By Kandie Adkinson, Administrative Specialist, Land Office Division, Office of the Secretary of State

Editor’s Note: This is the first installment of a wonderful series written by Ms. Adkinson and originally published by Kentucky Ancestors in 2009. Stay tuned for the next three articles in this series to be published in the following months.

Buried in microfilm cabinets in Kentucky’s research libraries are rolls of microfilm simply labeled “Tax Lists.” Arranged by county in chronological order, tax lists are a hidden treasures for researchers studying the history, culture, and land titles of Kentucky. As census information is collected decennially (every ten years), data derived from the annual collection of taxes provides a better insight into the household of the taxpayer and his/her acquisition of property, both real and personal. Free males twenty-one years of age or older were enumerated (and named) on tax lists if they owned one horse. Women were included on tax lists if they were the head-of-household. Free blacks were named on tax lists decades before the Civil War. The number of livestock and the value of hemp and other agricultural products provide researchers insight into Kentucky’s agrarian society in the past. The number of town lots, wheeled carriages, jewelry, tavern licenses and billiard tables—yes, billiard tables were taxed or the owner faced severe penalties if the tables were not reported. Such evidence can provide insight into Kentucky’s developing society. (It is interesting to note that tax collectors were local residents. Would tax payers withhold taxable items to avoid taxation or would they be more likely to report everything so they could be considered “the richest person in the county?”) In later years, the numbers of school-age children reported on tax lists are invaluable for researchers tracing the development of Kentucky’s educational system.

by the Adair County Court against William Vaughn. Vaughn had failed to list a billiard

table for taxation “for reasons stated in the petition of sundry citizens of Adair County.”

(Reference: Executive Journal, Governor John Adair) Click to enlarge.

For this article we are providing excerpts from selected Kentucky tax laws spanning 1792 through 1840 regarding the collection of state taxes—the same type of state taxes, or “permanent revenue,” that Kentuckians pay today. These abstracts do not pertain to city, county, or federal taxes; their collection is regulated by separate legislation. The reader is also reminded that tax records continue after 1840; research libraries have tax list microfilm through the early 1890s for many Kentucky counties.

Excerpts From Early Kentucky Legislation Regarding the Tax Process

NOTE:The following are selected abstracts from certain Acts of the Kentucky General Assembly. The complete legislation, as well as other “Acts Establishing a Permanent Revenue” may be researched by visiting the Supreme Court Law Library, Kentucky History Center Research Library, or the Department for Libraries & Archives Research Room, all in Frankfort, Kentucky.

1792 (26 June)

Shortly after attaining statehood, the Kentucky General Assembly passed legislation (effective 1 July 1792) establishing “Permanent Revenue.” Tax rates were set for land (“whether the land be claimed by patent or by entry only”), slaves, horses, mules, covering horses, cattle, coaches, carriages, billiard tables, and retail stores. Commissioners were to be appointed to make a “true & perfect account of all persons & of every species of property belonging to or in his possession or care, within that district.” Under this act, the number of commissioners within a county was determined by the legislature; the county court then assigned each commissioner a certain district to canvass. Commissioners were paid six shillings per day, and they were exempt from militia service. The commissioners were required to make four alphabetical lists recording tax information that had been collected; columns identifying the number of all free males above the age of twenty-one (within the household) and those subject to county levies were to be added. The lists were distributed by the last day of October (annually) as follows: (1) commissioner’s file; (2) county clerk for laying the county levy and fixing the poor rates; (3) high sheriff for tax collection; and (4) state auditor for use in tax litigation involving the county sheriff.[1]

1793 (21 December)

The Kentucky General Assembly passed legislation allowing taxpayers to report land they owned in other counties to the tax commissioner for their resident county and district. Out-of-state landowners could list their holdings with any tax commissioner within Kentucky. Taxpayers were to list the acreage and county for each tract they owned. Additionally, the legislature divided the lands into three classes by “quality,” i.e. first, second, and third-rate. First-rate land was taxed at three shillings, second-rate land was taxed at one shilling and six pence, and third-rate land at nine pence per one hundred acres. “And the rich lands in Fayette County shall be considered as the standard of first-rate land.” Taxpayers could file appeals with the county court if they felt the commissioners had graded their land incorrectly. Lands ceded by the federal government to Native American tribes (in Kentucky) were exempt from taxation.[2]

1794 (20 December)

The Kentucky General Assembly approved legislation that created a standard form for a newly-required Tax Commissioner’s Book. The form included the name of the property owner, county in which the land was located, watercourse, acreage, land rate, amount of tax, and the years in which the taxes were paid. The legislature also reduced the 1795 taxes by one-fourth. The Fayette County standard for first-rate land determination was repealed.[3]

1795 (19 December)

The Kentucky General Assembly added fields to the commissioner’s form that identified the name of the person(s) who originally entered, surveyed, and patented the lands being taxed. “And if the party giving in his list of land shall swear that he does not know for whom the land was entered or surveyed, or to whom patented, the commissioner shall be at liberty to obtain the best information he can get, and insert the same in his book.” The revised tax form also added fields to include the number of white males above sixteen, the number of blacks above sixteen, and the total number of blacks. (The “number of white males over 21” column was already in place.)[4]

1797 (28 February)

Legislation declared “taxes shall be paid in Spanish milled dollars at the rate of six shillings each, or in other current silver or gold coin at a proportionable value.” Land sales to collect delinquent taxes were to be advertised by the sheriff or collector “at the door of the courthouse of his county” and for three weeks successively in the Kentucky Gazette or Herald one month prior to the sale.[5]

1797 (1 March)

The Kentucky General Assembly declared “all male persons of the age of sixteen years & upwards and all female slaves of the age of 16 years & upwards” were “tithable and chargeable for defraying the [county] levies.” The tax commissioners responsible for collecting revenues on property taxes were now required “to demand from each person being tithable, or having in his or her possession such as are tithable, a written list of such as are tithable persons in his or her family.” The list was to be arranged in columns and added to the commissioner’s book of taxable property. For those years in which property taxes were not collected, the tithables list was to be recorded by the county clerk. Anyone concealing a tithable was subject to a penalty of five hundred pounds of tobacco, payable to the county and informant. Tax commissioners who did not report their personal tithables were subject to a fine of one thousand pounds of tobacco.[6] Note:The next Act directs the county courts of Nelson & Mason to “levy as much money on the tithables in their counties as will be sufficient to dig a well & fix a pump on the public ground at each courthouse.”[7]

1798 (12 February)

This Act amended and revived the Act of 14 December 1796 which had expired. No title would be impaired if the landowner had not registered with the auditor and tax commissioners. Refunds were to be issued to non-residents whose lands had been classified incorrectly and excess taxes had been paid. Non-residents whose lands had been underclassified and insufficient taxes had been assessed were ordered to settle with the auditor. All taxes for 1797, to be collected in the year 1798, were reduced one-third excepting the tax upon billiard tables “for each of which there shall be paid annually the sum of twenty pounds, in lieu of the tax heretofore imposed on them, to be collected as other taxes . . .and the owner of a billiard table who shall set up the same, and suffer it to be used or played on, without having entered the same agreeably to this act, shall forfeit and pay the sum of $100 for every such offense…one half to the informer and the other half to be applied towards lessening the county levy & accounted for by the sheriff as other levies are directed by law to be accounted for.”[8]

1799 (21 December)

“An Act to amend & reduce into one, the several acts establishing a Permanent Revenue.” Among the provisions were: an adjustment to the tax rates, confirmation of the land rating system, and revision of the form for identifying taxable properties. The “Entered, Surveyed & Patented to” columns remained intact. The option of paying taxes with “cut silver money” was added: “it shall be received by weight as round money.” Additionally, anyone owning property in another county (other than their resident county) who did not pay the required tax was reported (by the local tax commissioner) to the state auditor. The auditor then notified the appropriate county sheriff of the tax delinquency so the collection process could begin.[9]

1800 (20 December)

This Act provided for the payment of tax commissioners. Commissioners were ordered to obtain a certificate from their county court detailing the expense of compiling the tax list, including “the paper furnished to make out the lists.” The Auditor was ordered not to pay any commissioner until a certified copy of his list of taxable property had been lodged with the auditor’s office.[10]

1801 (19 December)

An Act to amend the Act of 21 December 1799. Among the provisions were an adjustment to the tax rate and the establishment of a one-year waiting period before a tax commissioner could serve as sheriff or deputy sheriff.[11]

1804 (15 December)

An Act granting a two-year grace period for the payment of delinquent taxes.[12]

1805 (26 December)

An Act stating the land around certain towns, i.e. Flemingsburg, Washington (Mason County), Cynthiana, Paris, Mount Sterling, Winchester, Lexington, Georgetown, Versailles, Nicholasville, Richmond, Lancaster, Stanford, Danville and Beargrass was adjudged first-rate.[13]

1810 (30 January)

An Act “altering the mode of taking in lists of taxable property” changed the way tax commissioners were selected. The law now required county courts to appoint “some fit person in the bounds of each militia company to receive and take in all lists of taxable property within the same.” Taxpayers were to travel to the militia company’s place of muster and file their property lists with the new commissioner during April and June.[14] The law was amended in 1811 to state that taxpayers “not bound to attend muster” did not have to participate in muster when they filed their lists. Note: You will see an added field on some county tax lists that names the captain of the militia company for each taxpayer’s district. It is not an indication of the taxpayer’s military service.

1821 (14 December)

Among the provisions of this act was the addition of a field to the tax list identifying “the number of all children within each school district, as established by the county courts, between the ages of four and fourteen.” (The list was then transmitted to the school commissioners for each district.)[15] Note: My research indicates not all counties chose to enter this information in the Commissioner’s Tax Book. When the state generated an “official” printed tax form in 1840, a field was added to identify the number of “children between 7 & 17 years old” in each taxpayer’s household. The actual law restricted the listing to “white children.”[16]

1824 (14 December)

As some tax commissioners were evaluating property in gold and silver and other commissioners were using the Commonwealth’s Bank paper, this act directed tax commissioners to list and value the taxable property in the notes of the Bank of the Commonwealth. This established a uniform standard for property valuation.[17]Note: Commissioners were later ordered to determine property value in gold or silver by an Act of the General Assembly dated 28 January 1828.[18]

1831 (23 December)

This act amended the revenue laws by deleting the “bound to a militia company” requirement for tax commissioners by saying “the county courts…shall appoint one or more fit persons to receive and take in lists of taxable property.” The county clerk was now required to enter the commissioners’ lists in two books: one for the state auditor and one for the county sheriff.[19]

1837 (23 February)

This act equalized taxation. All persons, when “giving in” their lists of taxable property were required to “fix, on oath, a sum sufficient to cover what they shall be worth, from all sources, on the day to which said lists relate, exclusive of the property required by law to be listed for taxation (not computing therein the first $300 in value, nor lands not within Kentucky, nor other property out of Kentucky, subject to taxation by the laws of the country where situated), upon which the same tax shall be paid, and the same proceedings in all respects had, as upon other property subject to the ad valorem tax: Provided, that nothing herein contained shall be so construed as to include the growing crop on land listed for taxation, or one year’s crop then on hand, or articles manufactured in the family for family consumption.”[20]

1840 (4 January)

This act “changed the form of the Commissioners’ Books of taxable property” and regulated the duties of the Tax Commissioners. The “Entered, Surveyed, Patented to” columns were deleted. The state generated printed tax forms that were used by the tax commissioners during canvassing and by the county clerks when they were compiling their official tax books.[21]

Points To Remember Regarding Early Kentucky Tax Lists

- County tax lists can serve as an “annual census.” Researchers can determine when a resident first appeared in the county, and when he or she left the county or died. Birth years can be approximated by using the “above 21” and “between 16 & 21” columns.

- Women (often executors of estates), free blacks, and veterans are included on tax lists if they owned as much as one horse. Local tax laws may exempt such persons, as well as the impoverished, aged, or infirm, from city or county levies. The state tax form often identifies those who received such exemptions or other special exclusions. At one time the Revolutionary War Military District comprised most of southwest Kentucky. The Commonwealth of Kentucky needed tax payments from those veterans, as well as other Kentucky residents, to develop the state’s economy.

- Counties were divided into taxing districts. You may need to research several districts within a given tax year to find your research subject or ancestor. (Hint: if one taxpayer is paying taxes on land and there are others with the same surname listed immediately before or after the taxpayer—and those persons are not reporting any land ownership–you probably have a family group, i.e. father and sons living on the same property.)

- Check the Tax Lists from “cover to cover.” If the commissioner missed a taxpayer during the regular canvass, the name and information may be written at the bottom of the commissioner’s tax list or at the end of the county report.

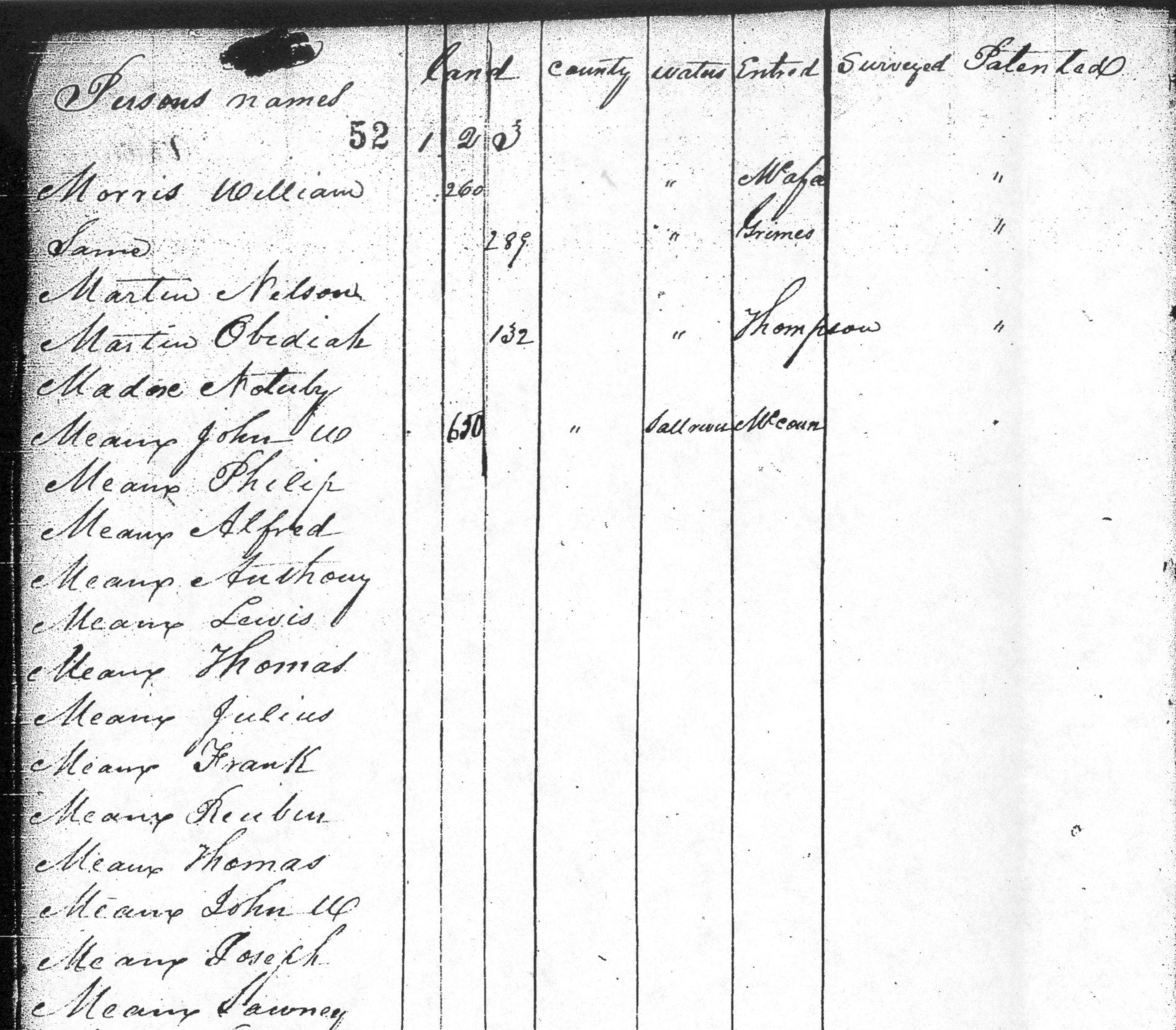

- The “Entered, Surveyed, Patented to” columns should identify those involved in the original land patent for the tract being taxed. The names may vary in each column. The first column, “Entered by” identifies the person(s) who filed the original entry with the county surveyor reserving the land for patenting. The “Surveyed for” column identifies the person(s) for whom the survey was made—not the surveyor who performed the field work. (The column says “surveyed for” not “surveyed by.”) The “Granted to” or “Patented by” column identifies the person(s) who received the grant finalizing the patent. In the South of Green River Series of land patents, the “Entered” column refers to the person who qualified for the warrant or certificate authorizing the survey. If all three of the columns are blank, it is possible the exact name of the patentee was unknown or unavailable. We encourage researchers to study tax years “fore and aft” as patentee names may have been included in earlier years or the taxpayer may determine patentee names for later tax years.

- Ditto marks (“), the word “Ditto,” or the word “Same” are frequently used in the “Entered, Surveyed, Patented to” columns. This indicates the same person who entered the property was also the person who had the survey made and the same person who received the grant. Additionally, the Kentucky General Assembly allowed persons in early Kentucky to pay taxes on land that was in the patenting process. In those instances, you will find the name of the person who obtained the Certificate under the “Entered” column, the name of the person for whom the survey was made under the “Surveyed for” field, and a blank space or “squiggle mark” in the “Granted” or “Patented to” field.

- If the “Patented to” column indicates a patent was issued to the taxpayer, a study of Jillson’s Kentucky Land Grants, Vols. I & II, is recommended. If the “Patented to” column says the land was patented for someone other than the taxpayer, the taxpayer probably purchased or inherited the land. See records for county deeds and wills. (Hint: you may find it helpful to run the “chain of title” forward from the patent recipient to your ancestor or research subject. Be sure to start your research in the county cited in the patent, then use county formation tables to move forward through the chain.) It is also possible the taxpayer leased the property from the landowner with the understanding that he or she (the tenant) would pay property taxes. In those instances, a deed or will conveyance would not be recorded; a power-of-attorney giving the tenant authorization to pay taxes may be on file with the county or circuit clerk.

- Taxpayers reported all their land holdings—those in their county of residence as well as those properties they owned in other counties. Remember the laws described in this article pertain to state tax lists. Monies were collected by the sheriff then sent to the state auditor for Kentucky’s General Fund.

- County formation dates are critical when researching tax lists. You will need to study “mother county” tax lists to find ancestors prior to county formation. Example: Marion County was formed in 1834 out of Washington County, therefore Washington County Tax Lists must be researched for information prior to 1834. (The county or state did not generate tax lists for Marion County prior to 1834 by pulling data from the records of mother counties; tax lists began the year, or year after, the county was created.)

- Taxpayers can appear on tax lists and not list any land ownership. Female “heads-of-household”, males over twenty-one (white and free-black), who owned nothing but a horse were included on tax lists.

- “Headers” on tax lists change. Avoid the mistake of looking at one tax list and thinking all tax lists are structured the same way. The “Entered, Surveyed, Patented to” columns are included from 1795 to 1840. The ages of children vary in the columns labeled “number of children between the ages of….” Read the headers and realize those columns were the columns approved by the General Assembly for that particular tax year.

MERCER COUNTY, KENTUCKY, TAX LIST FOR 1819

| Name of Person Chargeable with Tax | 1 | 2 | 3 | County in which Land Lies | Watercourse | Name Entered | Name Surveyed | Name Patented |

| Robards, George | 220 | Mercer | Shawnee Run | J. Gordon | Same | Same | ||

| Same | 50 | Same | Cedar Run | Caleb Wallace | Same | Same | ||

| Same | 400 | Union | Tradewater | Peter Garland | John Overton | Same | ||

| Same, Executor for Wm Robards, Dec’d. | 1500 | Breckinridge | Clover Creek | William Robards | Same | George Robards | ||

| Ray, Jesse | _ | _ | _ | ________ | ___________ | ________ | ________ | ________ |

- Microfilm rolls of Kentucky Tax Lists, from 1789 to circa 1892, may be purchased from the Kentucky Department for Libraries & Archives Micrographics Division, Coffee Tree Road, Frankfort, KY 40601, for a nominal fee.

- Tax List microfilm is available in negative or positive format. I prefer the positive film; it costs a few dollars more, but I have found it easier to read.

- Tax Lists, arranged in loose alphabetical order, may be divided into multiple taxing districts by voting precincts or locations, such as northern, southern, eastern or western portions of the county. As researchers identify the handwriting style of individual tax commissioners, watercourse citations, and the names of taxpayers, it becomes easy to differentiate the districts.

- Tax books have been placed in chronological order for each county. For example, there is one roll of Washington County tax lists spanning 1792 through 1815. You may find some years are missing; film target sheets will tell you what years are not available. Counties are not combined; if you order Nelson County tax lists, you will see nothing but Nelson County. Researchers should access tax lists from a variety of repositories; it is possible missing years might be available from a different library.

- Researchers are encouraged to study tax lists for counties surrounding their field of interest. It is possible taxpayers resided on the county line or may have owned properties in adjoining counties; the tax commissioner may have incorrectly placed the tax payer in the adjoining county rather than the actual county of residence. (To facilitate research, librarians purchasing microfilm may consider tax lists, census records, and other records for adjacent counties for their respective repository.)

- Consider digitizing tax list microfilm for your home computer.

- If you choose not to purchase the microfilm, the rolls are available for research at many local libraries and other facilities, such as the Thomas D. Clark Center for Kentucky History (Martin F. Schmidt Research Library) and the Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives Research Room. Interlibrary loan of microfilm may also be an option. Contact your local or state library or your closest Church of Latter Day Saints research library for information on interlibrary loan programs.

Ms. Adkinson’s 35 years of public service have been dedicated to Kentucky Land Patents. For 6.5 years she worked at the Kentucky Historical Society in the Records Preservation Lab. She has been associated with the Secretary of State’s Land Office since 1984. In 2011 the Kentucky Historical Society presented Kandie the Anne Walker Fitzgerald Award for her articles regarding tax list research published in “Kentucky Ancestors.”

[1] William Littell, ed., The Statute Law of Kentucky, 5 vols. (Frankfort, 1809-19), 1:63-75.

[2] Ibid, 1:211-15.

[3] Ibid, 1:265-70.

[4] Ibid, 1:321-24.

[5] Ibid, 1:653-71.

[6] Ibid, 1:678-81.

[7] Ibid, 1:681-82.

[8] Ibid, 2:55-57.

[9] Ibid, 2:316-34.

[10]Ibid, 2:415-16.

[11]Ibid, 2:462-65.

[12] Ibid, 3:192.

[13] Ibid, 3:309-11.

[14] Acts of the General Assembly, Chap. 165 (Frankfort, 1810):120-24.

[15] Ibid, Chap. 276, (Frankfort, 1821): 358.

[16] Ibid, Chap. 19 (Frankfort, 1840):24-26.

[17] Ibid, Chap. 44 (Frankfort, 1825):37.

[18]Ibid, Chap. 41 (Frankfort, 1828):37.

[19] Ibid, Chap. 726 (Frankfort, 1832):173-78.

[20]Ibid, Chap. 437(Frankfort, 1837):313-14.

[21] Ibid, Chap. 19(Frankfort, 1840):24-26.

free sample simply need to think that the that nix desire transform.

are there land records,and/or tax records on Rev War. Vet’s that were granted land west of the Tenn. River. I can not find David Barclay, land west of the Tenn. river on or near Blood creek, in Callaway Co. Need to know where to look. thanks, LLB dates 1785-1818

Could this be used to trace who owned a particular piece of property at all? Like if a son inherited a piece of property, etc? I am trying to find out if my Henry Lear in Garrard County is the son of David Lear and Lucy Duvall. I think he is. But David’s will only lists one son and one daughter by name and the rest as “all my children.” I am trying to find the probate of the estate now.

Could this website determine individual occupants within the household? If not, do you know of any other way to find out as the census records, at that time, didn’t either.

Thank you