Using Historical Newspapers to Solve a Genealogical Mystery

By Kathy Reed

My grandmother was secretive. Ask her how old she was. No definitive answer. What is your wedding anniversary? No answer for that, either. I remember one whispered conversation among older members of my family questioning whether or not my grandparents, parents of five children, were ever legally married.

More than 30 years after her death, I became interested in genealogy. I took the advice given to all new genealogists and contacted my still-living aunts, uncles and older cousins. Count me among the fortunate few who inherited notes that provided some clues about my paternal and maternal families.

I called my cousin, 16 years my senior, and told her of my plans. Imagine my surprise when the first thing she said was, “Don’t be surprised if you find out the person we’ve always been told is our grandmother’s father is not.” What? I pressed her for why she thought that, and she said she had some conflicting records. She told me that whenever her mother asked for an explanation from our grandmother she would get this reply: “Haven’t I ever told you about that? Well, someday I will.” And of course, “someday” never came.

What We Had Been Told

My grandmother, Norine Cronin Jones, was the daughter of John Cronin and Lucy Probert. She was born March 27, 1884 in Mt. Sterling, Montgomery Co., Kentucky, the youngest of six children. Not long after Norine was born, Norine was “sent to school” in Lexington because “her mother was ill.”[1] I knew that Norine was living in Cincinnati as a young adult where she met and married my grandfather. Several of her siblings were also living in Cincinnati and northern Kentucky and shared normal family relationships. I had no idea what happened to her parents. There was no mention of either of their deaths in the paperwork passed on to me.

My cousin shared the documents she had that listed Norine’s father as William Dailey vs. the John Cronin we all “knew was her father.” As a new family historian, little did I know that it was going to take 11 years and every skill I could muster to solve this mystery. I started with the obvious.

The Evidence for John Cronin

- John Cronin and Lucy Probert are listed in the 1880 Census as the parents of four children: Joseph, Albin (Albert), Charles, and Annie.[2]

- The 1908 Cincinnati City Directory lists my grandmother as Norine Cronin, working as a hat check clerk at 17th W. 5th Street.[3]

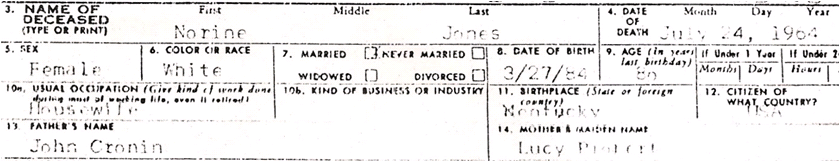

- Norine’s Death Certificate in 1964 lists her father as John Cronin and her mother as Lucy Probert.[4]

- Norine’s Death Notice appearing in the Cincinnati Post & Times Star lists her name as Norine Cronin Jones.[5]

Without my cousin’s contradictory records, it looked like a pretty open and shut case. But who was William Dailey?

The Evidence for William Dailey

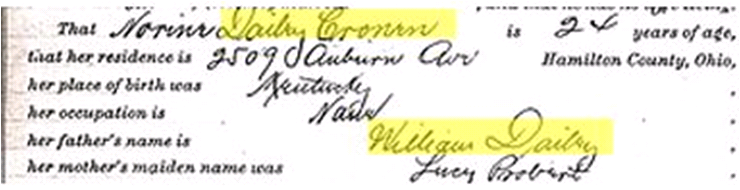

- When my grandmother filed for her marriage license to my grandfather, Charles F. Jones, she listed her name as “Norine DAILEY CRONIN.” Even more surprisingly, she listed her father’s name as William Dailey.[6]

- They were married at St. Rose Church (putting rest to the whispered questions as to whether they had been married) where they Church record lists the marriage between “Jones and Dailey.” Again, her father is listed as William Dailey.[7]

- The Baptismal Certificate for their first-born daughter, Edith, states that she is the daughter for Charles F. Jones and Norine Dailey.[8]

- The Marriage Certificate for their daughter, Edith, also lists her parents as Charles Jones and Norine Dailey.[9]

So who was William Dailey? I found William (AKA Billy) listed in the 1880 Census. He was a young man living with his older sister, Ellen. The Cronins and Daileys must have been close. I was able to located baptismal certificates for two of the Cronin children, and older sister, Ellen, was the Godmother of one of their children.

My first clue was when the Archives of the Diocese of Covington was able to provide me with a copy of an admission record to a northern Kentucky Catholic Orphanage for the first five children of John Cronin and Lucy Probert. In addition to the four children listed in the Census, a daughter, Addie, had been born to this couple in November of 1880. A separate record for the two boys also had this listing – “Father dead.”[10] The older children were all admitted three weeks before the birth of my grandmother. So the obvious question was, “When did John Cronin die?”

I developed a working theory to explain the discrepancies listed in the records. My theory was that John Cronin died sometime between 1880 (when he was listed in the Census), and March 1884 when the children were admitted to the orphanage. Norine’s mother then married William Dailey. Norine chose to use the surname “Cronin” when she moved to Cincinnati as a young adult, at times living with her half-siblings.

To confirm this theory, I needed to do one of two things: 1) prove that John Cronin was dead at the time of Norine’s conception, or 2) find a marriage record for Norine’s mother, Lucy, and a second husband, William Dailey.

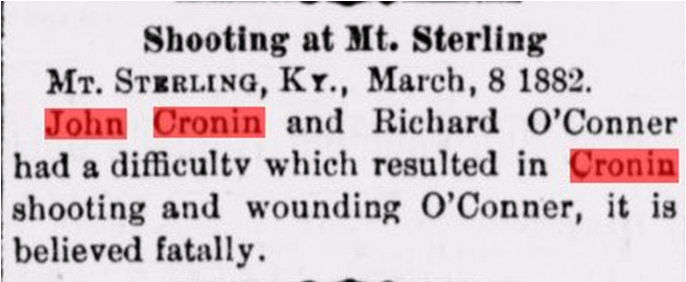

After nine years of searching, I found my answer . . . in historical newspapers. In 1881, the Millersburg, Kentucky Bourbon News carried this headline: “John Cronin Involved in Shooting.” Deputy Marshall Cronin had allegedly shot Richard O’Connor in the left side and arm inside O’Connor’s grocery store. As Cronin emptied his revolver, O’Connor threw weights with no effect.[11] A year later, the March 8th edition of the Maysville, Kentucky Evening Bulletin stated that John Cronin and Richard O’Conner “had a difficulty which resulted in Cronin shooting and wounding O’Conner, it is believed fatally.”[12] A Special Dispatch to the Cincinnati Enquirer listed a possible motive. “It is said there has been no good feeling existing between the parties for some time, as Cronin accused O’Connor of insulting his wife during his absence last fall.”[13] The Mr. Sterling paper The Democrat stated that “on this day they (Cronin and O’Connor) collided on the street and both turned and began an angry altercation, during which Cronin drew a pistol and fired at O’Connor five times, one ball taking effect in O’Connor’s left side, in the abdomen. “ It goes on to say that “The statements of the participants are so divergent that we cannot attempt to give any further particulars.”[14]

After nine years of searching, I found my answer . . . in historical newspapers. In 1881, the Millersburg, Kentucky Bourbon News carried this headline: “John Cronin Involved in Shooting.” Deputy Marshall Cronin had allegedly shot Richard O’Connor in the left side and arm inside O’Connor’s grocery store. As Cronin emptied his revolver, O’Connor threw weights with no effect.[11] A year later, the March 8th edition of the Maysville, Kentucky Evening Bulletin stated that John Cronin and Richard O’Conner “had a difficulty which resulted in Cronin shooting and wounding O’Conner, it is believed fatally.”[12] A Special Dispatch to the Cincinnati Enquirer listed a possible motive. “It is said there has been no good feeling existing between the parties for some time, as Cronin accused O’Connor of insulting his wife during his absence last fall.”[13] The Mr. Sterling paper The Democrat stated that “on this day they (Cronin and O’Connor) collided on the street and both turned and began an angry altercation, during which Cronin drew a pistol and fired at O’Connor five times, one ball taking effect in O’Connor’s left side, in the abdomen. “ It goes on to say that “The statements of the participants are so divergent that we cannot attempt to give any further particulars.”[14]

The Trial

Two days after the shooting, the Police Court was occupied with trying to determine whether or not John Cronin wounded Richard O’Connor with intent to kill. After examining several witnesses on both sides,”[15] the Court adjourned the house where the wounded man is staying. He was very feeble and could scarcely give his testimony.” Although Mr. O’Connor was not in any immediate danger, the doctors felt that he still could have “serious trouble.” When the Court reconvened, the Judge that there was sufficient reason to hold John Cronin to await the action of the Grand Jury, but he lessened the charge to “unlawfully shooting,” stating that he did not believe that “malice aforethought” had been proven. Bail was fixed at $300, which was provided, and John Cronin was now free on bail.[16]

But Wait . . . There’s More!

As if John Cronin had not been responsible for enough turmoil for his wife and five young children, the Mt. Sterling Sentinel Democrat reported that John Cronin had committed suicide! The circumstances offend the sensibilities of a 21st century reader. In an article entitled “In the Jaws of Death” we read:

After supper he said to his wife that he had the blues and was going up town to get drunk. She begged him not to do so, and replied that if she would send up and get him some morphine, he would stay at home and go to sleep. She sent him up and got him two grains of this narcotic which he took after he had washed and dressed himself. He lay down on the bed. Calling his little son to him he said ‘come lay down on the bed here, for it is the last time you will ever sleep with your father.’ They nestled up together and lay there for about five minutes, when Cronin petulantly observed that the morphine was ‘no account’ and that he would have to get more before he could sleep. He then got six grains more which he took, this being the fatal dose. This was at a few minutes after nine. He fell over on the bed and his wife, suspecting that he had taken an overdose, sent immediately for Drs. Thornly and Glover, who labored with him faithfully but to no avail, for he died at 25 minutes past 10 o’clock.[17]

Buried Three Times – At Least!

Lucy Probert Cronin had just lost her 33-year old husband and father of her children. Although Lucy was not Catholic, her husband was. In keeping with Catholic tradition, Lucy sought to have her husband buried in the local St. Thomas Cemetery. In a Special Dispatch to the Cincinnati Enquirer from Paris, Kentucky dated April 9, 1882, it states that, “They wished him to have Catholic burial and brought the body to the church at Mount Sterling where it was refused admission by Father Jones on the grounds that Cronin was not a practical (sic) Catholic and had committed suicide, the Catholic burial of which is forbidden by the Canon Law.”[18]

Lucy Probert Cronin had just lost her 33-year old husband and father of her children. Although Lucy was not Catholic, her husband was. In keeping with Catholic tradition, Lucy sought to have her husband buried in the local St. Thomas Cemetery. In a Special Dispatch to the Cincinnati Enquirer from Paris, Kentucky dated April 9, 1882, it states that, “They wished him to have Catholic burial and brought the body to the church at Mount Sterling where it was refused admission by Father Jones on the grounds that Cronin was not a practical (sic) Catholic and had committed suicide, the Catholic burial of which is forbidden by the Canon Law.”[18]

The body was then brought to this city (Paris) and it was refused Catholic burial here by Father Barry, notwithstanding the Cronins own a lot in this cemetery. The body lay above ground while a telegram was sent to Bishop Toebbe, which upheld Father Barry in his course. The body was then buried in the unconsecrated portion of the cemetery.

Last night five men came from Cynthiana and took up the corpse and buried it in the Cronin lot, finishing by daylight. The sexton saw the men at work this morning and reported the fact to Father Barry, who will either have the body removed at once to his first place or initiate suit in this April Term of Circuit Court.[19]

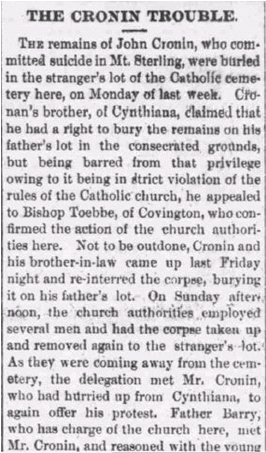

The Paris, Bourbon County, Kentucky Semi-Weekly reported:

Cronin’s brother, of Cynthiana, claimed that he had a right to bury the remains on his father’s lot in the consecrated grounds, but being barred from that privilege owing to it being in strict violation of the Catholic rules of the Catholic church, he appealed to Bishop Toebbe, of Covington, who confirmed the action of the church authorities here. Not to be outdone, Cronin and his brother-in-law came up last Friday night and re-interred the corpse, burying it on his father’s lot. On Sunday afternoon, the church authorities employed several mean and had the corpse taken up and removed again to the stranger’s lot.[20]

Father Barry confronted John Cronin’s brother James as he returned to Paris, Kentucky once again planning on digging up his brother for the third time. Father Barry proposed that the money that was paid for the Cronin lot would be refunded upon the return of the certificate of purchase. The family could allow those “who were entitled to be buried on the consecrated grounds” to remain.[21]

The Mt. Sterling Democrat Sentinel reported that Cronin “cursed the entire congregation and defied any man to step from the crowd, numbering 80 or 90 men, to stand up before him, which polite invitation was, as a matter of course, declined.” The same article reported that it was thought that the body would be returned to Mt. Sterling for burial in the Protestant Cemetery.[22]

Another Motive for Suicide?

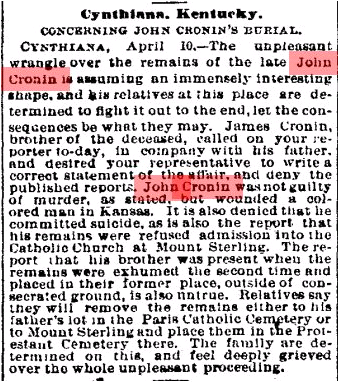

I thought my search was complete. I now knew that John Cronin could not have been my grandmother’s father. He committed suicide on April 1, 1882. Norine was born almost two years later on March 27, 1884. But the story didn’t end there.

I thought my search was complete. I now knew that John Cronin could not have been my grandmother’s father. He committed suicide on April 1, 1882. Norine was born almost two years later on March 27, 1884. But the story didn’t end there.

I assumed, initially, that John Cronin committed suicide because it looked like he would be serving time for the shooting of Richard O’Connor. But there was another possibility. In a Special Dispatch to the Cincinnati Enquirer, I learned that the shooting of Richard O’Connor was not his only difficulty. “It is stated that he (John Cronin) was also fearful of being arrested and taken to Kansas where last fall he had a difficulty with a Negro man and shot him.” We are also told that “he sometimes drank too much, but the past few days he had been sober and working in Storey’s confectionery. When dying, he stated that he was tired of living and did not wish to get well.” Unfortunately, his act left my great-grandmother, Lucy, “in destitute circumstances.”[23]

In the end, I was able to prove that William Dailey, and not John Cronin as so many records indicate, was Norine’s father. Proof came once again from the Archives of the Diocese of Covington. Norine was eventually placed in an orphanage, separate from her half-siblings, in northern Kentucky. The Archives was able to provide me with a copy of her baptismal record where it clearly states that she is the daughter of William Dailey and Lucy Probert.[24] However, William and Lucy were never married. In fact, William’s death certificate lists him as “single.” [25]

So where did William Dailey fit in? What happened to Lucy? How did Norine and her half-siblings reunite? Why was Norine so secretive? After all, she and my grandfather were married for 59 years. I’m proud to say that I have the answers to most of those questions . . . but that is another story.

About the Author

Kathleen Reed has been actively involved in tracing her family’s history for more than 12 years. She is a typical Cincinnatian with English, German and Irish roots and surnames to match. In addition to sharing her findings in genealogical journals, she has written about her family’s history in two blogs: Family Matters (http://jonesfamilymatters.blogspot.com) and A River Runs Through Us (http://ohioriverways.blogspot.com). She is currently serving as the Recording Secretary of the Hamilton County Ohio Genealogical Society.

Kathleen Reed has been actively involved in tracing her family’s history for more than 12 years. She is a typical Cincinnatian with English, German and Irish roots and surnames to match. In addition to sharing her findings in genealogical journals, she has written about her family’s history in two blogs: Family Matters (http://jonesfamilymatters.blogspot.com) and A River Runs Through Us (http://ohioriverways.blogspot.com). She is currently serving as the Recording Secretary of the Hamilton County Ohio Genealogical Society.

[1] Jones Family Record (MS, no date) privately held by Kathleen H. Reed, 9085 Shadetree Dr., Cincinnati, Ohio. Information in this document was supplied to Virginia R. Jones by Margaret Ann Jones Scardina, daughter of Norine Dailey Cronin Jones and granddaughter of Lucy Probert Cronin.

[2] John Cronin household, 1880 U.S. Census, Montgomery Co., KY, population schedule, town of Mt. Sterling, [ED] 76, [SD] 5, sheet 19, dwelling 168, family 190.

[3] Williams’ City Directory. (Cincinnati:The Williams Directory Co., Proprietors, June, 1908), p. 436.

[4] Norine Jones, death certificate no. 51723 (1964), Ohio Department of Health, Columbus, OH.

[5] Norine Cronin Jones death notice, The Post and Times Star, Cincinnati, Ohio, 25 July 1964, 11.

[6] Probate Court Marriage License/Marriage Record 1817-1983, volume 29, 184, Hamilton County, Ohio.

[7] Jones-Dailey marriage, 16 December 1909, St. Rose Catholic Church, Cincinnati, Ohio.

[8] Edith Jones baptism, 26 June 1910, St. Rose Catholic Church, Cincinnati, Ohio.

[9] Edith Jones marriage, 15 June 1932, St. Rose Catholic Church, Cincinnati, Ohio.

[10] Admission record for Cronin children to St. John’s Orphanage, Covington, Kentucky, March 1884 held by the Archives of the Diocese of Covington.

[11] “John Cronin Involved in Shooting,” (Millersburg) Bourbon News, 1881.

[12] “Shooting Affray at Mt. Sterling,” Special Dispatch to the Enquirer (1882, Mar 08). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/890326116?accountid=39387.

[13] “Dangerously Wounded,” (Mt. Sterling) The Democrat, 10 March 1881, Vol. 6, No. 16, p. 1.

[14] Ibid.

[15]“The Trial,” (Mt. Sterling) The Democrat, 10 March 1882, Vol. 6, No. 17, p. 2, col. 1.

[16] “Cronin’s Case,” (Mt. Sterling) The Democrat, 17 march 1882, Vol. 6, No. 18, p. 2, col. 1.

[17] “In the Jaws of Death,” (Mt. Sterling) The Sentinel Democrat, 4 April 1882, Vol. 6, No. 23, p. 2, col. 1.

[18] “An Unpleasant Wrangle: Over the Interment of John Cronin, A Suicide – Trouble Apprehended.” Special Dispatch to the Cincinnati Enquirer (1872-1922) [Cincinnati, Ohio] 10 Apr 1882: 2.

[19]. Ibid.

[20] “The Cronin Trouble,” (Paris, Bourbon Co., KY) The Bourbon News, 11 April 1882, Vol. 1, No. 11, p. 1, col. 2.

[21] Ibid.

[22] “Mr. Cronin’s Remains,” (Mt. Sterling) Democrat Sentinel, 14 April 1882, Vol. 6, No. 26, p. 2. col. 1.

[23] “By the Morphine Route,” Special Dispatch to the Enquirer (1882, Apr 04). Mount Sterling. Cincinnati Enquirer (1872-1922). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/890282898?accountid=39387.

[24] Sacramental Record for Baptism of Norine Cronin, December 1891. Archives of the Diocese of Covington, Kentucky.

[25] William Dailey, death certificate no. 1556 (1921) Commonwealth of Kentucky, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Frankfurt.

free sample simply need to have in mind that the

Great sleuthing and a fascinating story told well!

Thanks for this….wish you’d share how William Dailey fit in.

William Dailey is my grandmother’s biological father. According to his death certificate, he continued to live in Mt. Sterling as a single man his entire life and is buried in St. Thomas Cemetery near his older sister, Ellen.