By: Louise Jones, KHS Director of Research Experience

Editor’s Note: The following report comes to us through the research that was conducted for the first Kentucky Ancestors Town Hall event in 2017.

As we get deeper into our family histories, it is not uncommon to find an ancestor or related family that experienced some part of the great American westward expansion. Perhaps your family only skipped a few states over and settled midway across the country, or perhaps you have tracked them from the east to west coast and back again. For many family historians the work is in the laborious process of weeding through census, land and tax records to rebuild the story of exactly when, why and where ones antecedents went. With the majority of our energy focused on this, it is not surprising to know that most of us do not spend too much time thinking about the “how.”

Last summer, as part of our research into one of the applications to Kentucky Ancestors Town Hall 2017, we uncovered the remarkable story of the Boyer family of Hickman, Kentucky. John Boyer operated a ferry across the mighty Mississippi River that ran from just south of the town of Hickman over to Dorena, Missouri.[i] Dorena was not really much more than a landing place and link to routes across Missouri, but Hickman during this time was a town with merchants, manufacturing and plenty of resources.[ii] It was an attractive place for those settlers looking for a way west but who also wanted realistic advice on what they needed to survive the trek.

John Boyer appears to have established the ferry in about 1842 and run it until his death in 1873.[iii] By looking through court records and newspaper articles, we can begin to understand just what the business of ferrying people and goods across the Mississippi involved. Boyer had to appear in court periodically to renew his ferry license and to renegotiate the fees he could charge for people, wagons, horses and other livestock. Advertising in local newspapers allowed Boyer to use images as well as words to let travelers know about his ferry, especially since he was not “in town.”[iv] The ferry was also not his only source of income, as the 1850 and 1860 Census both show his occupation as farmer. The ferry was probably a lucrative way to supplement his farm income.

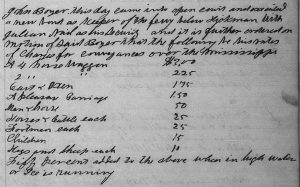

The annals of history will find their way into every family story: Hickman was one of many communities along the Mississippi that frequently changed hands between the Confederate and Union troops during the Civil War. As early as 1861, Union officers were reporting that Hickman was in Confederate hands.[v] We know that John Boyer lost his ferry to a Union sweep in 1863, done in an effort to cut down on Confederate activities on the river. On 30 July 1863, Boyer requests the return of his ferry but does not receive a reply.[vi] However, as soon as the war is over, Boyer is back in business, as can be seen from this Internal Revenue tax document.[vii]

In the case of the Boyer ferry, John Boyer owned land on both sides of the river, which probably facilitated his ability to ensure smooth landings on both sides. John Boyer died in 1873. However, his will divided the property between the children of his first marriage (adults in 1873) and the heirs from his second (minors in 1873)[viii]. Family dynamics being what they were, as well as the age of the heirs, created a break in the “family owned” business and the ferry right was turned over to outside managers and eventually sold[ix].

The completion of the transcontinental railroad system between 1869 and 1880 may very well have led to the demise of small, family owned ferry rights all along the Mississippi. Once settlers had safe, reliable and efficient means of reaching the far western territories, overland travel by wagon would become far less attractive to settlers. By the turn of the century, ferries like the one at Hickman would be used primarily for local traffic back and forth across the river.

The Boyer ferry is both an interesting glimpse into the experience Americans had as they moved westward toward the open expanses of the far west and an amazing family legacy. Many family historians learn of their ancestor’s occupations or businesses through federal records (like the Census) or personal records (like obituaries). These clues can bring a deeper appreciation for the roles our family members played in history.

About the author:

About the author: Louise Jones is in charge of connecting the dots. As leader of the Research Experience team, it is her responsibility to help connect researchers to the collections and resources they need, whether that is through the Martin F. Schmidt Research Library, the pages of The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society or the Civil War Governors of Kentucky, Digital Documentary Edition. Louise brings to her work a broad range of experiences in making collections accessible to the public through research services, programs, community events and online publications. One highlight of her career while working at KHS has been helping to index the 1940 Census, where she actually got to index the page showing her great, great grandmother. She holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in history, Master of Library Science degree and attended Developing History Leaders @SHA.

[i] Fulton County, Kentucky. Order book, 1855, p. 485.

[ii] Plan of the City of Hickman and Vicinity, Fulton County, Kentucky, 1857.

[iii] Fulton County, Kentucky. Order books, 1855 (p. 485), 1865 (p. 562), 1869 (p. 229), 1874 (p. 473, 501).

[iv] “Boyer Ferry,” Hickman Courier (Kentucky), 28 Feb 1874, p. 3, digital image, Newspapers.com (http://newspapers.com ); accessed 6 April 2017.

[v] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series I, volume 22, p. 309.

[vi] Union Provost Marshals’ File Of Paper Relating To Individual Civilians, 1861-1867, John Boyer to Brigadier General Asboth, 30 July 1863, digital image, Fold3.com (http://fold3.com ); accessed 6 April 2017.

[vii] United States. IRS Tax Assessment Lists, 1862-1918, John Boyer, December 1866, digital image, Ancestry.com (http://ancestry.com ); accessed 6 April 1917.

[viii] Fulton County, Kentucky. Will book, 1873, p. 133.

[ix] Fulton County, Kentucky. Order book 3, 1874. P. 501, Order book 3, 1875, p. 583, Order book 6, 1892, p. 94, 105 and 106.