By: Michael M. Wood

“Our Company saw two Indians in the wilderness; but we all got through safe”

William L. Farrow in a letter to his wife Betsy,

September 22, 1794

Kentucky in 1794 was still in the midst of war. The bloody defeat of the Kentucky Militia at the Battle of Blue Licks in 1782 was still vivid in the minds of many; in Kentucky alone more than 1500 pioneers had been killed or captured in Indian raids between 1784 and 1790.(1) Just a year prior, on Easter Monday at Morgan’s Station near Mt. Sterling, nineteen women and children were kidnapped, several killed and the survivors sold into slavery in the Northwest.(2)

Although the feared Cherokee leader Dragging Canoe had died two years earlier, the Chickamauga Wars continued under the leadership of Cherokee warriors such as Bob Benge and Chuquiiatague (Double Head). These men were fighting back against U.S. encroachment on their ancestral hunting grounds, and as such posed a very real threat to settlers in the greater Cumberland and along the Kentucky River.(3, 4)

The Holston Treaty of 1791 was an attempt to ensure “perpetual peace” between the United States and the Cherokee Nation.(5) Nevertheless, frontier conflicts between Indians and settlers continued. In June 1794, in an attempt to rectify misunderstandings about the Holston Treaty, the U.S. and Cherokee Nation signed the Treaty of Philadelphia. It was hoped that by clearly marking territorial boundaries, increasing the cash payment to the Cherokee Nation, and by stipulating penalties for the theft of horses(6), the terms of the earlier treaty could be ratified and an end brought to the fighting. However, by early September fears of war were again running high and rumors had started that the Creeks and Cherokee would strike again in the District of Mero.(7)

On 13 September 1794, just 9 days before William Farrow penned his words to his wife(8), 550 mounted troops from Kentucky and Tennessee had attacked the Chickamauga settlements at Nickajack and Running Water, killing 70 Indians including Chief Breath, and burned the villages to the ground.(9) This overwhelming show of force eventually lead to the signing of the Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse and a period of relative peace in the region.(10)

It was within this framework of hardship and uncertainty that a decade before, in the summer of 1784, the young William L. Farrow moved with his widowed mother from the comfort and safety of Loudoun County Virginia to the untamed frontiers of Kentucky.(11)

The Lexington settlement had begun eight years earlier and the Virginia General Assembly had formally chartered the town in 1782(12,13), but in perspective the pioneer population of Kentucky in 1783 was just 12,000 souls and skirmishes with the Indians were an ongoing problem.(14) Some Virginians certainly would have questioned the family’s timing, or even gone so far as to think such a move to be foolhardy, but opportunity is what drove many of our ancestors westward, and Col. William L. Farrow was no exception.

Early Life in Virginia

William Lycurgus Farrow4 (Joseph3, William 2, Abraham1) was born on 18 April 1771 in Loudoun County, Virginia. He was the eldest son of Joseph3 Farrow and Elizabeth Masterson, and grandson of William2 Farrow of Stafford County, Virginia.(15)

Although this article primarily profiles the life and times of one man, it is important to have a brief understanding of the extended Farrow family. As traditional in many families, a small number of given names appear repeatedly in each generation, thus a “William Farrow” might be seen multiple times in a single source record; but refer to different persons.

Abraham1 Farrow Sr., the family patriarch in Virginia, was a large landholder and tobacco grower in Stafford County (later to become Prince William County). By March 1691 he had married the widow Margaret Mason. They had the following children together; John, William2, Abraham, Mary, Lydia & Rose.(16) William2 Farrow was born before 1702 in Stafford County, Virginia; he and his wife Anne had the following children: John, Alexander, William3, Joseph3, Thornton, Anne, Lydia & Rhody.(17)

William3 Farrow, who will be referred to as “Capt. William Farrow” was born about 1739 in Prince William County, Virginia. William earned his title in the Revolutionary War, as a Captain in the Prince William County Militia.(18) He married the widow Sarah Triplett Tibbs but had no known children.

Joseph3 Farrow, the father of our subject Col. William4 Farrow, was born about 1742 in Prince William County, Virginia.(19) In about 1766 he married Elizabeth Masterson; they were living in Loudoun County, Virginia as early as 1769.(20) Joseph Farrow was a Patriot during the Revolution, having supplied wagons to the revolutionary troops in 1776.(21) Joseph and Elizabeth had the following issue(22), with the children’s first marriages listed(23, 24):

Mary Ann Farrow, born 1767; married John Harrow

Sarah Farrow, born 1769; married James O’Cull

William4 L. Farrow, born 1771; married Elizabeth Shores

Thornton Farrow, born 1776; married Henrietta O’Hara

Joseph M. Farrow, born 1778; married Elizabeth Waugh

Thomas Farrow, born 1780; married Nancy _____ (25)

Elizabeth Farrow, born 1783; married James Ross

Joseph Farrow died before 13 April 1784 in Leesburg, Virginia. At the time of his death he owned 2000 acres in Fayette County, KY.(26) Why William’s parents chose to name him after Lycurgus, the legendary Greek politician responsible for the legal reformation of Spartan society, is unknown. William however, by virtue of his public service as Sheriff, Justice of the Peace, Representative and Senator, as well as his work as an attorney, certainly lived up to his namesake. Our subject William4 Farrow is often referred to as “Col. William Farrow”.

The Kentucky Land Rush

The Transylvania Company was founded in 1775 to capitalize on the development of the central and western parts of Kentucky, and Daniel Boone was chosen to head a party of 31 axe men to clear a path through the Cumberland Gap. This Wilderness Trail was one of the major factors in the opening of Kentucky to new settlers. On 1 April 1775, Boone and his woodsmen began the construction of several temporary log huts, later to be known as Boonesborough.(27)

In the summer of that same year, two of William’s uncles, Capt. William Farrow and his brother Thornton Farrow, both of Prince William County, Virginia, set their sights on the preemption of land in what was soon to become Kentucky County. His father, Joseph Farrow, followed but a year later in 1776. As it turned out, the Farrow family’s decision to take lands in Kentucky would prove to be a large influence not only on Col. William L. Farrow’s life, but also on those of his descendants.

Initially, it was only possible to legally enter a claim for frontier land in Kentucky based on a military warrant issued to veterans or their heirs & assignees of the French and Indian War.(28) While the settlement rules became somewhat overlooked by incoming settlers, the system of awarding veterans land in return for service continued under the new American Government. The brothers Joseph, Thornton and Capt. William Farrow of Virginia all served as Patriots in the Revolutionary War. Capt. William earned his bounty rights through his Revolutionary War service in the Prince William Militia, initially as a 1st Lieut. under Capt. John Britt(29) and later as a Captain in the same organization.(30,31) His brother Thornton acted as an express to muster troops(32), while William’s father Joseph supplied “waggonage” to the troops of Hampton.(33, 34)

Joseph, Thornton and Capt. William Farrow each entered preemptions for 1000 acres; all of them recorded in early 1780 – Joseph with preemption number 865 on Licking Creek, 17 April 1780; Thornton with preemption number 979 on Buck Lick Creek, 24 April 1780; and William with preemption number 866 on Licking Creek 26 April 1780.(35)

Whether or not they were simply taking advantage of a war service bounty, or if they were fully caught up in the land rush of the times, the record shows that the Farrow brothers were responsible for at least two of the “40 or more improvements” made in the Hinkston and Licking region during the year 1775.(36)

According to the custom of the time, any person who marked off a tract of vacant land and made some sort of improvement on the claim had a legal preemption to that tract for a period of three years; during which the claimant was expected to survey and enter the tract, and pay the requisite fees in order to obtain a formal patent.(37) Many land disputes revolved around the question of whether in fact improvements had been made to preempted land, with depositions providing a detailed record of how the land was originally claimed.

On 23 July 1775, Elias Tolin joined a company with William Lynn and others at Fort Wheeling with the intention to come to Kentucky to improve land on the Ohio River. Near the mouth of the Little Kenhawa the company was overtaken by Thornton Farrow, Luke Cannon, William Bennett and others who informed that they were coming to Kentucky to take up lands for themselves and some gentlemen in Virginia. Thornton Farrow and a servant named Guy proceeded with the company to the mouth of the Kentucky and on to Leestown. George Rogers Clark joined the company here and the group “proceeded to Boonesville and thence to Somerset, camping at a place called Severn’s Lick”.(38)

The company of Thornton Farrow, John Crittenden, George Rogers Clark and others broke off from the group to make improvements at Buck Lick, later known as Grassy Lick, by deadening timber, marking trees and building a cabin. Patrick Jordan confirmed in a later deposition, “they encamped for the night and the next day came to this place and made an improvement by building a cabin which Thornton Farrow informed was made for his brother William Farrow.” Among this company was a man named Guy, who informed Patrick Jordan that he was “a hireling who came to this country for the purpose of improving lands for William Farrow of Virginia”.(39) Thornton Farrow and his company were absent from camp for several days and when they returned they reported that they had been making improvements. The next morning, Elias Tolin went down Somerset creek buffalo hunting and got lost from the company. He followed Grassy Lick Creek and found a burning campfire near the bank of the creek, but no persons nearby. Following a trail from the camp he came upon Buck Lick where he discovered a small cabin and the initials T.F. cut on a tree. A few days afterwards the company split up; with Farrow and Crittenden going ahead and the others following their trail back to Boonesborough three weeks later.(40)

Joseph Farrow came to Kentucky in 1776 with his brother-in-law, Richard Masterson and others with the purpose of the “improvement of the preemption in the name of Joseph Farrow”. On the land they “built a cabin for Joseph Farrow 30 poles below mouth of a branch now called Farrow’s creek and beginning of Joseph Farrow’s entry of 500 Acres made on a Treasury Warrant.”(41)

In December 1776 the Virginia General Assembly annexed Kentucky as a Virginia County. Until that point in time almost 318,990 acres of land had been entered in Kentucky; of this amount 190,850 acres had been entered on military warrants.(42) Boonesborough is located roughly between Mt. Sterling in the East and Lexington in the West; each about 20 miles from one another. In 1778 this was not a very attractive place to live, at least as recalled in Josiah Collins’s pension application; [when we came to Boonesborough in March 1778, we found] “a poor desolate and distressed people, without provisions almost, and with very little clothing, and what added most to their distress was their exposure to constant alarm from the Indians who were very troublesome. We had our meat to procure from the forest always in great danger of losing our lives”.(43)

Although we know that Lexington was not a place of note before 1779, Wm. McGee on a June expedition with Daniel Boone reporting “there was but one house”(44), but by the spring of 1780 things had begun to improve. Thornton Farrow was living in Lexington, his name being mentioned in an interview with Josiah Collins: “from the 17th of April 1779 to about the 1st of November 1784 I was in Lexington. In the later part of July, I went to Halifax County Virginia, and returned about the 1st of April 1780. On my return I found a number of emigrants, and a strong fort; which things had transpired during my absence. Timothy Payton, Joe Farrow, Thornton Farrow, Matthew Walker – young men had arrived from Virginia, & joined up, when I left for Halifax in July.”(45) In December 1781 Thornton Farrow is recorded as one of the original lot holders of Lexington.(46)

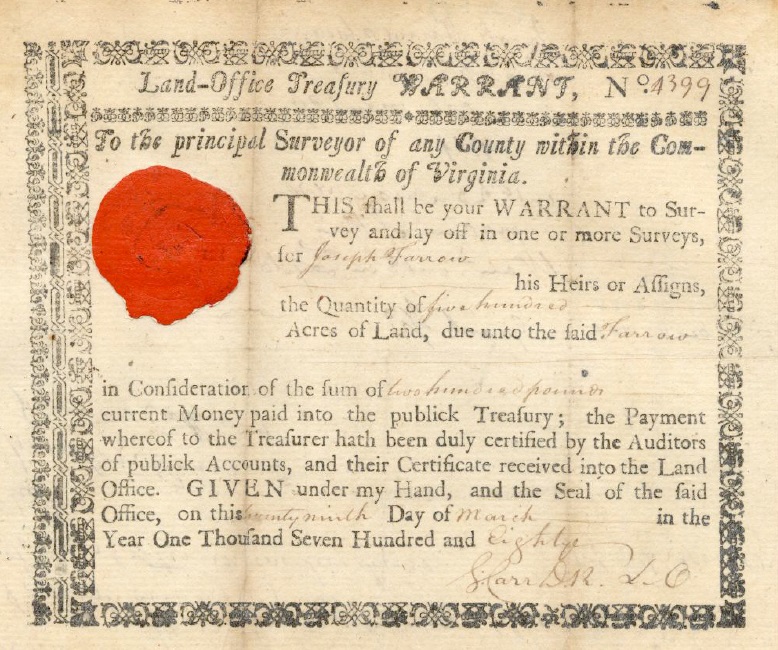

It was not long before William’s father, Joseph Farrow, took additional action. In an act approved May 1779 by the Virginia General Assembly, “whereas, there are large quantities of waste and unappropriated lands within the territory of this commonwealth, the granting of which will encourage the migration of foreigners hither, promote population, increase the annual revenue, and create a fund for discharging the public debt… be it enacted, that any person may acquire title to so much waste and unappropriated land as he or she shall desire to purchase, on paying the consideration of forty pounds for every hundred acres.”(47) Under this act, on 29 March 1780, Joseph Farrow purchased two Virginia Treasury Warrants of 500 acres each, numbers 4398 and 4399, at a total cost of £400.(48)

Joseph Farrow was clearly a wealthy man, as on 17 February 1780 he entered a preemption of another 1000 acres(49) adjoining the 500 acre Treasury Warrant, and on 10 April 1783 he invested an additional £4348 for the purchase of 2717.5 acres on Warrant 15426.0.(50) Between them, Capt. William Farrow, Thornton Farrow and Joseph Farrow had secured more than 6,000 acres of prime Kentucky land.

Statehood and the Great Migration

By 1784 word of the county’s rich soil and abundant water had spread far and wide; the lure of land on the Kentucky frontier – despite the hardships and risks – was unstoppable; some estimates being as many as 18,000 settlers moving to Kentucky in that one year alone, primarily from Virginia and North Carolina.(51)

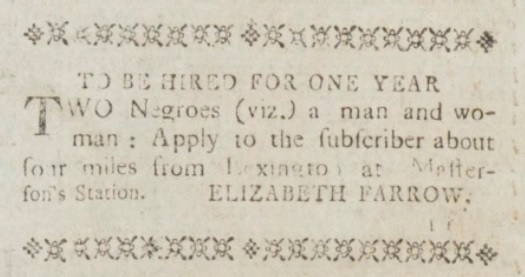

As the new decade approached, the population of Kentucky County continued its rapid growth. Nearby to his uncle Thornton in Lexington, Col. William Farrow’s widowed mother, Elizabeth Masterson Farrow, was living at Masterson’s Station, about four miles from Lexington. In a January 1789 issue of the K e n t u c k y Gazette, she advertised: “To be hired for one year, two Negroes (viz.) a man and woman” and requested that offers be addressed to her at Masterson’s Station.(52)

Col. William L. Farrow was acting as the business agent for his uncle, Capt. William Farrow, an absentee land owner and Inspector of Tobacco in Dumfries, Prince William County, Virginia.(53) The two 1,000 acre parcels on which he lived and managed were on Grassy Lick in Fayette County; the first of which Capt. William Farrow had patented on 4 November 1783(54), the second later patented to him as heir at law of his brother Thornton Farrow.(55)

By 1790 the population of Kentucky had surpassed 73,000 people(56), and residents wanted more autonomy from Virginia. In the scope of a few years, nine conventions on the matter of statehood had been held; eventually leading the residents of Kentucky County to petition Congress for statehood. In April 1792 the state constitution was ratified and in June of 1792, with Virginia’s blessing, Kentucky became the 15th state to enter the Union and the first state west of the Appalachians.(57)

Perhaps attracted by Kentucky’s new statehood, in September 1792 Joseph M. Farrow, Col. William Farrow’s younger brother, went to Grassy Lick Creek in the company of Anderson Bryant to build a cabin and make settlement on the lands of Capt. William Farrow.(58) Already living upon the land, with “several cabins and 8 to 10 acres of corn”, were Nathan Frakes, his son Joseph Frakes, John Tatman, John Robnet, William McCue and Daniel McGary; all of who were tenants of Capt. William Farrow.(59) Joseph Frakes and Col. William Farrow would go on to become lifelong friends.(60)

Clark County was formed from Bourbon and Fayette counties in 1792. Life in Kentucky continued to be both challenging as well as dangerous. As late as 15 March 1797, despite the Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse, Indians killed a family of 16 persons at Green River, as well as two men where the Wilderness Trail crosses Richland Creek.(61)

Both William Farrow and Elizabeth Farrow appear on the Clark County tax rolls of 1792.(62) This is clearly William’s mother, Elizabeth Masterson Farrow, as William did not wed until the following year.

Marriage to Elizabeth Shores

In 1793, William Farrow fell in love. His wife to be, Elizabeth Shores, is known from family letters to have been “very dark, and very beautiful”.(63) She was born 20 August 1775 in Fayette County, Kentucky(64), the daughter of Richard Shores and Susannah Simpson.(65)

Col. William L. Farrow and Elizabeth Shores were married on 8 March 1793 in Kentucky,(66) and over the course of twenty-six years raised the following ten children(67), with their first marriages(68) noted:

Col. Alexander Shores Farrow, born 21 April 1794; married Elizabeth Ringgold Taylor Nelson

Sarah “Sallie” Masterson Farrow, born 16 May 1795; married James Harrah

Joseph Davis Farrow, born 20 May 1797; married Ann Hood

Richard Shores Farrow, born 21 February 1799; married Mary “Polly” Nelson

William Lycurgus Farrow, born 11 August 1800; married Cassandra Philips

Valentine Champ Farrow, born 14 February 1804; married Lucinda Davis

Orson Dogan Farrow, born 15 February 1805; married Betsy Brewer

Jane “Jeny” Shores Farrow, born 17 July 1807; married John Hillis

Thornton Simpson Farrow, born 31 March 1809; married Susan Soward

Nimrod Fleming Farrow, born 3 November 1816; married Susan Summers

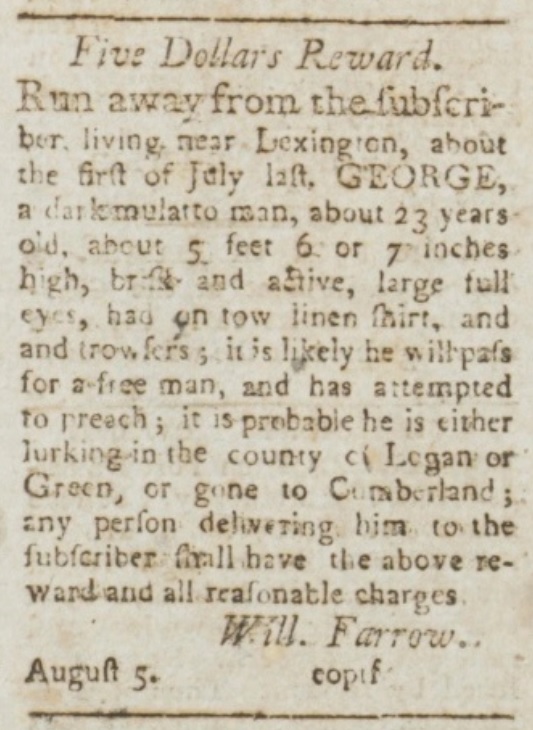

Although seldom mentioned in his own letters (69), multiple sources corroborate the fact that the Farrow family were in fact slaveholders. On 5 August 1797 William Farrow posted notice of a runaway slave, offering a five dollar reward; “Run away from the subscriber, living near Lexington, about first of July last, George, a dark mulatto man, about 23 years old, 5 feet 6 or 7 inches high, brisk and active, large full eyes, had on a tow linen shirt and trowsers, it is likely he will pass for a free man, and has attempted to preach, it is probable he is either lurking on the county of Logan or Green, or gone to Cumberland; any person delivering him to the subscriber will have the above reward and all reasonable charges.”(70)

As the Farrow family grew, so did Lexington and the surrounding area. In the year 1796 Lexington consisted of only 18 houses, but within ten years it contained more than 150, half of which were brick and built on a regular plan; the streets broad and crossing at right angles.(71)

Public Service in Kentucky

William Farrow turned 21 years of age in the spring of 1792. He was acting as a business agent, later as attorney, for his uncle Capt. William Farrow in regards to his land holdings in Kentucky. As was the practice in the 18th century, it was common for a man, so inclined, to obtain a legal education through self-study or an apprenticeship(72); the later traditionally ending upon one’s 21st birthday. Virginia in particular developed a successful system of educating lawyers by “reading law” in the offices of established lawyers.(73)

Within six years of moving to Kentucky, William’s interest in the law led him to an appointment as Sheriff in Montgomery County. He held this position as early as 1799, being responsible as an arm of the county courts to execute, for example, the court ordered sale of lands to collect delinquent tax payments(74), or even as one public notice documents, the sale of “a likely Negro man and woman, and four children, taken as the property of Duncan Campbell, to satisfy Joseph Guy on his debt and cost against said Duncan Campbell.(75) In 1804 was appointed to the position of High Sheriff of Montgomery County(76), the premier law enforcement role in the county.

The General Assembly of Kentucky, the legislative branch of state government, first met at Lexington on 4 June 1792. It was composed of 11 Senators and 40 Representatives elected from 9 counties. The first session ran for 12 days in June, the second session for 48 days in November. Members of either body received a salary of $1 per day.(77) Initially, seats in the House of Representatives were elected annually, and qualification was based on age and residency in the state and county.(78) In 1801 William was elected to the Kentucky General Assembly, representing Montgomery County in the House of Representatives; a position to which he was re-elected again in both 1810 and 1811.(79, 80, 81, 82)

Between his service in the General Assembly and his election to the State Senate the following year, he found time to act as a Justice of the Peace in Montgomery County; his work being mentioned in a public notice that James Suvel of Montgomery County had taken up two horses, their combined value appraised at $55.(83)

At the end of his 1811 term as a member of the House of Representatives, William decided to run for a seat in the State Senate. A seat in the Senate carried a four-year term.(84) William Farrow was elected as Senator representing Montgomery and Bath counties in the mid-year elections of 1812 – a critical time for the U.S., as the country was again at war with Britain.(85, 86)

In an 1812 letter to his constituents, he wrote in part: “To the citizens of Montgomery and Bath Counties: Fellow citizens, our session being closed, I deem it my duty as a representative of a free, enlightened and independent people, who has intrusted [sic] and honored me repeatedly, as a member in their state councils, to give them an account as far as the limits of a letter will admit, of the most important matters that have transpired during the present session of the General Assembly.”(87)

Those “most important matters” were varied indeed; from the war with Britain to the improvement of river navigation at home, from the establishment of new counties to acts for the relief of specific citizens, the General Assembly dealt with some rather unique issues; both forward-thinking and appallingly backwards. A review of some of the more interesting acts from the General Assembly term of 1811/1812(88,89) provides a unique insight into life in Kentucky at the time:

-An act to authorize the erection of a Turnpike gate on the road leading from the mouth of Triplett’s creek in Fleming County to the mouth of Big Sandy river, approved 15 January 1811; “the toll shall be as follows: person = 6 cents, horse mare or mule = 6 cents, carriage or cart with two wheels = 25 cents, carriage or wagon with four wheels = 50 cents, head of cattle = 3 cents, head of hogs = 1 cent. Post riders, children under 10 years of age, women living within 10 miles of the gate and every person picking salt from Little Sandy salt-works shall be exempted from the toll.”

-An act for the establishment of a mutual Assurance Society against fire on buildings in this Commonwealth; “Whereas from great losses sustained by the ravages of fire, it is expedient to adopt some mode to alleviate the calamities of the unfortunate who may suffer by that destructive element…be it therefore enacted that an assurance by establishment in Lexington, the Kentucky Mutual Assurance Society; the principles whereof that citizens of this state may insure their buildings and property against losses.”

-An act for the better regulation of the town of Lexington; “to assess upon each free male inhabitant above the age of twenty-one years, within the bounds of the town, a poll tax, not exceeding one dollar per annum, and also upon every male slave above the age of eighteen year, a like tax not exceeding one dollar per year. Trustees are further authorized to levy upon the property, real and personal (except male slaves above the age of eighteen years) such sum as them may judge necessary for the benefit of the town, not exceeding 25 cents for every hundred dollars of assessed value.”

-An act concerning the Lexington Library Company; “the directors of the Lexington Library Company may raise by lottery any sum of money not exceeding three thousand dollars, and that they shall be liable to the fortunate persons for any sum of money they may be entitled to in the said lottery. If the lottery is not drawn within three years, the persons purchasing tickets may recover the amount paid therefore.”

-An act for the more effectual preventing of crimes, conspiracies and insurrections of slaves, free negroes and mulattoes and for their better government; “be it enacted by the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky; Sec 1: That if any Negroes or other slaves shall, at any time hereafter, conspire to rebel or make insurrection, every such conspiring shall be adjudged and deemed felony, and the slave or slaves duly convicted thereof, shall suffer death. Sec 2: That where any slave or slaves, shall hereafter be convicted of administering to any person or persons, any poison or medicine, with the evil intent that death may thereupon ensue, such slave or slaves shall suffer death. Sec 3: That any slave or slaves, free Negro or mulatto, hereafter duly convicted of voluntary manslaughter, shall suffer death. Sec 4: That any slave or slaves, hereafter duly convicted of an attempt to commit a rape, on the body of any white woman, such slave or slaves, so convicted, shall suffer death.”

From the Senate; a resolution from Mr. Hawkins read: “Great Britain in her systematic course of injury towards our country; violence on the high seas, on the coasts of foreign powers, by capturing and destroying our vessels, confiscating our property, forcibly imprisoning and torturing our fellow-citizens, condemning some to death, slaughtering others by attacking our ships of war, and recalling those wanton cruelties that alienated us forever from her family… therefore it is resolved that this state feels deeply sensible of the continued wanton and flagrant violations by Great Britain and France of the dearest rights of the people of the U.S., as a free and independent Nation, that those violations if not discontinued and ample compensations made for them, ought to be resisted with the whole power of our country. Resolved that as war seems probable, that the state of Kentucky, to the last mite of her strength and resources, will contribute them to maintain the contest and support the right of their country against such lawless violations, and that the citizens of Kentucky are prepared to take the field when called on.”

This resolution, together with similar ones from other states, was sent to President Madison, who on 1 June 1812 recounted American grievances against Great Britain in a message to Congress. Although Madison stopped short of calling for a declaration of war, Congress voted for such and the conflict began formally on 18 June 1812 when Madison signed the measure into law.(90)

The War of 1812

As seen by the Senate resolution, emotions in the new conflict with Britain ran especially high. Many, including William Farrow, left their homes and careers to volunteer in the fight. Whether because of his family’s history as soldiers in time of need, or because of his seat in the Senate, William was given the rank of Captain; commanding the 1st Company of seventy-three men in the Third Regiment of the Kentucky Riflemen.(91, 92)

Exactly when William L. Farrow achieved the rank of Colonel is unclear, but it was prior to 1834, when he is profiled in a summary of military achievements at Fort Wayne in 1812.(93) In September of that year, Col. William Farrow led a company of mounted riflemen from Montgomery County to Fort Wayne in Indiana. Here, together with Col. James Simrall and his regiment of 320 dragoons armed with muskets, they were ordered by General William Henry Harrison to destroy the Miami Indian village of Little Turtle, some twenty miles northwest of the Fort. Harrison specifically gave the men orders not to molest the buildings formerly erected by the United States for the benefit of Little Turtle, whose friendship for the Americans had been consistent after the treaty of Greenville in 1795. The men left Fort Wayne on 18 September 1812 and on the following day proceeded to the Eel, wiping out crops, burning the village as well as the trading post and pushing the Miami downstream to a point near Paige’s Crossing. The great Chief Little Turtle had died two months prior, and although his home was spared, his son Black Loon was killed in the fighting.(94, 95)

Additionally, in 1813, William served as First Major in the 2nd Regiment of the Kentucky Mounted Volunteer Militia commanded by Lieut. Col. John Donaldson, and was present at the Battle of Lake Erie, where Perry’s decisive naval victory over the British gave the U.S. control of the lake; a turning point in the war.(96)

In a short summary of his military career, written in 1838, Col. William L. Farrow was described such; “His statue is five feet ten inches, his form strong and expanded, his manners conciliatory and popular, his mind active, enquiring, discriminating and energetic. Hence the part he has acted among his contemporaries has been rather conspicuous. He participated in the Battle of Thames under Gen. Wm. Harrison on October 5, 1813, when the United States Army vanquished the combined forces of the British and Indians, capturing nearly all the former and compelling the later to fly. In this battle Tecumseh fell. Col. Farrow filled several militia offices creditably and received a General’s commission, to which he never qualified on account of leaving Montgomery for Fleming County.”(97)

Although William Farrow apparently survived the war without injury, he did have some trouble with his horses – both of which he owned. In an effort to be compensated by the government he swore in a later deposition; “About the 15th of September 1813 at the mouth of portage on Lake Erie I was ordered to leave my horse and take water portage to Canada. I did so and when I returned to portage I could not find my horse.” The government agreed to pay William $75.00 for his loss. In a second deposition he swore; “When in Fort Wayne I was taken sick and having no forage for my horsebeast she was let loose in a stock field at Fort Wayne and by some means got her foot in the rope which was round her neck (for the use of tying up) and croaked herself to death.”(98) The government refused to pay for the accidental death of his second horse, although they did grant William Farrow a Bounty Land Claim, number 14885-160-55, which was issued to his widow, Nancy Davis Farrow.(99)

Post War Fleming County

After serving in the Senate, William transitioned into the life of a farmer, moving with his family to live on the land earlier preempted by his father in Fleming County.(100) Fleming County was established in 1798, from part of Mason County, with the Licking River marking much of its western boundary and Flemingsburg as the county seat. In 1800 the population of Flemingsburg was only 124 persons.(101)

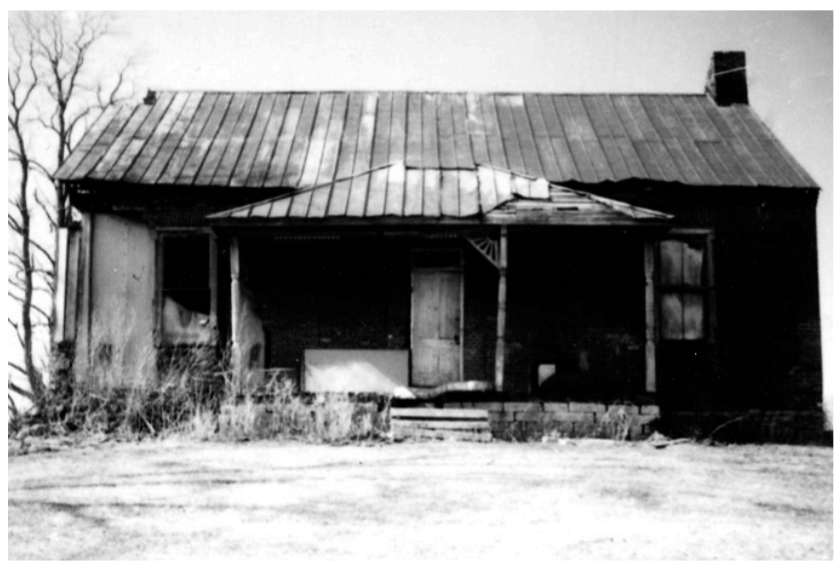

In 1818 William built a brick home on the property, the walls of which were 5 bricks deep, the bricks being made nearby. It had a basement with a dirt floor, a back door, and a hand-cut fieldstone foundation, the stones of which fit very closely together. The family cemetery is located about 100 yards from the former site of this house. Although damaged by a hurricane, the home was still standing in the 1970’s when the last known photo was taken; however the floorboards were badly deteriorated and the building unsafe to enter.(102) Clearly it was difficult work and financially challenging to be a farmer in early Kentucky.

Much can be garnered about William’s life in the county via the letters he wrote to his oldest son Alexander in the initial years after moving to Fleming County. William’s letter reads; “I find that I can get a number of hogs by giving $3.50 per Lb Wt. with 10 cents extra for each hog, the money to be paid on delivery of the hogs. If you have not made an engagement I wish you to try and make one. I still think that any of the purchasers will give $4.00 per Lb and 25 cents for each hog to get 200 head or upwards at one place. I know that you will make the best bargain for me that is in your Power. I still want as late in October for the delivery as you can get, and Kentucky notes would be preferred.” A year later William is buying wheat, and in need of Ohio notes for payment, “I have purchased some wheat for which I Promised payment shortly. If it is in your power to let me have some money it will be of great use to me at this time. Ohio Bank paper will answer as well as any that of the Charter Banks.” (103)

In 1818 a public road was planned to pass though William’s land, an issue about which he was very concerned, but one which also shows his strong understanding of the law. He wrote; “My Son, you inform me that there is an intention of some people to have a road through my Land and very much to the injury of my property. I am very much opposed to having a public road through my Land as it will tend to divide and detach the Land in such a manner that will reduce the value if I wish to sell or improve. Therefore I shall make all the opposition to a road that is in my power as I cannot see any public benefit arising from a road in that direction. If there should be an application to Court for Viewers you will object in my name. If Viewers returns the road they must state that I object to it. Of course I must be summoned to show my Objections to the road. No damage will make me willing for the road and I think when the persons wishing the road are informed that they will have to pay the damage their order for the road will cease. If there is an attempt made you will please to write me by mail and I will Impower you to prevent it if it is in your power.”

Later that same year the issue turned to land purchases, William advising his son; “Mr. Marshall will sell 2000 acres if he can get one half of the money in hand. You must let me know if you can sell and on what terms for if I can make a trade with Marshall I will buy all his Land if I can make payment. But my son you had better not be in too much haste to sell your land. If people takes up on idea that you are compelled to sell you will lose very much in the price. You had better look out and see a certain plan to go to before you make sale. Mr. Marshall proposes to sell but he will not sell less than 2000 acres and there is not much improvement on it and the greater half is Oak Land which would make the price too great. Jo Harrow says there is Plantations for sale nearby. You had better spend a few days and look over that and other parts as you might be very much put to it if you was to sell with out knowing where you was a going to. I have sent two sum money you must if it is in your power send them to me in the next week as all the party will be summoned but Josephs F., Thos. & Charles has none. Jo Harrow has the subpoenas if he don’t do the business you must though.”

The state-chartered bank panic of 1819 was the first major post-war financial crisis; the ensuing recession heavily depressed the U.S. economy for several years. Farming clearly had its challenges, as in 1821 William as well seems to have fallen on hard times. In a letter to Alexander he says; “I want you to send mother money. It is getting very hard times with me about money and I fear that the worst is not come. The money that was allowed to Fleming County is all borrowed out at the Bank and applications for five times as much as came to the dividend of the county of the money that has been received. My fears are still that half of the applicants to the Bank will not be supplied. If I could keep my waggon at work I could make something that way but my horse is so wasted I don’t know how I shall make it out. Old Rock is dead, Tom and Ball are lame so that I have not horses to work at home and go in the wagon. If you have any spare horse that would do to plow I would be glad to borrow one of you for a while.”

William’s uncle, Thornton Farrow, had died in September 1808(104), and his uncle for whom he had been acting as a business agent all this time, Capt. William Farrow, died a few years later. Although Capt. William Farrow was married to the widow Sarah Triplett Tibbs in 1796, as can be seen in a 4 February 1796 deed from “William Farrow and wife Sarah, of Prince William County” to Simon Luttrell as executor of William Carr’s estate, he died childless. (105) (106) There is a mention of an “adopted son” in a family letter, but in an 1845 land case deposition, it was supposed that this was an illegitimate child.(107) Capt. William Farrow’s obituary appeared in the Kentucky Reporter a month after his death; “William Farrow of Fleming County died October 17, 1819, aged 80 years, and is buried in the old Farrow cemetery in Mason County”.(108)

That there was some uncertainty about Capt. William Farrow’s estate planning can be seen in two depositions that were taken to confirm his intentions. In a deposition of 6 June 1842, Joseph M. Farrow confirmed; “the heirs of Capt. William Farrow are, as he himself always told me, Joseph Farrow, my father’s children.(109) In another hearing, Anderson Bryant, who was “intimately acquainted and often with inspector Capt. William Farrow” deposed that Capt. William Farrow “repeatedly and at different times” promised to “give and grant to his nephew Col. William L. Farrow son of Joseph Farrow one thousand acres of land” on the waters of Grassy Lick Creek in Montgomery County.(110)

Farrow versus Farrow

The Farrow family was no stranger to the courts; based on their frequency of filing lawsuits over land rights, they clearly enjoyed a good court battle. In addition to several suits with others, the family at one point took to suing one another over the ample land they owned.

One of the earliest inter-family lawsuits was in the 1738 case of “Farrow v. Farrow”, between the children of Abraham Farrow of Virginia. William2 as the defendant in a case was sued by his younger brother Abraham in regards to the land distribution from their father’s estate. On Abraham’s deathbed, William promised his father to convey a certain tract of land to his brother Abraham, however upon learning the details of his father’s will, which divided the lands evenly between the brothers, he decided against such an additional conveyance. The court dismissed the case, citing that a “man’s Intentions alone, without the Form & Ceremony which the law has appointed, is not sufficient reason for the Court to interrupt and impose the course of the law.”(111)

The land laws regarding pre-statehood preemptions required the claimant to have made improvements to the land claimed. In later years, when the preempted land became more valuable, challenges to ownership often arose. Showing proof of such improvements made, typically via the deposition of citizens of good standing, was a commonly accepted method of confirming ownership via the courts.

Legal notices about early preemptions abounded in the newspapers of the time. Questions about Capt. William Farrow’s land claims, and those of his brother Thornton, started as early as 1796. In several issues of the Kentucky Gazette newspaper, Capt. William Farrow posted Public Notices; one announcing that “commissioners appointed by the court of Clark, will attend on the twenty-second day of August next, on a preemption of 1000 acres, made in the name of Thornton Farrow, lying on Buck Lick Creek, a branch of the north fork of the fourth fork of Licking. On the same day they will attend on a preemption of 1000 acres, made in my name, adjoining the above.”(112)

In a 1797 public notice, Joseph Farrow Jun. wrote; “Whereas on the first day of April 1783, Joseph Farrow enters 1000 acres on the south side of the north fork of Licking to include his improvements, and also 500 acres by virtue of a treasury warrant on the waters of the north fork of the Licking, joining his preemption on the south-east side, and whereas the proof of said improvements depends on the oaths of persons now living,” …“that on the 18th of April next at the mouth of Farrow’s creek, commissioners appointed by the court of Mason County will meet to perpetuate the spot where the said improvements stood. Joseph Farrow Jun., Heir of Joseph Farrow, deceased.”(113)

Although Col. William Farrow had been Capt. William Farrow’s agent on the land since 1794, as time went he started selling the land for himself.(114) In “Farrow v. Edmundson”, this concept of “adverse possession”, namely obtaining title to another’s land by holding the property in a manner that conflicts with the true owner’s rights for a specified period, William’s right to sell the property was confirmed by the courts. In their ruling, the court wrote “a public claim by an Agent, to hold in his own right, selling parts of the land by conveyance and delivery over twenty years, is presumptive notice of an adverse holding.”(115) One of these parcels, a plot of 18 acres, had been sold in 1803 by William Farrow to William Nelson (116), an acquaintance whose daughter Mary ‘Polly’ Nelson would later marry William’s son, Richard Shores Farrow.(117)

That same year, when the next challenge was being fought in the public eye, Col. William L. Farrow was acting as “Attorney in fact” for his uncle, Capt. William Farrow. In several issues of the Kentucky Gazette he placed public notices that; “On the fifteenth day of November next, commissioners will meet at my house in Montgomery County, and continue from day to day until the business is completed, to take the deposition of witnesses to perpetuate their testimony, to establish the improvement called for in an entry of 1000 acres of land made in the name of William Farrow, on Grassy Lick, and to do such other things as may be necessary and agreeably to law.”(118) The matter took its legal course, with William’s next public notice being “I shall attend the commissioners appointed by Clark county court, at Tuesday the 20th of December next, at William Farrow’s improvement, on Grassy Lick, made in the year 1775, and then proceed to establish the specialty of said improvement and calls on an entry of 1000 acres of land, entered, surveyed and patented in the name of William Farrow; and do such other things as agreeable to law. Should the business not be completed on that day, will be continued from day to day by adjournment, until finished.(119)

In the case of “William Farrow v. Thaddeus Dulin”, filed 23 September 1809 in Fayette

Circuit Court, Col. William L. Farrow, acting as “Agent for William Farrow, Sen.”, filed a writ of injunction against Thaddeus Dulin who laid claim on 15 May 1780 to land which “interfered” with William Farrow’s 26 April 1780 right of preemption to the same land on the basis of “having obtained an earlier patent.”(120)

With that case won, and ownership of Capt. William Farrow’s original preemption finally challenge-free, the family took to suing each other over their deceased father Joseph Farrow’s land. The ensuing legal battle coincided with the death of Joseph’s wife, Elizabeth Masterson Farrow, in 1822. In the 30 August 1822 case of “William Farrow et al v. Joseph Farrow heirs”, Joseph M. Farrow, or “lazy Joe” as he was known within the family(121), sued his brother Col. William Farrow for the return of a parcel of land that had belonged to their father. Col. William Farrow stated that he purchased the disputed 1500 acres of land in Mason and Fleming counties in 1803 from his brother Joseph for 250 Pounds. A deed was drawn up, stipulating the return of the land if the money was repaid, and William took possession of the property. With no proof being offered by Joseph that he ever repaid the money, the court dismissed the case.(122)

In 1826 Col. William Farrow filed suit in Clark County Circuit Court, against members of his family, arguing that they were encroaching on a 120 acre parcel of his land. This case of “Farrow v. Farrow” was an ejectment by “William Farrow and others against Alexander S. Farrow and others”; William arguing that this parcel belonged to the two thousand acres he owned, via posthumous grant, as heir to Capt. William Farrow. The land granted to William was described as “two thousand acres on Grassy Lick creek in Montgomery County, part meadow, part corn land, and without any designation of boundary or special description to identify the precise tract.” The initial decision in the case went against William; to which he filed an appeal. The case was sent to the Court of Appeals and re-tried 19 October 1829 under Judge Robertson. The jury found a verdict for “the lessors of the plaintiffs, for five-sixth parts of 120 acres of the land, in the declaration mentioned, and embraced by the boundary in the deed from James Wren to William Farrow.

The deed from Wren to Farrow is for 120 acres and describes the boundary with precision. Wherefore the judgments of the circuit court, rendered subsequently to the first verdict, are reversed and set aside, and the cause remanded, with instruction to give judgment on the verdict.”(123) In a later letter, William recounts how he purchased the land from Wren for “a first rate waggon with four pair of good wagon sheet, a feed-trough & one or two horses”, later paying “four or five hundred dollars for a quit Claim title to James Wren for the Land.”(124)

“Lazy Joe” Farrow re-filed his original 1822 lawsuit against his brother William in 1841, and lost again. Joseph protested the verdict, and the case was referred to the appellate court. The Court of Appeals ruled in their Spring 1846 term that as no proof of re-payment could be shown, and while the case was appealed fully nineteen years after the fact, that the land indeed belonged to William.(125)

At the time of his death in 1846 Col. William Farrow left 543 acres to fifteen of his descendants; the land consisting of 3 adjoining parcels; 112 acres in Fleming Co. along Farrow’s Creek, 165 acres in Lewis and Mason bounded by Rezin and Matthias Davis, and 266 acres in Mason and Fleming corner to James Willett’s land. Even after his death, the family continued to fight over the land. His daughter Kerlinda Farrow and her husband J. Reed Wallingford sued the other descendants in the name of 11 minor children and won. At the April 1849 Fleming County Court term, the partition of lands on behalf of the plaintiffs was decreed, while William’s children and others, including J. R. Wallingford and his wife, released their interests in the land.(126)

In a final distribution of his land to Col. William L. Farrow’s heirs in Lewis County, not surprisingly in compliance with a lawsuit, there were so many heirs participating in the lawsuit that each received only 36 acres.(127)

Marriage to Nancy Davis

Col. William Farrow’s beloved wife “Betsy”, Elizabeth Shores Farrow, died in Fleming County on 5 September 1826.(128) With his ten-year old son Nimrod still at home, William remarried to Nancy Davis of Lewis County just over a year later. The ceremony was recorded in Fleming County on 2 November 1827.(129)

Nancy Davis, the daughter of Matthias Tyson Davis and Rachel Maynard(130), was already an in-law by marriage. Born 23 February 1797(131), Nancy was the younger sister of Lucinda Davis; the wife of William’s son Valentine Farrow.

In 1827 Nancy was 30 years old, William was 56. Considering her age, Nancy drove a hard bargain. A marriage contract dated 20 October 1827 and entered in both Fleming and Mason Counties states in part that she and William are about to marry, and that “William is father of a family of children by a former marriage. Nancy is to have all the estate now belonging to her, and life estate in 50 acres deeded to Wm. Farrow by Wm. Smith by order of Circuit Court of Mason County, lying in Mason County (bound by corner preemption of Joseph Farrow, dec’d, corner of dividing line between said Wm. Farrow Sr. and Sarah O’Cull (formerly Sarah Farrow), and Betsy Pollitt a tenant of Farrow. Wm. Farrow also promises to build for Nancy a brick house within a ten year period – same to be 36′ x 18′, with a fireplace in each end, and gives her a Negro girl, Rachel. If William Farrow survives, the above reverts to him.”(132)

William and his new wife wasted no time starting a family; their first child was born just 10 months after the nuptials. As with his first marriage, there were many children born to this union; the last being fathered when William was 68 years old. The seven children of William Farrow and Nancy Davis (133), with first marriages noted (134), are:

Kerlinda Davis Farrow, born 10 August 1828; married James Reed Wallingford

Elizabeth Masterson Farrow, born 24 August 1830; married James R. Bell

Matthias Davis Farrow, born 24 October 1831; married Sarah Goddard

Kenaz Maynard Farrow, born 24 August 1833; married Mary Margaret Wallingford

Nancy Hanson Farrow, born 2 September 1835; married John M. Terry

David Champ Farrow, born 17 May 1837; married Mary Graves

Benjamin Howard Farrow, born 24 May 1839; married May S. Bramel

These seem to have been particularly happy years for William, not only in his life with Nancy and his second family, but also in seeing the success of his children from his first marriage. In a particularly philosophical letter he wrote; “My Son Alexander S. Farrow, I received your letter dated the 8th instant by your brother Richard which gave me great satisfaction to hear that you and your family were in good health and were enjoying such peculiar favours from divine providence. Our hearts ought to overflow with gratitude at all times when we reflect how kind the LORD has been to us, separated as we are. At times it gives me very unpleasant feelings, but perhaps it is all for the better. As to our temporal affairs, you surely are in a situation far better for your children than you would have been if you had remained in this country. I hope and pray that you may live to see your children settled in the world and have the satisfaction to know that they are respectable and useful to society. I had rather see my progeny live and move in a state of mediocrity and be respected than to see them wallowing in wealth and ease without the good will of their fellowmen.”(135)

It was 1838, and this was one of William’s first letters to indicate his growing interest in religion.

The Second Great Awakening

William Farrow was a man of many letters. At the time, mail was carried primarily by hand or delivered on horseback; the first mail delivered by train was not until 1838. These letters, mostly delivered “through the politeness” of a friend or relative, span five decades from 1794 to 1844. From the words of a newlywed to the prices of livestock, from the personal advice of a father to the politics of the day, these letters offer us a unique view of life on a Kentucky farm and more specifically, as we will see, how the Second Great Awakening changed one man’s personal view of religion over time – as it did many of the citizens of Kentucky.

In the decades following the Revolution several evangelical groups reached out to the settlers of the western frontier. In particular the Baptists and Methodists were skilled at reaching the common man and introduced the concept of “camp meeting revivalism.”(136)

The Cane Ridge Meeting House was the epicenter of the Second Great Awakening in

Kentucky. It lies just 15 miles north of Mount Sterling; the area where William Farrow made his home. The Methodist Peter Cartwright and the Presbyterian James McGready were both instrumental in the use of camp-meetings to reach large numbers of potential converts. More often than not these were loosely organized and typically outdoor meetings in which “fire and brimstone” sermons emphasized to large audiences the urgency of repenting one’s sins and finding personal salvation in Christ. In 1801 the Cane Ridge Revival brought as many as 25,000 people together over the course of several weeks; “thousands heard of the mighty work and came on foot, on horseback, in carriages and wagons; it was not unusual for up to seven preachers to be addressing the crowd at the same time”. More than any other event, this one camp-meeting kindled a religious flame that spread all over Kentucky and the Cumberland.(137)

Peter Cartwright was particularly known for the effect his sermons had on listeners. In his autobiography he describes the emergence of “the jerks” at Cane Ridge, an apparently uncontrollable set of convulsions, coupled with bitter and loud crying, which ended in the converted arising from the spasms to declare his newly found belief in the doctrine of the Lord. In his own words, “No matter whether they were saints or sinners the people were seized with a convulsive jerking all over, which they could not by any possibility avoid. The more they resisted the more they jerked; if they would pray in good earnest, the jerking would usually abate. To obtain relief some would rise up and dance. Some would run, but could not get away. The first jerk or so, you would see their fine bonnets, caps, and combs fly; and so sudden would be the jerking of the head that their long loose hair would crack almost as loud as a wagoner’s whip. They fell into trances and saw visions, and when they came to, they professed to have seen heaven and hell, to have seen God, angels, the devil and the Damned, and under the pretense of Divine inspiration would predict the time of the end of the world, and the ushering in of the great millennium.”(138)

Although no record of Col. William L. Farrow ever being overcome by the jerks exists, his hand-written letters to his son Alexander clearly show a change in his personal religious beliefs over time. His early letters typically ended with the salutation “your father and friend until death”, and there was little talk of spirituality in his pre-1830 letters.(139) However as the years evolved, so did William’s perspective.

In one letter William spoke directly of the Great Awakening, penning to his son Alexander; “You mentioned of a great revival of religion in your section of the country and that Eight of your Children has sought and found the LORD to be a sin pardoning GOD which if rightly attended to is and will be better to them than all of the wealth and riches that this world can bestow. My heart rejoices with yours that your children have in their youthful days turned their attention to religion which qualifies them for time and Eternity. My prayer is that you with your companion and children may continue under the protection of a kind and merciful LORD until he calls you home to spend a happy Eternity with him, and may I be one of that happy number that may join in giving honor glory and praise to JESUS CHRIST my redeemer through the countless ages of Eternity.”(140)

In William’s letters his thoughts often turned to family; the importance of building upon strong family values and passing these on to each new generation. In one letter to Alexander he wrote; “I lack language to express my feelings on the receipt of your letter. It caused me to look back and reflect on past events. I have some consolation in knowing that my precepts and examples had some influence on you, and your conduct has had alike bearing on your children. When I look back and consider the fate of a number of men that commenced on the stage of action at the time you and numbers of them with brighter prospects than you had. Death has overtaken some, others have taken to practices that does degrade human nature while not a few are infidels and worse that, heathens, and now let me say to you that it gives me more consolation to hear of my posterity embracing religion than to hear that they possessed all the honors and riches the world can bestow. Say to my Grand Children as they have received the Lord Jesus so walk in him and the Lord will prosper them, and I hope when the balance of your children comes to the years of maturity that Our God will be their God.”(141)

In another particularly touching letter he wrote; “I was much gratified at the narrative you gave me of your family affairs. Religion is the foundation of happiness in this world and Eternal happiness in the world unto which we are hastening. Industry and sobriety are two of the mainsprings of religion in this life. I hope the LORD will conduct you and your Children in that way that you may find a welcome admittance into the joys of our LORD and SAVIOR Jesus Christ.”(142)

Whether he was moved by the religious revivalism of the times, through the influence of his son Joseph D. Farrow taking up the calling as a Methodist Minister(143), or perhaps just as a maturing man in his late forties looking for more purpose in his life after politics, in 1821 William decided to become a Minister in Methodist Church. At the annual Conference of the church the following year, with William Farrow representing Kentucky in its delegation, it was noted in the minutes that “William Farrow, who was admitted on trial this year and was appointed to the Shelby Circuit with Richard Corwine, but was discontinued at the next Conference, at his own request.(144)

Despite the old adage that business and religion make strange bedfellows, an enhanced sense of community was perhaps only one of the factors in the rising influence of organized religion in people’s lives. One Lexington newspaper noted in their editorial that; “It is well known that a large number of those Christians who belong to the Methodist persuasion also belong to the Masonic fraternity. Their Clergymen especially are among the most zealous supporters of the craft; and it may be added that many respectable Freemasons of this city and vicinity are equally zealous in their attachment to the Methodist Church.(145)

The Whigs Come to Power

The Anti-Masonic political party was in fierce opposition to the presidential politics of the

Democrat Andrew Jackson, ironically himself a Mason. Although the party had only held its first national convention in 1831, it quickly faded into obscurity with many of its former members joining the new Whigs.(146)

Col. William L. Farrow strongly supported the newly formed Whig Party. The Whig party emerged in 1833 primarily from the National Republican party, and made a name for itself by espousing the simple precept that the people were competent to weigh and decide issues of national policy.(147) In their first major test, although William Henry Harrison carried the State of Kentucky in the presidential election of 1836, the Whig party had been split and lost the election to the Democrat Martin Van Buren.(148)

In a March 1838 letter to his son, William laments the current financial problems plaguing the country, “money affairs are very tight with us and if President Van Buren and his party can blind the eyes of a majority of Congress times will certainly be much worse than at present. As you said to me, I hope Congress will do something favourable to our fiscal affairs. Our legislature has passed some very important laws. There is a law calling a convention to reform our constitution agreeable to the mode laid down in that instrument, also a law to have a general school system, with several others not now recollected. I hope when you come to this state you will visit me if I am in being and try and time your affairs to spend a longer space of time with me than you have heretofore.”(149)

In 1839, the Whigs held their first national convention. When the Whigs again ran William Henry Harrison against the incumbent Van Buren in the presidential election of 1840, the county was still stinging from the financial crisis of 1837 and Van Buren had lost much of his popularity.(150) With the Whig party now unified behind Harrison, he won the 1840 presidential election with 52.9% of the vote.(151) Col. William L. Farrow and his eligible descendants, 26 persons in all, cast their votes for William Henry Harrison in that election; a fact of which he was always very proud.(152)

Under the Whigs, the country’s financial situation improved, as it did for William Farrow as well. In one letter he writes; “We had a cold and very dry winter with us, the spring and summer so far has been very favourable. Our crops of small grain and corn at the present is very flattering, the last crop of wheat sold for one dollar per bushel. Corn is now worth 50 cents per bushel. Your brothers Thornton and Nimrod has undertaken to apply steam power to my mill and expects to be in operation by the last of August. They have used all of my works when the water is too low to drive them. How they will succeed is more than I can say. I can say, I have often reflected and lamented the distance that is between our earthly habitations which deprives me of your company. My son let us try to conduct in life that way that we may enjoy Eternal happiness in the world to come in my humble and sincere prayer to the almighty GOD at a stage of my life that I so much need it.”(153)

In another letter, he turned back to politics, commenting on the Whig victory in the gubernatorial race of 1840, “My son Alexander S. Farrow I received your letter dated the 7th of last March from Cincinnati and was much pleased that you was honored as one of the committee to present a young Eagle to that Great and good man General Harrison. Be assured on the receipt of the news that Indiana State was given so respectable a Majority for the Whig cause I was ready to say our prospects was very flattering and when the vote of Kentucky was ascertained to be 15.720 majority for Mr. Letcher, Whig, over Mr. French, Toro, we are still encouraged and every one of us should do his best for the good cause.”(154)

With the Whigs more popular than even, it was Kentucky’s own Henry Clay, who had begun his political career in 1803 as a Representative from Fayette County in the General Assembly of Kentucky,(155) that was nominated as the Whig candidate for president at the national convention in May 1844. He ran against the Democratic Party nominee James Polk of Tennessee, and lost a very close election – a swing of just 20,000 votes out of 2,600,000 would have put Clay in the White House.(156) In retrospect it was Clay’s opposition of the annexation of Texas that cost him the race.(157) William Farrow continued his political support of the Whigs, albeit in later years more indirectly through his politically active children.

Col. Alexander S. Farrow started his political career as a member of the Kentucky General Assembly in 1820(158) and was later active in the drafting of the revised Indiana State Constitution (159), while Kenaz M. Farrow was a member of the Kentucky General Assembly in 1822 (160) and in 1837 went on to become Judge of the 11th Circuit Court.(161) This image of Alexander S. Farrow is believed to be the earliest photograph of a member of the Farrow family; probably taken at the time of the Indiana state constitutional convention of 1850.(162)

Although William Farrow would have been delighted to see the Whigs regain the White

House, he did not live to see the election of Zachary Taylor on the Whig ticket of 1848.(163)

His Master Calls

In his last known letter to his son Alexander, William wrote; “My earnest prayer is that I may be prepared to lay down this body of clay whenever the Master may call for me”.(164)

Colonel William L. Farrow lived another two years before his Master called for him at the age of seventy-five. He passed away on 26 December 1846 at his home in Fleming County, Kentucky.(165)

He was preceded in death by his first wife “Betsy”, Elizabeth Shores Farrow, who died in Fleming County on 5 September 1826.(166) His second wife, Nancy, survived him by fifteen years, passing on 3 August 1861.(167)

William is thought to have died without a will.(168) His son, William L. Farrow Jr., also died in September 1846. An inventory of his son’s estate is recorded in Mason County,(169) and should not be confused with Col. William L. Farrow’s estate.

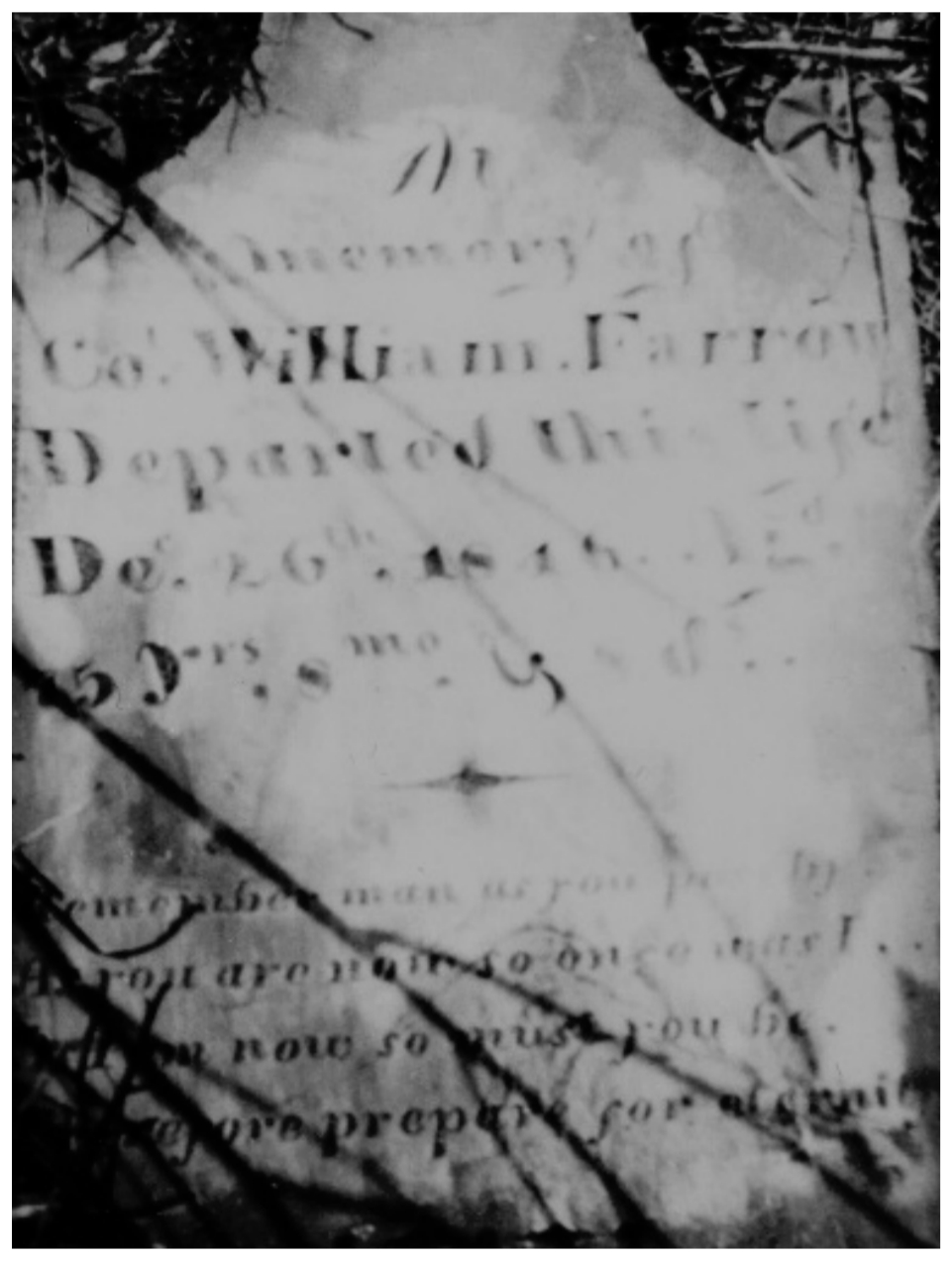

William is buried between his two wives in the Farrow Family Cemetery on the land on which he lived much of his life, near the convergence of Farrow’s Creek and the north fork of the Licking river.(170) His tombstone reads: “In Memory of Col. William Farrow departed this life Dec. 26th, 1846, aged 75 yrs., 8 mos. & 8 days. Remember man as you pass by, as you are now so once was I, as I am now, so must you be, therefore prepare for eternity”.

In his waning years he was almost poetic about death, and wrote to Alexander; “I hope to join them that was so dear to me and you will follow on with your Children. I hope to join that ever-blessed Assembly of Saints and angels to praise GOD through an endless Eternity; that is the humble prayer of your Old Father, Will Farrow Senior.”(171)

Col. William Lycurgus Farrow lived a long and full life. He was a pioneer of Kentucky, helping to shape the state’s future not only as a soldier, but also as a statesman. Many will remember the Farrow family for their exaggerated fondness of lawsuits, but perhaps in retrospect a different and much more important value shines even brighter.

One theme is recurrent in William’s letters, and mirrored from generation to generation in the careful handing down of his words from father to son for more than two hundred years; that of the love of family and traditional values which make our country strong.

Michael M. Wood inherited a group of 18th century family letters in 1987 and has been actively researching, writing and sharing family history ever since. In addition to “Colonel William L. Farrow – Pioneer, Soldier, Statesman”, his published works include the two volume “Legacy, a family history and genealogical record” (2001, copy in the Library of Congress), “Fifteen Generations of the Wood Family” (2008), “Jonathan Wood (1747–1820) of Little Compton, Rhode Island and Dutchess County, New York” (2009, published by NEHGS), “The Farrow Family of Virginia” (2010) and “Stolen Honor – The Land Bounty of Midshipman Thomas Masterson” (2017). Michael currently lives with his wife and two children in Munich, Germany.

Endnotes

-

Paul S. Boyer, “The Enduring vision: a history of the American

people to 1877”, Volume 1, page 202, Houghton Mifflin,

Boston, MA, 1996.

-

Richard H. Collins, “History of Kentucky”, Volume II, Page 637,

published Collins & Co., Covington, KY, 1878.

-

E. Raymond Evans, “Notable Persons in Cherokee History:

Bob Benge”. Journal of Cherokee Studies, Volume 1, Number

2, pages 98-106, published Museum of the Cherokee Indian,

1976.

-

James Pierce, “Frontier Battles of the Revolution”, The Battle

of Blue Licks, Early America Review, Volume III, Number 1,

website earlyamerica.com accessed 15 August 2011,

published DEV Communications, Inc., Bainbridge Island,

Washington, 2000.

-

Richard Peters, “The Public Statutes at Large of the United

States of America”, Volume VII, page 39, Little & Brown,

Boston, 1846.

-

Charles J. Kappler, Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, Volume II

(Treaties), pages 33-34, Government Printing Office,

Washington D.C.,1904, Oklahoma State University Library,

website digital.library.okstate.edu accessed 15 August 2011.

-

General Robertson, “Campaign against Creeks and

Cherokees”, 6 September 1794, Papers of the War

Department, page ID 11679, website wardepartmentpapers.org

accessed 15 August 2011, published Center for History and

New Media, George Mason University, Washington D.C., 2007.

-

Squire M. D. Farrow, letter re-published in the “Daily Evening

Bulletin”, Volume VI, Number 203, page 3, Maysville, Kentucky,

18 July 1887.

-

Edward Albright, “Early History of Middle Tennessee”, Chapter

38, published Brandon Printing Company, Nashville, TN, 1909,

transcription at website rootsweb.ancestry.com/~tnsumner/

early34.htm accessed 15 August 2011.

-

Library of Congress, “A Century of Lawmaking for a New

Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates,

1774-1875”, Washington D.C., 2011, website loc.gov accessed

15 August 2011

-

J. W. Jewitt, “A Portrait of Col. William Farrow of Fleming

County, Kentucky”, handwritten one page document originally

on the reverse of an oil painting of William L. Farrow, written on

8 January 1838, transcription in the collection of the author

Michael Wood.

-

George Henry Townsend, “A manual of dates: a dictionary of

reference to the most important events in the history of

mankind to be found in authentic records”, page 573, published

Warne, London, 1867.

-

Greater Lexington Chamber of Commerce, “History of

Lexington” website commercelexington.com accessed 15

August 2011, Lexington, KY, 2011.

-

William E. Connelley, “History of Kentucky”, Volume 1, page

289, published The American Historical Society, Chicago &

New York, 1922.

-

Michael M. Wood, “Legacy, a family history and genealogical

record of the Wood, Mallory, Miles, Kenney and related

families”, page 605, LCCN: 2001099106, published M. M.

Wood, New York, 2001.

-

Ibid; page 48

-

Dorothy Clark Colwell, “Farrow Family”, page 2, published D.C.

Colwell, Edgewood, KY, July 1989.

-

John H. Gwathmey, “Historical Register of Virginians in the

Revolution”, page 266, published Dietz Press, Richmond, VA,

1938

-

Dorothy Clark Colwell, “Farrow Family”, page 15, published

D.C. Colwell, Edgewood, KY, July 1989.

-

Ibid

-

William Glover Stanard, “Virginia Magazine of History and

Biography”, Volume 29, page 441, published Virginia Historical

Society, Richmond, VA, 1921

-

Dorothy Clark Colwell, “Farrow Family”, pages 17-18,

published D.C. Colwell, Edgewood, KY, July 1989.

-

Joseph M. Farrow, deposition of 6 June 1842, record held in

Circuit Court of Montgomery County Kentucky, as reprinted in

“Farrow Family”, pages 23-25, by Dorothy Clark Colwell, 1989.

-

Michael M. Wood, “Legacy, a family history and genealogical

record of the Wood, Mallory, Miles, Kenney and related

families”, page 27, LCCN: 2001099106A, published M. M.

Wood, New York, 2001.

-

Thomas Farrow and his wife Nancy are mentioned in a 27

October 1832 deed, Fleming County Kentucky Deed Book R,

Page 302, Fleming County Clerk, Flemingsburg, KY.

-

Joseph Farrow’s will, as reprinted in “Legacy, a family history

and genealogical record”, by M.M. Wood, pages 193-194, NY,

2001.

-

Bill Farmer, “Daniel Boone and The History of Fort

Boonesborough”, website fortboonesboroughlivinghistory.org

accessed 15 August 2011, published Fort Boonesborough

Foundation, Richmond, KY, 2011

-

Neal O. Hammon, “Initial Land Acquisition in Kentucky”,

published sos.ky.gov website accessed 15 August 2011,

Secretary of State, Commonwealth of Kentucky, 2011

-

John Frederick Dorman, “Virginia Revolutionary Pension

Applications”, Volumes 11-14, page 74, published J.F. Dorman,

Washington D.C., 1958

-

Governor Edmund Randolph, “Deposition of William Linton”,

Virginia Governor’s Executive Papers, Box 1, Folder 7, Prince

William County Court, Manassas, VA, 3 December 1788

reprinted website pwcvabooks.com accessed 15 August 2011.

-

John H. Gwathmey, “Historical Register of Virginians in the

Revolution”, page 266, published Dietz Press, Richmond,

Virginia, 1938

-

Darren R. Reid, “Daniel Boone and others on the Kentucky

frontier: autobiographies and narratives, 1769-1795”, page 90,

published by McFarland & Co., Jefferson, NC, 2009.

-

Richard Masterson, deposition of 15 June 1797 regarding

preemption in the name of Joseph Farrow, Montgomery

County KY Will Book A, page 263, Montgomery County Clerk,

Mt. Sterling, KY.

-

Michael M. Wood, “Receipts for war services”, “13 March 1776

payment made to Joseph Farrow for waggonage to the troops

of Hampton”, and “A warrant to Joseph Farrow for 22.10.0

pounds for wagon hire to the troops of Hampton”, as reprinted

in “Legacy, a family history and genealogical record”, page

193, by M.M. Wood, NY, 2001.

-

Elaine Walker, “Certificates of Settlement & Preemption

Warrants”, Kentucky Land Office, website sos.ky.gov accessed

15 August 2011, Secretary of State, Commonwealth of

Kentucky, Frankfort, KY, 2011.

-

Richard H. Collins, “History of Kentucky”, Chapter “Fayette

County”, page 177, published Collins & Co., Covington, KY,

1847.

-

Neal O. Hammon, “Initial Land Acquisition in Kentucky”,

website sos.ky.gov accessed 15 August 2011, Secretary of

State, Commonwealth of Kentucky, Frankfort, KY, 2011.

-

Elias Tolin, “Deposition of 27 February 1806” Fayette County

Circuit Court Records, Record Book B, Page 478, reprinted in

“The register of the Kentucky State Historical Society”, Volume

31, pages 237-238, published Kentucky State Historical

Society, Frankfort KY, 1933

-

Patrick Jordan, “Deposition of 5 September 1807”, Fayette

County Circuit Court Records, Book B, Page 467, reprinted in

“The register of the Kentucky State Historical Society”, Volume

31, page 234, published Kentucky State Historical Society,

Frankfort KY, 1933

-

Elias Tolin, “Deposition of 27 February 1806” Fayette County

Circuit Court Records, Record Book B, Page 478, reprinted in

“The register of the Kentucky State Historical Society”, Volume

31, pages 237-238, published Kentucky State Historical

Society, Frankfort KY, 1933

-

Richard Masterson, deposition of 15 June 1797 regarding

preemption in the name of Joseph Farrow, Montgomery

County KY Will Book A, page 263, Montgomery County Clerk,

Mt. Sterling, KY.

-

Neal O. Hammon, “Initial Land Acquisition in Kentucky”,

website sos.ky.gov accessed 15 August 2011, Secretary of

State, Commonwealth of Kentucky, Frankfort, KY, 2011.

-

Josiah Collins, Pension application S30336 of Josiah Collins,

County Court of Bath County, Kentucky, recorded 13 May

1833, Bath County Clerk, Owingsville, KY.

-

Richard H. Collins, “History of Kentucky”, Chapter “Fayette

County”, page 179, published Collins & Co., Covington, KY,

1847.

-

Darren R. Reid, Daniel Boone and others on the Kentucky

frontier: autobiographies and narratives, 1769-1795, Chapter

six, John Shane’s first interview with Josiah Collins, 1841, page

89, published by McFarland & Co., Jefferson, NC, 2009.

-

Richard H. Collins, “History of Kentucky”, Volume II, page 172,

1st lot holders of Lexington, 26 December 1781, published

Collins & Co., Covington, KY, 1847.

-

Elaine Walker, “Land Law 1779 B; an Act for establishing a

Land Office and ascertaining the terms and manner of granting

waste and unappropriated lands”, Kentucky Land Office,

website sos.ky.gov accessed 15 August 2011, Secretary of

State, Commonwealth of Kentucky, Frankfort, KY, 2011.

-

Ibid; Joseph Farrow Warrant Number: 4398.0, 29 March 1780,

Patent 9058.0, 200.00 Pounds & Warrant Number: 4399.0,

March 29, 1780, Patent 3085.0, 200.00 Pounds.

-

Ibid; Joseph Farrow Preemption Warrant number 865.

-

Ibid; Joseph Farrow Warrant Number: 15426.0, 10 April 1783,

4348.00 Pounds.

-

William E. Connelley, “History of Kentucky”, Volume 1, page

289, published The American Historical Society, Chicago &

New York, 1922.

-

John Bradford, “Kentucky Gazette” newspaper, 3 January

1789, page 1, Lexington, KY, 1789.

-

Virginia Council of State, “Journals of the Council of the State

of Virginia”, Volume 5, page 119, Virginia Division of Purchase

and Printing, Richmond, VA, 1982

-

Willard Rouse Jillson, “The Kentucky Land Grants”, (Records

of the Kentucky Land Office, Book 14, Page 507), Volume 1,

Part 1, page 48, Filson Club Publications, Louisville KY, 1925

-

Joseph M. Farrow, deposition of 6 June 1842, record held in

Circuit Court of Montgomery County Kentucky, as reprinted in

“Farrow Family”, pages 23-25, by Dorothy Clark Colwell, 1989.

-

First Census of the United States, Records of the Bureau of

the Census, 1790, Microfilm publication M637, National

Archives, Washington, D.C.

-

Commonwealth of Kentucky, “Early History of Kentucky”, KY

State website Kentucky.gov accessed 15 August 2011,

Commonwealth of Kentucky, Frankfort, 2011.

-

Joseph M. Farrow, deposition of 6 June 1842, record held in

Circuit Court of Montgomery County Kentucky, as reprinted in

“Farrow Family”, pages 23-25, by Dorothy Clark Colwell, 1989.

-

Ibid

-

William Farrow letter of 20 September 1840, “Give my sincere

respects to my Old and faithful friend Joseph Frakes for he has

been my friend in need and deed”, reprinted in “Legacy”, pages

211-213, by M. M. Wood, New York, 2001.

-

John Bradford, “Kentucky Gazette” newspaper, 15 March

1797, page 1, Lexington, KY, 1797.

-

A. Goff Bedford, “Land of our Fathers: History of Clark County,

Kentucky”, “Clark County Tax Roll”, publisher: A.G. Bedford,

Mt. Sterling, KY, 1958, reprinted Clark County GenWeb,

website kykinfolk.com accessed 15 August 2011.

-

Michael M. Wood, “Legacy, a family history and genealogical

record of the Wood, Mallory, Miles, Kenney and related

families”, Volume 1, page 202, Farrow family letters, LCCN:

2001099106, published M. M. Wood, New York, 2001.

-

Lula Reed Boss, “Fleming County, Kentucky”, Kentucky

Ancestors, Volume 7, Number 2, page 68, Kentucky Historical

Society, Frankfort, KY, October 1971

-

Michael M. Wood, “Legacy, a family history and genealogical

record of the Wood, Mallory, Miles, Kenney and related