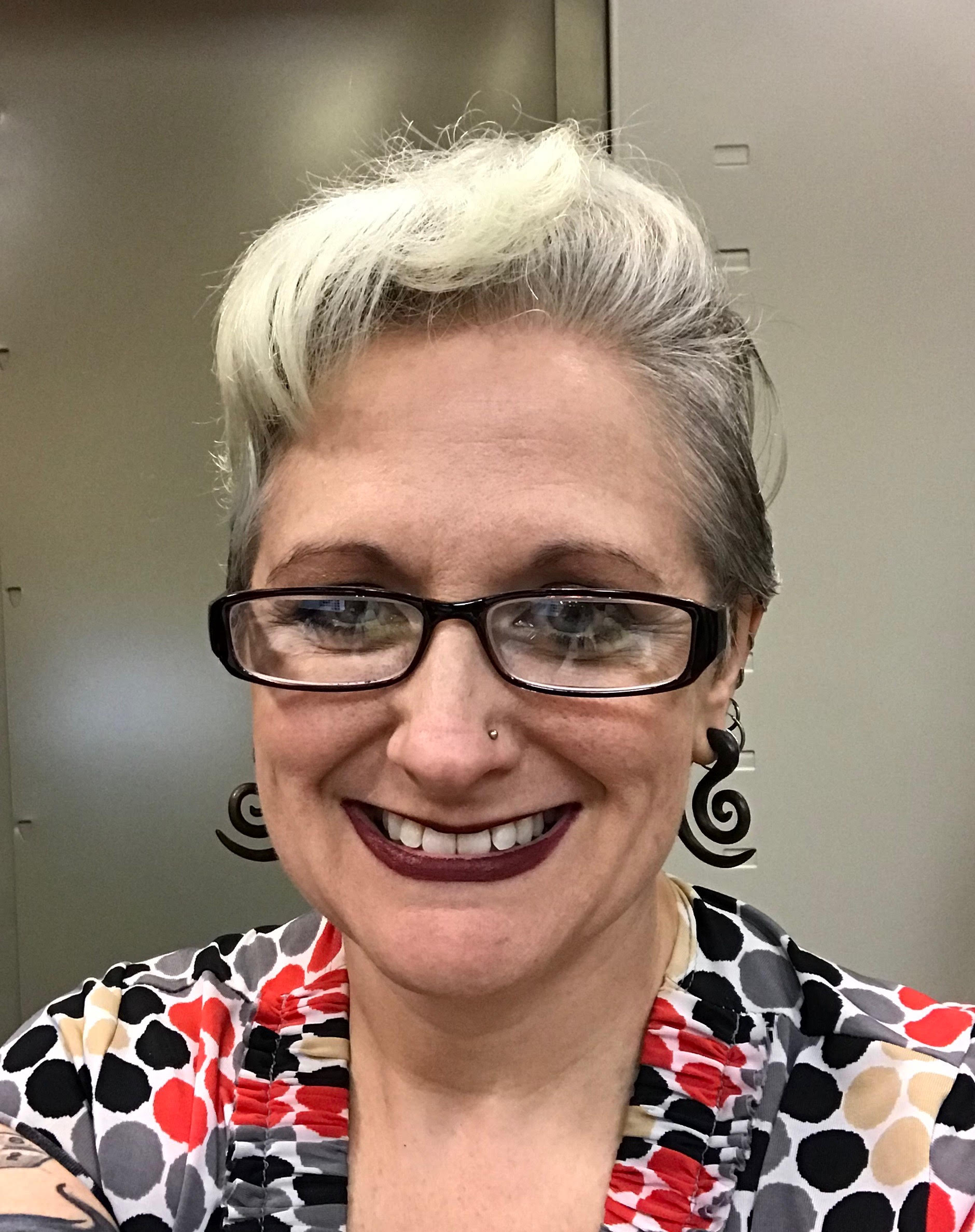

By: Jama Watts, MLIS, Reference & Genealogy Librarian, Marion County Public Library

They say that in real estate, the key is “location, location, location.” In genealogy, the key is “document, document, document!” Even if you’re not planning on publishing a book about your family history or applying to a society like the DAR or SAR, documentation is still an important part of any genealogy research. You wouldn’t have considered trying to turn in a research paper without citing your sources, would you? Not and expect to get a passing grade! Think of your genealogy research as the foundation of a really intense research paper that centers around you and your family. The outcome is just way more personal than any other research paper you’ve ever written.

They say that in real estate, the key is “location, location, location.” In genealogy, the key is “document, document, document!” Even if you’re not planning on publishing a book about your family history or applying to a society like the DAR or SAR, documentation is still an important part of any genealogy research. You wouldn’t have considered trying to turn in a research paper without citing your sources, would you? Not and expect to get a passing grade! Think of your genealogy research as the foundation of a really intense research paper that centers around you and your family. The outcome is just way more personal than any other research paper you’ve ever written.

Still need convincing? Let’s look at it another way – Documenting your sources will save you time and energy! How?

- Documenting your research helps you know which sources you’ve already perused and what you found there. Ever find yourself thumbing through a book only to realize that you’ve already checked it? Documenting which sources you’ve already checked will keep you from wasting time on duplicate searches.

- Keeping track of a full list of sources you’ve checked and what you were looking for will aid in reminding you that you only checked a source for one thing & not another, i.e. you checked for “Raleys” but not “Spaldings”.

- Documenting your research helps give your confidence if someone else’s research contradicts your own. How many times have we gotten a hint from someone else’s family tree on Ancestry and started second-guessing ourselves? Attaching supporting documentation will keep you from referencing someone else’s incorrect research.

- Keeping a list of people with whom you’ve corresponded, as well as their contact information will help you in a pinch. This is really helpful in case you need to verify other information or need further clarification. Perhaps you contacted several libraries about obituaries and want to see if there are obits for the spouses. Keeping that contact information and what was sent will help you narrow down your requests. Many times, there are stipends for that research. If you know which librarian sent you that information, that’s less requests (and payments) that you’re sending out.

If you haven’t documented your findings in the past, it’s quite an easy habit to get into. I admit, before I started working as the Genealogy and Reference Librarian at Marion County Public Library, I tended to take my family’s word on their family history data. Working in a professional environment, I needed to make sure that my patrons knew where the information was located. This translated over to my personal research and my family tree has reaped the rewards.

Things you’ll want to keep track of include:

Author of the work, even if it’s just a pedigree chart on Ancestry. For someone’s story, etc. on Ancestry, make sure you write down the exact URL of the information, just in case you need to come back to it. Don’t just assume you’ll remember what you meant if you quickly jot down “Watts family tree on Ancestry.”

Author of the work, even if it’s just a pedigree chart on Ancestry. For someone’s story, etc. on Ancestry, make sure you write down the exact URL of the information, just in case you need to come back to it. Don’t just assume you’ll remember what you meant if you quickly jot down “Watts family tree on Ancestry.” - Title of the published work or a well-written description (i.e. “George family folder at Marion County Public Library, Lebanon, Kentucky”).

- Publication information (publisher, location, year, edition).

- Date you accessed the information. This is especially helpful for internet searches, as information can be updated or changed over time.

- Location of the source (i.e. Sons of the American Revolution Library, Ancestry.com, Kentucky Historical Society)

- Specific reference (chapter, page #, etc.)

If you’re printing information or making copies, remember to write the information on the back of the page. I do this for every page I print out from our microfilm machine and every copy I make out of a book or family file, i.e. the title of newspaper, date, perhaps the page on which it appeared. It also helps to keep a separate log of all of the items you searched at each location. This sounds like a lot of work, but think about how much time you’ll be saving yourself in the future. Just in case you don’t believe me, here are some of my real life examples:

I was working on my own family tree, focusing on my mother’s side. One of her lines is the Lauderdale family. I got back to John Lauderdale, born 1744 in Virginia, but could not get back any further. Using Ancestry’s hints, I was directed to a few stories on a gentleman named John of Nolichucky Lauderdale. The story cited a work by Clint Lauderdale (“History of the Lauderdales in America, 1714-1850”), stating that the Lauderdales were originally Maitlands from Scotland, but changed their name based on the Earl “to whom they were related or for whom they were tenant farmers.” While this information isn’t completely correct, it did give me the correct direction in which to look. From here, I found an entire thread on Ancestry about the Maitlands/Lauderdales, which then directed me to the Clan Maitland website. Without this researcher’s documentation, I would have been left scratching my head at another brick wall.

I was working on my own family tree, focusing on my mother’s side. One of her lines is the Lauderdale family. I got back to John Lauderdale, born 1744 in Virginia, but could not get back any further. Using Ancestry’s hints, I was directed to a few stories on a gentleman named John of Nolichucky Lauderdale. The story cited a work by Clint Lauderdale (“History of the Lauderdales in America, 1714-1850”), stating that the Lauderdales were originally Maitlands from Scotland, but changed their name based on the Earl “to whom they were related or for whom they were tenant farmers.” While this information isn’t completely correct, it did give me the correct direction in which to look. From here, I found an entire thread on Ancestry about the Maitlands/Lauderdales, which then directed me to the Clan Maitland website. Without this researcher’s documentation, I would have been left scratching my head at another brick wall.- Another example comes from work that I was doing for a researcher. In looking for confirmation of the names of their great-great-grandparents, I came across a family pedigree chart in one of our family files. This chart cited a family bible, but we did not have access to the bible itself. However, the individual’s name who did the research was on the paperwork. I put the two researchers in touch with each other and was told that the originator of the pedigree chart actually owned the bible, allowing the lineage to be confirmed.

The Genealogical Proof Standard Can Help:

Perhaps the best reason to document your research is the possibility of publishing your research in the future. Even if you don’t think you’ll publish, you might change your mind in the future. You’ve done all of the work, why not share it with others? If you do decide to publish, many researchers will be looking for the Genealogical Proof Standard (GPS). The Standard itself consists of five points:

- A reasonably exhaustive search for all pertinent information.

- A complete and accurate citation to the source of each item used.

- Analysis of the collected information’s quality as evidence.

- Resolution of any conflicting or contradictory evidence.

- Arrival at soundly reasoned, coherently written conclusion.

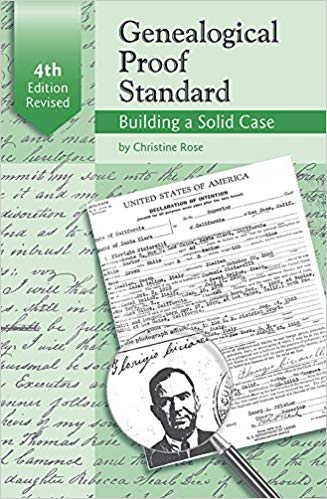

The Standard sounds more daunting than it actually is. Think of the Standard in the meaning of another device that shares its abbreviation – GPS. It helps show you where you’re going and where you’ve been! Check out Christine Rose’s book “Genealogical Proof Standard: Building a Solid Case” for more information on the standard and how to utilize it.

The Standard sounds more daunting than it actually is. Think of the Standard in the meaning of another device that shares its abbreviation – GPS. It helps show you where you’re going and where you’ve been! Check out Christine Rose’s book “Genealogical Proof Standard: Building a Solid Case” for more information on the standard and how to utilize it.

Maybe you’re already citing your sources. Maybe you just needed a reminder as to why it’s important. Or maybe you don’t think you need documentation because “no one else in the family cares about our past.” Even if no one else does now, someone will down the line or perhaps someone from a different branch. And more importantly, it’s important to you. So make your time and research count.

Jama Watts, MLIS, is the Reference and Genealogy Librarian at the Marion County Public Library. She holds a Bachelors in Art with an emphasis in Art History from Campbellsville University and a Masters in Library and Information Science from the University of Kentucky. Jama is also serving as Chair of the Genealogy and Local History Round Table for the Kentucky Library Association.

References

“Calling All Maitlands, and Mautalents, Mautalens, Lauderdales, Maitlens, Medlins, Maizlands.” Clan Maitland. September 26, 2017. Accessed August 16, 2018. http://www.clanmaitland.org.uk/.

Helennred. ” Lauderdale History (Maitland Family).” Ancestry. Accessed August 16, 2018. https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/collection/1030/tree/106174391/person/170058506420/media/1f719b42-90f7-4375-9b83-35a6552a5b21?_phsrc=Htu300&usePUBJs=true.

Personal story added to an Ancestry family tree.

Meyerink, Kory L., MLS, AG. “Why Bother? The Value of Documentation in Family History Research.” Genealogy.com. Accessed August 16, 2018. http://www.genealogy.com/articles/research/19_kory.html.

Powell, Kimberly. “Researching Your Family Tree? How to Establish Proven Connections.” ThoughtCo. March 17, 2017. Accessed August 16, 2018. https://www.thoughtco.com/genealogical-evidence-or-proof-1420515.

Rose, Christine. Genealogical Proof Standard: Building a Solid Case. San Jose, CA: CR Publications, 2014.

Stahle, Tyler S. “Understanding the Genealogical Proof Standard.” FamilySearch. April 05, 2017. Accessed August 16, 2018. https://www.familysearch.org/blog/en/genealogicalproofstand

I am researching my Carpenter Family History and their Kentucky Ancestry and have hit a brick wall. I am looking for a professional geneaologist and appreciate any assistance you may be able to provide.

My father was John Elmer Carpenter, born 1920 in Danville, Kentucky, Grandfather was Elmer Carpenter, born 188(6?) and Great Grandfather Wilson Carpenter born in Rockcastle or Breathitt County Kentucky about 1830. Beyond that I am lost and need help. All Carpenter family members seem to be born in that area.

Asking for library assistance or referral to professional genealogist to build Carpenter Family Tree. I have hit a wall with great-grandfather Wilson Carpenter DOB: 1861 in Rockcastle County, Kentucky. Married to Georgia Anne Owens in 1877. DOD July 11, 1950 in Danville, Kentucky. His son, my grandfather, Elmer Carpenter Born 31 Dec 1887 in Mt. Vernon, Rockcastle, Kentucky. Killed in railroad accident on 19 Dec 1925 Danville, Kentucky, Boyle County. Please let me know if you can provide genealogy assistance or library records. Thank you! Linda Carpenter