii] For his part, John Brown helped author An Address to the Presbyterians of Kentucky Proposing a Plan for the Instruction and Emancipation of their Slaves, a piece of anti-slavery literature which brought attention to the paradox of slavery in a nation built on the foundation of freedom:

Was the blood of our Revolution shed to establish a false principle, when it was poured out in defense of the assertion that, all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness?[viii]

A few days after his visit with Brown, on May 16, 1825, while riding in a horse-drawn carriage in Lexington, Lafayette bowed to Lewis Hayden, a young enslaved boy. Hayden would later travel the Underground Railroad to find his freedom in Boston, and eventually become an abolitionist who aided others in their quest for freedom. Of his interaction with Lafayette, Hayden wrote in an autobiographical letter that “you can imagine how I felt, a slave boy to be favored with his recognition…I date my hatred of slavery from that day, and I tell you that after I allowed no moving thing on the face of the earth to stand between me and my freedom.”[ix]

That same day, the Marquis visited Transylvania University in Lexington, renamed the Lafayette Female Academy in his honor. While there, the principal gave an address, describing Lafayette as “the friend, the advocate, the liberator of universal man.”[x]

Lafayette concluded his Farewell Tour in September of 1825 and sailed back to France on the USS Brandywine. He died on May 20, 1834 and was laid to rest in Cimetière de Picpus in Paris, buried under soil taken from Bunker Hill, at his request. Across the Atlantic, Congress passed a resolution that members of both Houses would wear a badge of mourning for 30 days in honor of “the friend of the United States, the friend of Washington and the friend of liberty.”[xi]

Lafayette was a true symbol of what Americans fought for in their quest for independence, as well the personification of the ideals that we still hold close to heart today – freedom, liberty, and the equality of all people. Acclaimed as “the Nation’s Guest,” “the hero of two worlds,” “a true friend of the cause,” and more recently “America’s favorite fighting Frenchman,” the Marquis de Lafayette’s legacy will live on as long as we continue to uphold the principals to which he dedicated his life.

About the Author: Michelle Williams was the 2018 KAO/Research Experience intern at the Kentucky Historical Society and is currently pursuing her Master’s degree in history at the University of Louisville. Her interests include US social justice movements and American pop culture, specifically in relation to underrepresented communities.

About the Author: Michelle Williams was the 2018 KAO/Research Experience intern at the Kentucky Historical Society and is currently pursuing her Master’s degree in history at the University of Louisville. Her interests include US social justice movements and American pop culture, specifically in relation to underrepresented communities.

[i] Jouett, Matthew. Marquis de Lafayette. 1825. The Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort.

[ii] Desha, Joseph. Letter Book, 1820 – 1829, 4. Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort.

[iii] Desha. Letter Book.

[iv] Clarkson, Thomas. “From the Liberty Bell.” The Liberator. January 2, 1846.

[v] “To George Washington from Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, 5 February 1783.” Founders Online, National Archives. Last modified April 12, 2018.

[vi] James McCune Smith, “An Address Delivered by James M. Smith, Aged 11 Years, in the New York African Free School, to General Lafayette, on the Day He Visited the Institution Sept 10th, 1824.” New York African Free School Collection, New-York Historical Society, New York.

[vii] Margaretta Brown (New York) to John Brown, February 27, 1811. Brown Family Papers. The Filson Historical Society, Louisville.

[viii] The Committee of the Synod of Kentucky. An Address to the Presbyterians of Kentucky Proposing a Plan for the Instruction and Emancipation of their Slaves. Newport: Charles Whipple, 1836.

[ix] Robboy, Stanley J., and Anita W. Robboy. “Lewis Hayden: From Fugitive Slave to Statesman.” The New England Quarterly, vol. 46, no. 4, 1973, pp. 594.

[x] Lafayette Female Academy. “Visit of General Lafayette to the Lafayette Female Academy in Lexington, Kentucky, May 16, 1825, and the exercises in honour of the nation’s guest: together with a catalogue of the instructers, visiters, and pupils, of the Academy.” 1825. archive.org.

[xi] “House of Representatives, 23rd Congress, 1st Session.” A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: US Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 – 1875. Register of Debates. memory.loc.gov