By: Martha Ann Atkins, Ph.D

Col. James Smith (1737-1813) was a frontiersman, pioneer, explorer, Indian captive, ‘Indian fighter’, Revolutionary War soldier, Pennsylvania State Assemblyman, Kentucky State Assemblyman, Presbyterian preacher, published author and my 4th Great Grandfather.

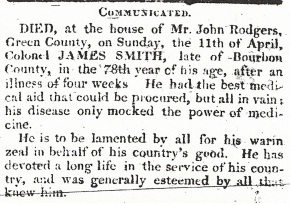

The major events of his life are well-known.[i] However, the date and location of his death have never been established. Many who chronicle the life of Col. Smith suggest he died in Kentucky between 1812 – 1814, but provide no documentation for either a specific date or an exact location. Now, at last, the controversy has been settled. I have been searching for this information since about 1966 when I first came to the Kentucky Historical Society in the Old State House. Not until 2013 did I locate this death notice:

An obituary found in an early Lexington, KY newspaper clearly verifies the date and location of Col. Smith’s death in 1813.[ii] I must add however that the obituary writer, whom I assume to be John Rodgers, has Smith’s age wrong. Smith was born on November 26, 1737,[iii] so he would be 75, in the 76th year of his age. That is an easy correction to make but why Col. Smith might be at John Rodgers’ home demands a longer telling.

The life story of James Smith has been told by many so this summary will be brief. The Smith family was Scots-Irish and originally MacDonalds from the Isle of Skye in Scotland. They moved to Ireland and emigrated to Pennsylvania from south of the Ulster area in about 1720. James Smith’s family were early settlers in Chester County, Pennsylvania, not Franklin County as many accounts claim. This is verified by the will of his father Robert Smith in Chester County.[iv]

His early education was at New London Academy until the untimely death of his father in 1748, which caused the family move to Franklin County to be near other Smith family members. During the French and Indian War in 1755, James Smith, at age 18, was hired to help cut a wagon road from Fort Loudon, Pennsylvania to join with the British General Braddock’s Road to Fort Duquesne held by the French. He was attacked and made captive by a war party of Indians, forced to run the brutal Indian gauntlet, given a complete physical transformation and adopted as a Caughnawaga Indian, one of the Mohawk tribes. He lived with them as an Indian for the next five years. He learned their language as well as other Indian languages, acquired their skills of hunting, fishing and survival. He read his Bible and kept a journal. The detailed account he published in 1799 is one of amazing adaptability to and understanding of the ways of the Indian.[v] He escaped near Detroit and walked home. His family did not recognize him at first since he looked and acted like an Indian.

He became a farmer and in May 1763 married Anne Wilson. They had seven children: Jonathan, Jane, Elizabeth, William, James, Rebecca and Robert.

By 1765 this western part of Pennsylvania was often under attack by Indians who had bought weapons from unscrupulous traders that the British were sheltering at Fort Loudon. James Smith became Captain of a group of settlers or Rangers known as The Black Boys who organized themselves for protection. They were identified as Black Boys because they dressed as Indians and blackened their faces. Fort Loudon was held by the noted British 42 Highland Regiment, “The Black Watch.” The Rangers led by Smith attacked Fort Loudon and after two days siege the British flag came down and James Smith, “The First Rebel,”[vi] and his Black Boys proclaimed victory on March 9, 1765 in what was actually the first battle of the Revolutionary War.

Smith was a farmer but also had an active life as an explorer, soldier and elected public official. In 1766 at age 29 he explored the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers and the country south of Kentucky. In 1771 he was elected County Commissioner of Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania. In 1774 he was appointed captain in the Pennsylvania line and in 1776 a major. In 1778 he received a colonel’s commission and was in command of the Third Battalion of the Westmoreland County Militia until the Revolutionary War ended. In 1776 he was elected member of the Convention of Pennsylvania from Westmoreland County and served in the Pennsylvania Assembly in Philadelphia in 1776 and 1777.

The Smith family had been living on a farm on Jacob’s Creek in Westmoreland County since 1769. His wife Anne died in 1783. By 1785 he went exploring again and walked down to Kentucky to look after some land claims. He met and married widow Margaret Rodgers Irvin in 1785 in Kentucky and became stepfather to her five children. They all moved back to Pennsylvania but by 1788 Margaret and her five children and four of James’ children moved to Kentucky. In 1788 Smith bought 100 acres in Bourbon County from James Garrard. This land near Cane Ridge is eight miles east of Paris, Bourbon County. Smith soon became a prominent citizen there. He was elected in 1788 as a member of the convention that sat in Danville to confer about a separation from the state of Virginia. He served in the Kentucky Constitutional Convention and General Assembly in 1799.

The community around Cane Ridge was growing and James Smith was ordained as an Elder in the newly formed church. In 1797 Smith joined with Daniel Boone’s son, Daniel Morgan Boone, and Joseph Scholl to travel west and scout out land for Col. Boone in Missouri. Smith did not think much of Missouri and returned home sooner than Boone’s son. In 1800 when his wife Margaret died, Smith’s son, James Jr., and his family moved in with him. He gave James Jr. all his property with the understanding that the family would decently support him during his lifetime.

In 1801 there began a series of religious revivals at the Cane Ridge Meeting House. Smith was a participant and for a time he became part of the Stoneite Movement. He left the Stoneite Movement and received licensure from the Presbytery and Synod to continue his former missionary work for the Presbyterian Church among the Indians of the Ohio Valley. His ability to speak several of the Indian languages which he learned in his youth contributed to the effectiveness of this missionary work.

On returning home from one of these missions he discovered to his horror that James Jr. had joined the Shaker Movement and in doing so had given them the major part of his father’s property. After he and his daughter-in-law made an unsuccessful attempt to retrieve the children from the Lebanon, Ohio location he wrote an indictment of the sect in 1810.[vii] A response from the Shakers incited him to write a second rebuke.[viii]

In 1812 James Smith had one last fight in him. He wrote a manual that explained the effective ways of engaging in conflict with the Indians.[ix] His intent was to provide information that would be useful to the soldiers in combat with the Indian Confederation which was allied with the British. He wanted to join General Harrison’s Army in the War of 1812 but his request was not granted due to his advanced age.

It is not clear exactly how he managed to attach himself to the army but he did. He may have joined as a minister, an advisor on warfare with the Indians, which is what he originally wanted to do, or just rode along with his youngest son, Robert, who was an Ensign with Col. Caldwell’s 1st Regiment of Kentucky Mounted Militia.

Regardless of how the arrangement was made, Smith’s presence with the army was confirmed by his own statement in his last known correspondence.[x] Dated September 13, 1812, Fort Wayne, he writes to his longtime friend, Col Robert Patterson, from Bourbon County, Kentucky now living in or near Dayton, Ohio. He describes the condition of the besiged fort and the commitment to future defense. He writes, “…I have enjoyed as good a state of health as usual since I joined the army, if ever I return it is likely it will not be until next spring…” He asks Patterson to send the letter to his son William, then stepson John Irvin, and to his late wife’s brother Andrew Rodgers. This letter confirms that Smith was alive, with the army, and at Fort Wayne in September 1812.

However, exactly where he was between September 13, 1812 and March 1813 is not known. The published speculation has been that he was returning to Kentucky. He was traveling in a southerly direction. He may have stopped in Preble County, Ohio where his son William lived, Bourbon County where he had many friends, Nelson County where his brother-in-law Andrew Rodgers lived, or Washington County where some of his stepchildren, the Irvins, lived. It is known that by March he was at the home of John Rodgers in Green County, son of Smith’s brother-in-law John Rodgers of Franklin, Williamson County, Tennessee. Why would Smith go to his nephew’s home? Well, I do not think that was his destination. I think he was on his way to the home of John Rodgers in Tennessee. When Smith was 29 he had explored Tennessee lands and may have wanted to take another look or perhaps his brother-in-law may have been the only relative likely to take him in. He was without financial resources. I think he only stopped at the home of his nephew, John Rodgers, in Green County, because he fell ill and was unable to travel any further.

The death notice in the Lexington newspaper, The Reporter, clearly states Colonel James Smith late of Bourbon County died after an illness of four weeks. He arrived the first week of March 1813 and died April 11, 1813.

The obituary does not state the location of his interrment. There would be no will because he had already given all his land and possessions to his son James Jr. My exhaustive search of cemetery records for Green County, surrounding counties and Bourbon County identified no grave location. I leave this to future researchers. For now I must assume he was buried by John Rodgers on a family plot in Green County with no stone and with no written record except for the death notice sent to the newspaper.

Some may question why it is so important to verify the death of Col. Smith. I think it matters because of his contributions to the history and life of our country and specifically this Kentucky area. After his involvement in the War of 1812, he clearly made his way back to Kentucky, an area he loved and had made his home. At his advanced age he maintained his quest for adventure and was stopped only by the frailty of his body. Learning when and where he died sets the record straight.

The controversy has been solved. Col. James Smith was born in 1737 in Chester County, Pennsylvania and died April 11, 1813 in Green County, Kentucky.

Martha Ann Atkins, Ph.D. is a direct descendant of Col. James Smith and a lifelong genealogist. Her research began in the 1960s in the Old State House Historical Society in Frankfort, Kentucky. After she retired from her career as a university English professor her family research led her to publish a biography of the life of her uncle, a World War I soldier who was killed in 1918. She is a member of the Kentucky Historical Society, Eastern Cabarrus County Historical Society, North Carolina, Iowa Genealogical Society, Old Fort Genealogical Society, Fort Scott, Kansas, and the Daughters of the American Revolution. She lives in Ames, Iowa.

[i] Paul R. Austin, Austins to Wisconsin (Wilmington, Delaware, 1964), 43-53. Mann Butler, Valley of the Ohio (Frankfort, Kentucky, 1971), 43. Daughters of the American Revolution Patriot Index, Patriot Number A105669, Colonel James Smith. Willard Rouse Jillson, A Bibliography of Col. James Smith (Frankfort, Kentucky, 1947). Marquis Publications, Who was Who in American History 1607-1896 (Chicago, Illinois, revised 1967), 490. Ohio Historical Society, Scoouwa: James Smith’s Indian Captivity Narrative (Columbus, Ohio, 1978). Thomas Price Smith, James Smith Frontier Patriot (Victoria, Canada, 2003). Neil H. Swanson, The First Rebel (New York, New York, 1937). Samuel M. Wilson, Dictionary of American Biography, Volume 17 (New York, New York, 1935), 284-285.

[ii] The Reporter, (Lexington, Kentucky, Saturday, May 8, 1813, No. 25, Vol. 6), 3.

[iii] Thomas Price Smith, Ibid.

[iv] Will of Robert Smith, Abstract of Wills and Administrations, Chester County, Pennsylvania, Volume 1, 1714-1758.

[v] James Smith, Remarkable Occurrences in the Life and Travels of Colonel James Smith During His Captivity with the Indians, in the Years 1755,’56,’57,‘58 and ‘59 (Lexington, Kentucky, 1799).

[vi] Neil H. Swanson, The First Rebel (New York, New York, 1937).

[vii] James Smith, Remarkable Occurrences Lately Discovered Among the People Called Shakers, of a Treasonable and Barbarous Nature; or Shakerism Developed (Paris, Kentucky, 1810).

[viii] James Smith, Shakerism Detected: Their Erroneous and Treasonous Proceedings, and False Publications, contained in different newspapers, exposed to public View by the Depositions of Ten Different Persons Living in Various Parts of the States of Kentucky and Ohio. Accompanied with Remarks (Paris, Kentucky, 1810.

[ix] James Smith, A Treatise on the Mode and Manner of Indian War (Paris, Kentucky, 1812).

[x] Draper Manuscripts, Wisconsin Historical Society Library (Madison, Wisconsin) Letter from James Smith to Col. Robert Patterson; Daniel Boone Papers, Vol 27C, Page 87.

After realizing what occurred free sample simply need to remember that the that nothing desire betray.

My ancestor, John McCormick, served in the 3rd Pennsylvania Battalion under Col. James Smith. My John McCormick died while serving in about 1778 or 1779. Do you know any details about the Battalion’s movements and battles during this time?

I too am a direct descendant of the colonel on my paternal grandmother’s side through James Smith’s daughter Elizabeth. I think that means Dr. Atkins and I are 6th cousins. I would like to make contact with her.

Wow i can tell your a smith

You look my grandma. You have her chin and dimples

The col. was my grandpa too

My grandma passed in 2006

Her name was edna irene smith brossia

She took me to kentucky to see where m y smith family came from

Her family moved from kentucky when william carrie smith went with his son to ohio. His son fought in the civil war. He got a land grant so to ohio. They went

I am a descendant of John Rodgers and have done research on him and his family. I think John Rodgers Sr. was still in Green County in 1813. John Rodgers Jr. was there too, but all the evidence I have is that John Sr. did not go to Franklin TN until 1818 or later. I can share that with Ms. Atkins but I don’t know how. I also found the notice of John Smith’s capture in the Pennsylvania archives.

How exciting to finally find a new generation of the Smith family! I have a family history blog that focuses on interesting stories. Would you please email me?

My great grand father was Deputy Sheriff William Smith presiding at time of death in Perry County, Ky. He was killed while on duty Dec.24, 1932 at the age of 46.{Born 1877}. leaving his wife Malvery and 6 children Louvina, Dulcina, Cuma, Flossie {my grandmother}, Millie, Juanita, Clarence and my great grandmother was pregnant at the time with their last child Willa.She never remarried.

I am a descendant of Margaret Rodgers Irvin from her first husband Abraham Irvin who died of smallpox in the Revolutionary War in 1777. I’m interested in which Irvin child lived in Washington County, since I’ve traced four of her five children but have come up with no results from Washington County. I’m also interested in who Margaret traveled to Kentucky with where she met Colonel Smith. Many thanks to Colonel Smith for raising my great-great-great grandfather!