By: Cheri Daniels, KAO Editor/KHS Head of Reference Services & Deana Thomas, KHS Archivist

In 1995, the Carpenter Family Papers were donated to the Kentucky Historical Society (KHS). The scope of the collection runs from 1788 to 1928, and includes documents from several members of this family as well as their acquaintances. While the overall description is justified in these parameters, recent collection focus has shifted to the life of Catherine Carpenter (1760-1848). In 1806, this mother of 12 children was widowed for the second time, and left to run the large family farm in Casey County, which she did quite successfully. In fact, she was very hands-on and dedicated to making this endeavor succeed as a legacy for her family.

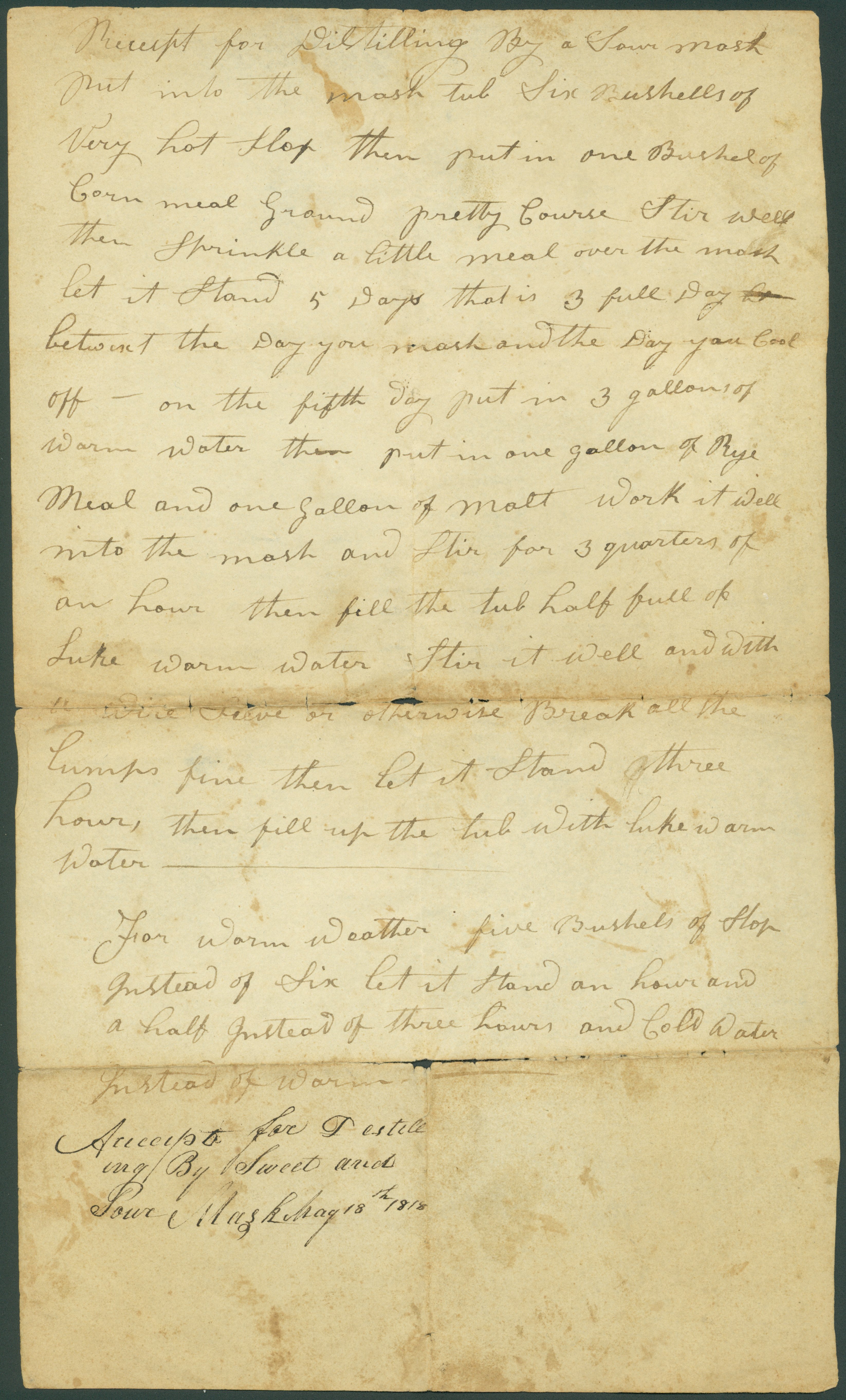

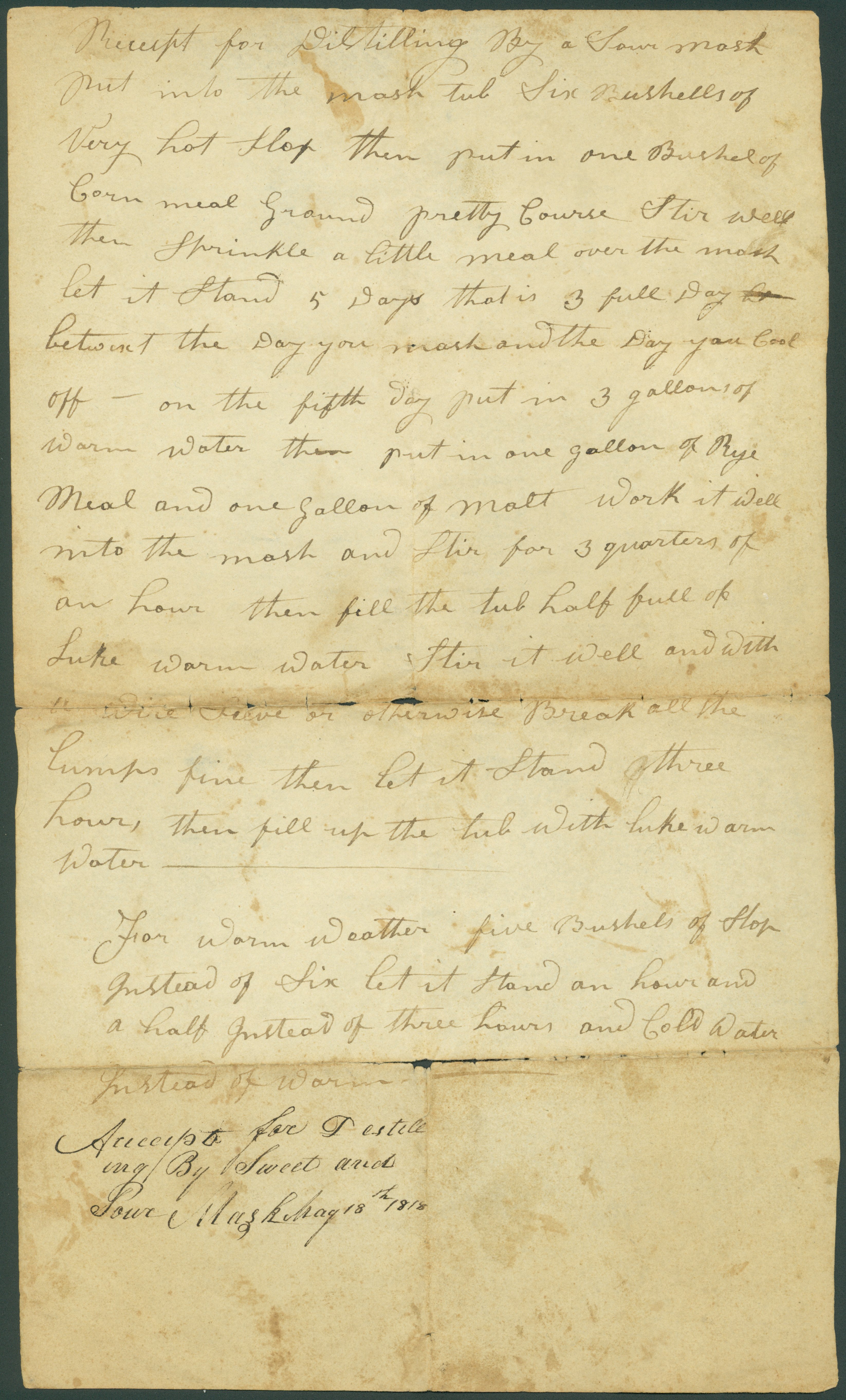

Within the documents from Catherine’s life span was found a hand-written double recipe for distilling spirits. One side of the document includes a recipe for sour mash whiskey, and on the other side, a recipe for sweet mash whiskey. The document also includes a secondary note at the bottom, written in different colored ink, attributing the recipe to 1818.[i] There is no mention of authorship.

Despite a lack of attribution, a narrative has developed, claiming these to be Catherine Carpenter’s mash recipes. Did Catherine create these recipes, use these recipes, or were they shared recipes among the family/community?

Catherine and the Carpenter Family:

Catherine Spears was born in Virginia about 1760 to German immigrants, George and Christina (Hardwin) Spears.[ii] Sometime prior to 1780, Catherine married fellow Virginian, John Frye. In 1780, the couple, with their young daughter, Leah, joined Catherine’s sister, Elisabeth Spears Carpenter and her husband John Carpenter, as John and his brothers, Adam and Conrad Carpenter, traveled west into the new Kentucky territory.

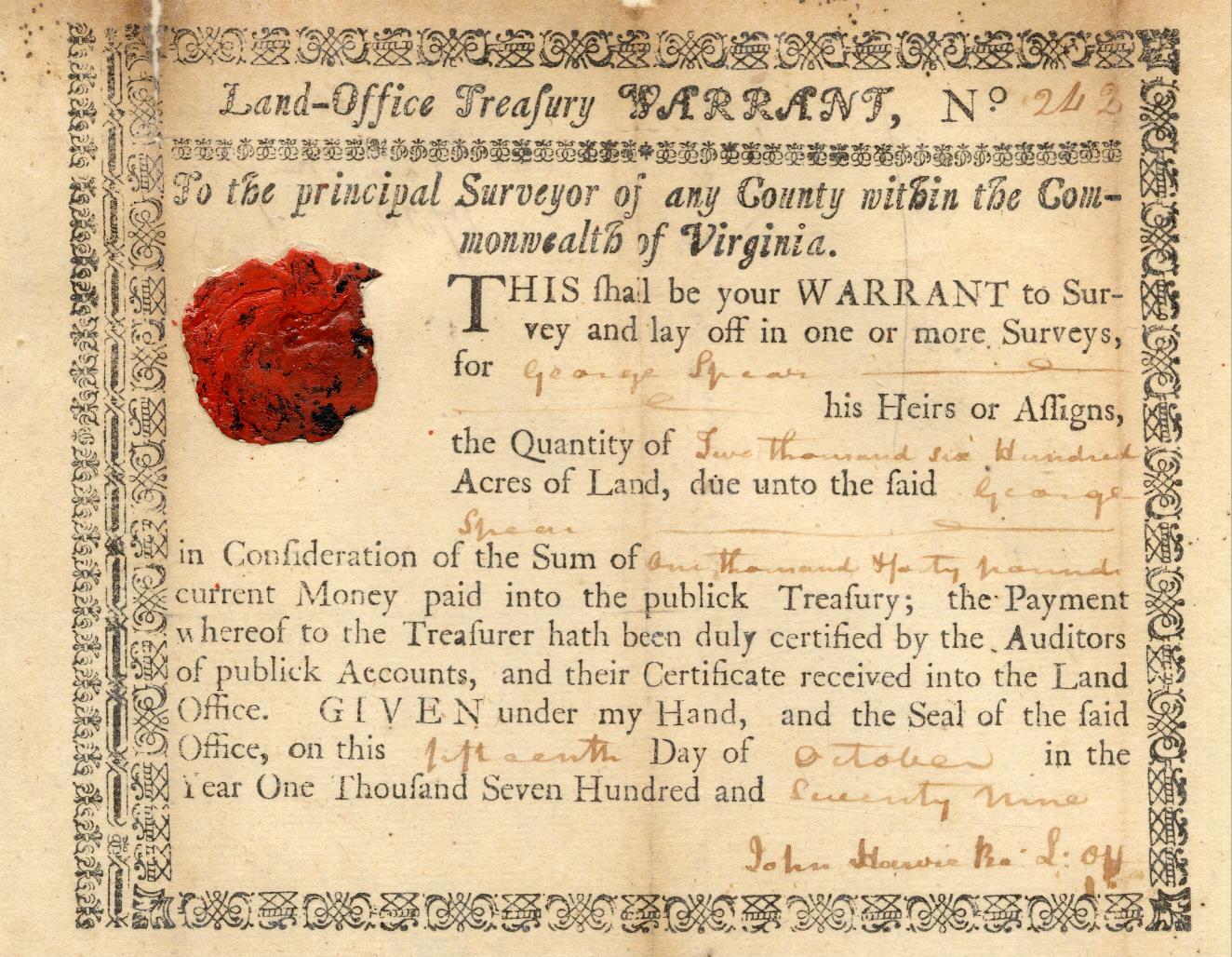

The group settled in the newly formed Lincoln County, Kentucky at a place they named Carpenter’s Station. The land included in Carpenter’s Station (near present day Hustonville, along “Carpenter’s Creek”) was a result of the Carpenter, Spears, and Frye family efforts to purchase large chunks of land under the Virginia Treasury Warrant system. The earliest Treasury Warrants were bought by George Spears and George Carpenter in 1779.[iii]

As the Revolutionary War progressed, the father, George Carpenter, and a couple of his sons provided some military service, resulting in George’s death prior to the family’s migration. Due to the service of George and his son John, both men received military warrants to settle land – but this was for a western portion of the state that was outside of their general treasury warrant settlement parcels. The remaining Carpenter men fulfilled the settlement requirement based on the treasury warrants in hand. With the deaths of their father George, and brother, John Carpenter, the surviving Carpenter men also built their land holdings through inheritance. The area settled by this group would later be split via county divisions to form parts of Lincoln and Casey Counties in 1807.

Catherine’s husband, John Frye was killed at the Battle of Blue Licks in 1782 leaving Catherine a pregnant widow at 22 to care for this new baby and their young daughter, Leah. After the birth of her second child, John Frye Jr., Catherine married Adam Carpenter in 1784 and the new couple settled in an area along nearby Frye Creek, with both Adam’s collection of land parcels, and the large acreage that was being held in trust for the heirs of John Frye.

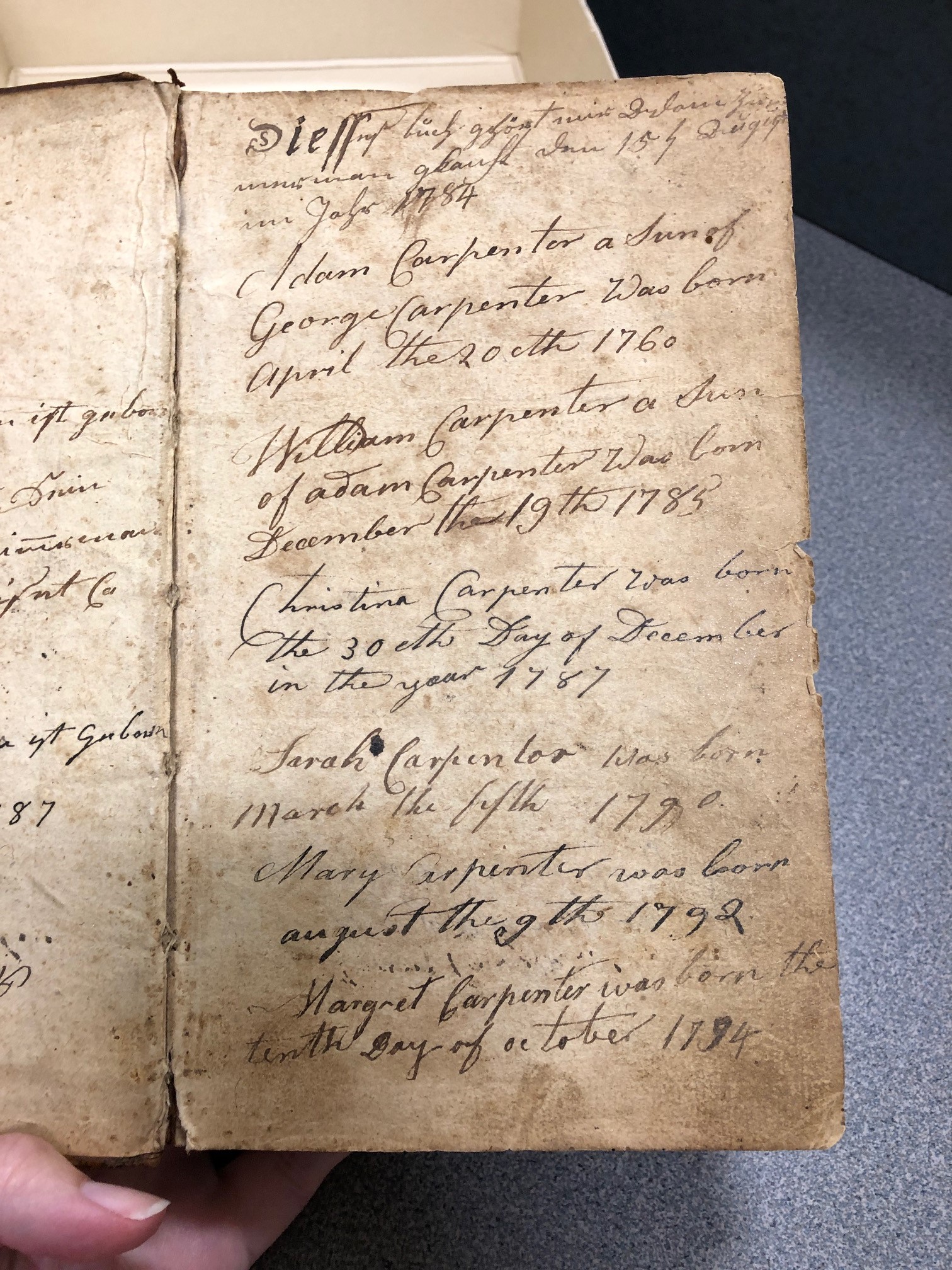

Over the next 22 years, Catherine gave birth to 10 more children: William, Catherine, Christina, Sarah, Margaret, George, Conrad, Henry, Adam and Mary.

The life Adam and Catherine built together was one very much like that of their neighbors and other family members. After putting together a few parcels of land in the area which was comprised of almost 1000 acres, they raised children, produced various crops, tended livestock, rented out land parcels, and converted surplus corn into distilled spirits. This practice of distillation was very common among the early settlers:

“The distillation of liquor or brandy occupied the same place in their lives as did the making of soap, the grinding of grain in a rude hand mill, or the tanning of animal pelts; distilling equipment was as necessary as the grain cradle, the hand loom, or the candle mold.”

Kentucky Bourbon: The Early Years of Whiskeymaking by Henry G. Crowgey (1971, p.25)

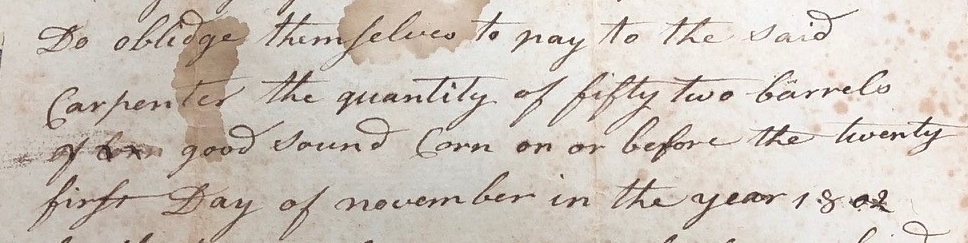

In 1792, one of the renters of Carpenter (or Frye) land paid his rent to Adam Carpenter in the form of 50 barrels of corn – hinting at an alternative purpose for this commodity.

According to subsequent records, Adam Carpenter died in 1806 at the age of 46. In Adam Carpenter’s settlement records, one third of his estate was given to his wife Catherine and the remaining two thirds were to be split amongst his 10 children. Adam named George Murrell and George Carpenter executors of his estate, with William Crow of Lincoln County being later named guardian of the Carpenter children.

Catherine as Head of Household:

From Adam’s estate, Catherine inherited 667 acres, several farm animals (hogs, sheep, lambs, horses, pigs, and cows) as well as a number of household furniture and equipment. Perhaps the most significant “item” left to Catherine, was “one negro boy”.[iv] This is the first mention of slaves associated with the Carpenter household.

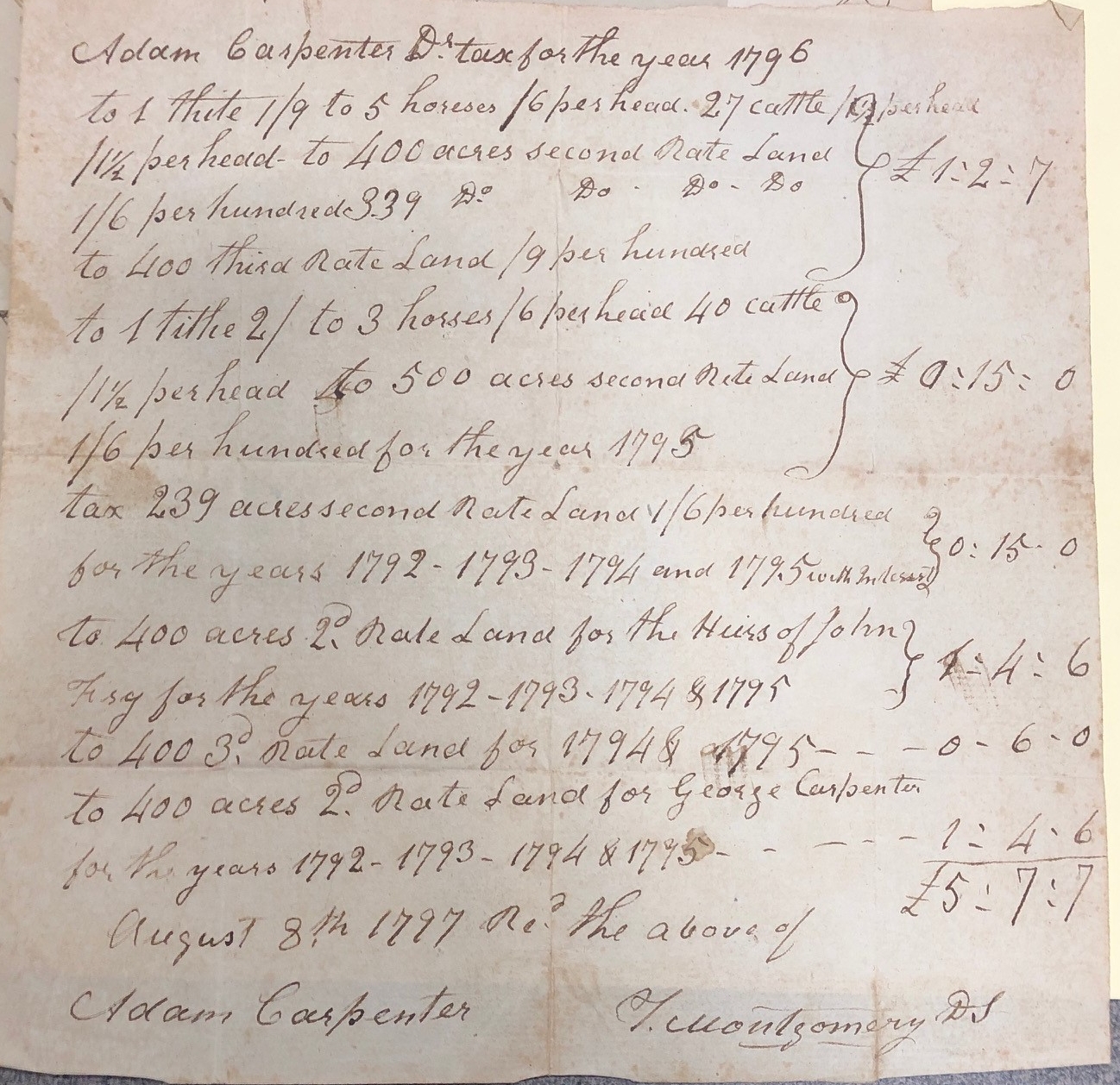

As a widow, Catherine kept the farm going successfully until her death in 1848 – but with a lot of help. Upon the death of her husband, there are several land exchanges, tax payments, and slave purchases over the years, all in the name of Catherine. By 1815, Catherine is recorded as paying taxes on 100 gallons of distilled spirits.[v] This indicates that Catherine was secure in acting as the head of household, not only as an heir of Adam Carpenter, but as an heir of her father’s Virginia estate which yielded a regular income after the executor chose to purchase the Rockingham County land and pay the heirs regular installments over several years.[vi]

With the passage of time after Adam’s death Catherine bought additional land, including 100+ acres in Green and Adair counties. Moreover, according to the receipts found in the collection, as well as census records, Catherine purchased a number of slaves in the subsequent decades. Her enslaved population averaged in the neighborhood of 13-15, mostly young, males and females within the age range of 12-25 – with the exception of one older male, whom we assume is the enslaved man “Joseph” who was given his freedom and a place to live after Catherine’s death.[vii]

With the increase in land holdings, the purchase of additional slaves, and the amount of taxes she paid between 1806 and 1848 it appears that Catherine remained a large and wealthy landowner, focusing on weaving, raising crops, and distilling spirits from excess corn. In fact, in the 1845 Casey County tax list Catherine was worth over an estimated $13,000.[viii]

The Obstacle of Literacy:

With all of the documentary evidence indicating that Catherine was a successful woman of business, there is one problem that sheds a light of doubt on the authorship of the sour/sweet mash whiskey recipes. Catherine Carpenter could not read or write.

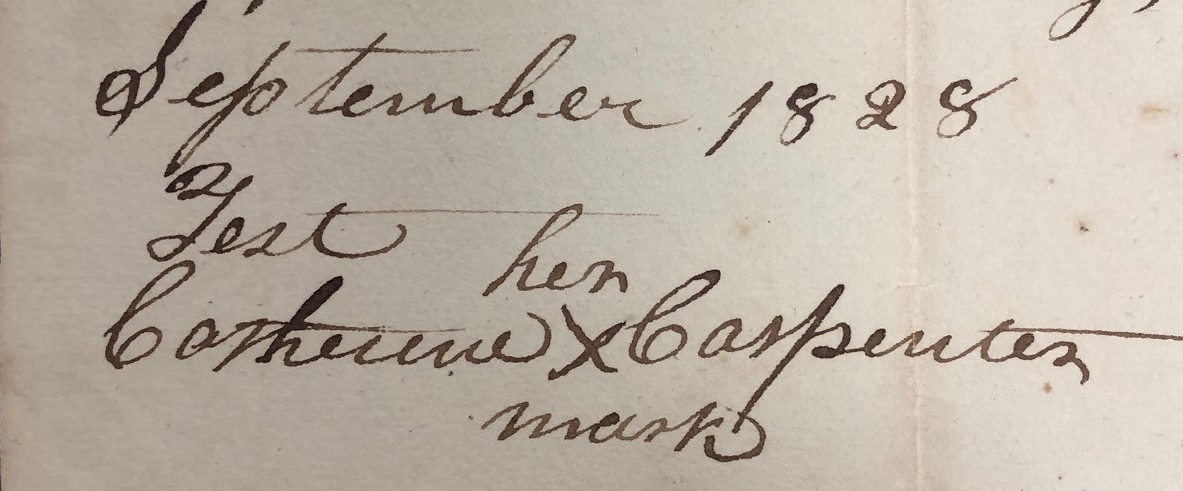

The evidence we have for Catherine’s illiterate state lies in a few of the documents in the Carpenter Family Collection. For several of the legal transactions, and even for her own will, Catherine’s name appears at the end of the documents with her mark of “X” given in the place of a signature. This indicates that she could not write her name.

For further evidence, the 1840 Federal Census lists Catherine as the only free white person in the household, with an accompanying hashmark in the column: “Could not read or write.”

Over many decades, Catherine Carpenter collected several different written aids for running her farm. Included in the collection, from prior to her husband’s death, and after, are examples of food recipes, household chore recipes, weaving patterns, and these sour/sweet mash recipes of 1818. Many of the household recipes and weaving patterns have names of authorship from outside sources, including various members of the Carpenter family. When looking at the documents that comprise this collection, it is clear that the sour/sweet mash recipe has a very similar hand writing style to that of many other legal documents put together on behalf of Catherine. This is not a surprise, as Catherine solicited attorneys on her behalf, and had several children of an age that could have helped in this area, including her son, George Carpenter, who was said to have helped a great deal in the running of the farm.

Conclusion:

Did Catherine Carpenter personally write these sour/sweet mash whiskey recipes? Due to her illiterate state, no, we cannot say that she wrote them. Did she construct these recipes? That is a feasible summation, but let’s consider her community in 1818.

Several of the other recipes in her collection came from male members of the nearby Carpenter family. The guardian of Catherine’s children, William Crow, had a license to distill whiskey in nearby Lincoln County in 1814, four years before the recipes were put down onto paper.

However, despite the potential alternative authors or creators of these recipes, it is our conclusion that Catherine more than likely used these recipes to instruct her household members, including the 19+ enslaved workers, who had a significant hand in making the farm a financial success, how to distill a proper batch of sour or sweet mash whiskey – from 1818-1848.

PostScript: Carpenter Genealogy and Naming the Enslaved:

This collection is full of genealogy gems for many families, both free and enslaved.

The earliest piece of genealogy we have for the Carpenter family is the 1773 German family Bible brought over with them when immigrating to the Colonies in the 18th century. One mystery the Bible solves is the change of surname from Zimmerman to Carpenter – the literal translation of the surname Zimmerman. Some confusion arose later in our research because “Zimmerman” was often listed as a middle name for the Carpenter men. Turns out, it wasn’t a middle name at all – but a connection to their ancestry.

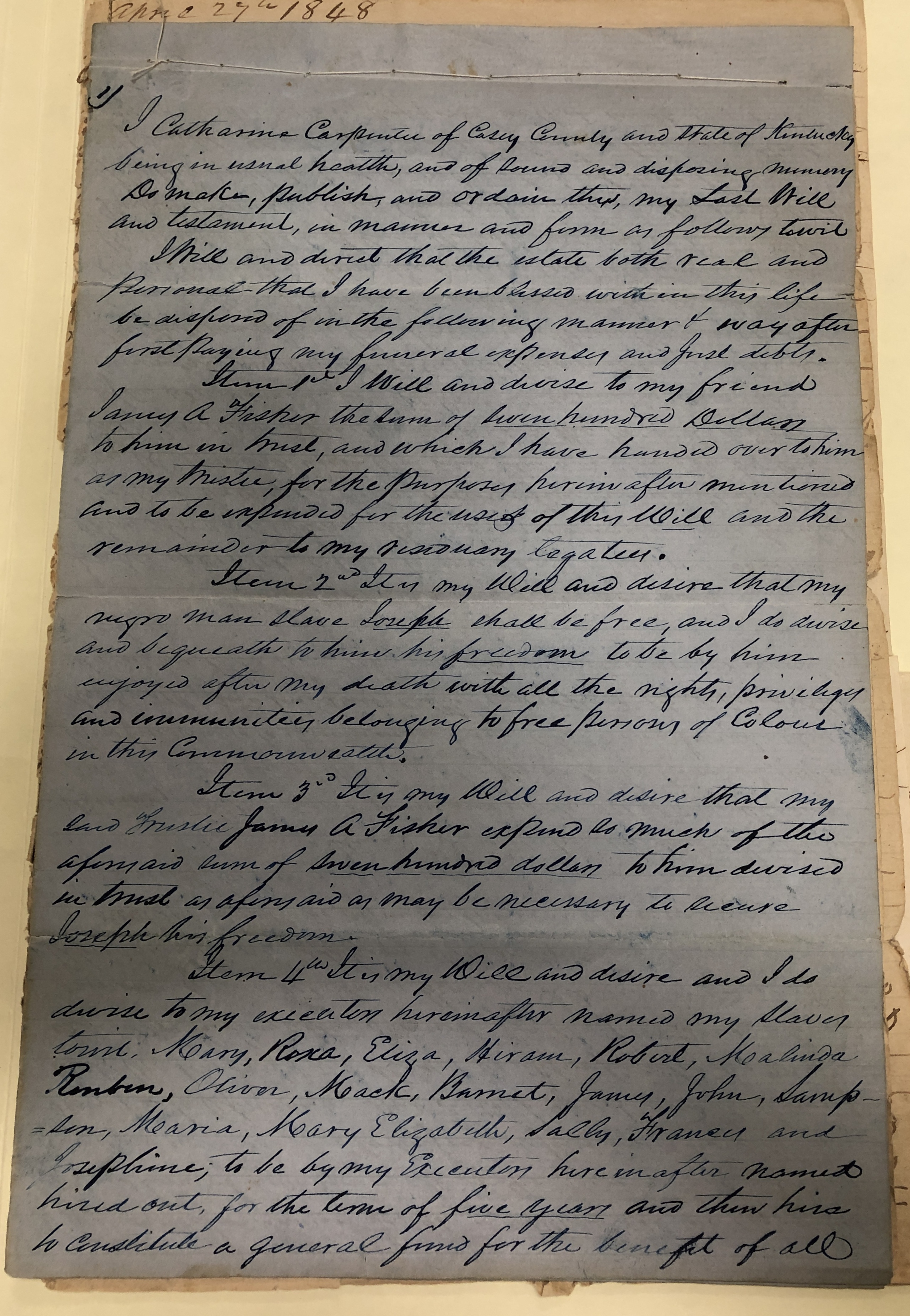

One of the greatest pieces of this collection is Catherine’s will. This original, handwritten document gives many details about her family and the enslaved members of her household. Contained within the document, Catherine lists her children and the spouses of her daughters:

By first husband, John Frye:

John Frye

Leah Frye married Jacob Carpenter

By second husband, Adam Carpenter:

William Carpenter

George Carpenter

Adam Carpenter

Conrad Carpenter

Henry Carpenter

Christiana Carpenter married 1st: Nathaniel Spraggins, 2nd: Daniel Funk

Margaret Carpenter married Shadrick Carter

Catherine Carpenter married William Dinwiddie

Sally Carpenter married Ephraim Cunningham

As for the enslaved members of her household: We know that Catherine’s father was a slave owner as was Conrad Carpenter (Adam and John’s brother) based on tax records, wills and the 1850 slave schedule. Moreover, John Carpenter left slaves to his heirs in his will while Adam Carpenter left his only slave to his wife, Catherine, at his death in 1806. Between 1806 and 1848, Catherine enslaved at least 19+ people. Our understanding of this enslaved group comes from a few sources. Her death predates the slave schedules of 1850 and 1860. However, Catherine kept very good records for the various working parts of the farm. In the case of the enslaved, she kept bills of sale, documenting her purchases over the years. Also, when a doctor was called in, there are notes that he treated enslaved members of the household.

The most telling piece of information we have regarding this group resides in Catherine’s will and subsequent documentation. In her will, Catherine stipulated that those enslaved members of her household were to be freed upon her death but under very strict conditions. The freedom was to be delayed for five years while they worked on various farms – or, were “hired out” – to raise enough money to pay for their transport to Liberia, or “any other African colony to which they may desire to emigrate”. Records kept by “Major” George Carpenter in a notebook dated 1837-1853 includes the hiring assignments and physical condition/doctor visits of these people who were almost free.

After five years, they (and any children born to them during that time) could either secure their freedom by buying passage to Liberia (or another African country) or remain enslaved and subsequently sold to the highest bidder. Her appointee, James A. Fisher, was to collect all of the money earned by the slaves during the aforementioned five years, and use that money to fund their emancipation and immigration to Africa. Unfortunately, there is no information as to what happened to any of the living slaves after 1853 (five years after Catherine died). Thus, we have not been able to determine if any of her former slaves immigrated to Africa.

Those enslaved named in her will and in the notebook recording their activities:

Mary

Roxa [Roxy]

Eliza – Died, April 1849

Hirum

Robert

Malinda – had 4 children

Reuben

Oliver

Mack

Barnet [Barnette]

James

John

Sampson

Maria

Mary Elizabeth

Sally

Frances

Josephine

Joseph – story below

Esther? – named in notebook only

There was one exception to this edict of removal, Catherine declared that her slave Joseph would be freed immediately upon her death. With that act of emancipation, he was to be given ownership of one horse of his choice from her stock, and the use of one land parcel to farm for the rest of his days. After his death, the land would revert back to her heirs. The action to free Joseph was entrusted to Fisher who was given $700 to ensure Joseph’s freedom was secured through the court system. At the time of her death, owners had to put up $500 in funds to ensure the newly freed would not become burdens of the county. With the money and the land used for sustaining a livelihood, Catherine believed this would be enough for Joseph to survive. At the time of this article, no evidence has been found regarding Joseph’s fate.

About the Authors:

Cheri Daniels, MSLS, is the Head of Reference Services for the Martin F. Schmidt Research Library and Editor of Kentucky Ancestors Online at the Kentucky Historical Society. She holds a B.A. in History and an M.S. in Library Science, both from the University of Kentucky. For over 20 years she has worked in various types of libraries, including 11 years at the University of Kentucky, and 8 years at KHS. She is also a contributing author to the 2018 book from McFarland Publishers: Genealogy and the Librarian. Other roles include: DAR Member, blogger at Genealogy Literacy, Journeys Past, and speaker on the regional/national stage (FGS: 2017, NGS: 2012/2014/2019, RootsTech: 2014/2019/2020, Mysteries at the Museum: 2014, WTVQ Kentucky History Treasures: 2014, 2016)

Cheri Daniels, MSLS, is the Head of Reference Services for the Martin F. Schmidt Research Library and Editor of Kentucky Ancestors Online at the Kentucky Historical Society. She holds a B.A. in History and an M.S. in Library Science, both from the University of Kentucky. For over 20 years she has worked in various types of libraries, including 11 years at the University of Kentucky, and 8 years at KHS. She is also a contributing author to the 2018 book from McFarland Publishers: Genealogy and the Librarian. Other roles include: DAR Member, blogger at Genealogy Literacy, Journeys Past, and speaker on the regional/national stage (FGS: 2017, NGS: 2012/2014/2019, RootsTech: 2014/2019/2020, Mysteries at the Museum: 2014, WTVQ Kentucky History Treasures: 2014, 2016)

Deana Thomas, MSLS, has served as the KHS Archivist for the past few years and holds an M.S. in Library Science, from the University of Kentucky. Deana’s main responsibilities include preparing archival collections for use and promoting them to academic and general audiences. When Deana accompanied the 1792 Kentucky Constitution to a joint legislative committee, she saw how excited people were about the document, holding it and taking selfies just like they were with a celebrity. “In this ever-changing world, it’s easy to look forward and forget the things of the past,” she says, “but it’s moments like seeing people thrilled by the 1792 Constitution that solidify the idea that what we are doing is still important and matters.”

Deana Thomas, MSLS, has served as the KHS Archivist for the past few years and holds an M.S. in Library Science, from the University of Kentucky. Deana’s main responsibilities include preparing archival collections for use and promoting them to academic and general audiences. When Deana accompanied the 1792 Kentucky Constitution to a joint legislative committee, she saw how excited people were about the document, holding it and taking selfies just like they were with a celebrity. “In this ever-changing world, it’s easy to look forward and forget the things of the past,” she says, “but it’s moments like seeing people thrilled by the 1792 Constitution that solidify the idea that what we are doing is still important and matters.”

[i] Sweet/Sour Mash Whiskey Recipes [Receipts]. Carpenter Family Papers, 1780-2003, MSS 47, Kentucky Historical Society; Box 1 FF17.

[ii] Ibid, George Spears documents, Carpenter Family Papers; Box 1, FF 1.

[iii] Virginia Land-Office Treasury Warrant, number 242, George Spears, Virginia Patent Series, 1779, Kentucky Secretary of State Land Office website, accessed July 9, 2019.

[iv] Ibid, Adam Carpenter Estate, Carpenter Family Papers; Box 1, FF 7.

[v] Ibid, Catherine Carpenter Receipts/Bills, Carpenter Family Papers; Box 1, FF 12.

[vi] Ibid, George Spears documents, Carpenter Family Papers; Box 1, FF 1.

[vii] Ibid, Catherine Carpenter Estate, Carpenter Family Papers; Box 1, FF 14.

[viii] Kentucky Tax Books – Casey County, Microfilm (1809-1848). Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort, Kentucky, Entry for “Catherine Carpenter”, 1845; North Side Green River, pg. 3.

Catherine Spears was born in Virginia about 1760 to German immigrants, George and Christina (Hardwin) Spears.[ii]

There is no proof that George Spears’ wife is a Hardwin. Indirect evidence supports his wife being a Froman.

The estate of John Fry, lists Paul Froman.

George Spears deeded land on Linville Creek, Rockingham (Augusta), VA, from Paul Froman Sr in 1756, under market value.

Paul Froman Sr was also moved to Lincoln County and died there in 1783.

Have found no records of the “Hardwins”