By: Bill Burchfield, MSLS, Kentucky Historical Society Librarian

We all know that the early history of the United States is filled with disease epidemics. Kentucky has shared in their sometimes-disastrous outcomes. Cholera was an especially dreadful disease that cropped up from time to time in various locations throughout the Commonwealth in the mid-19th century. Many times, cholera would break out more than once in a location given it is caused by contaminated water. Water purification and sanitation were wholly different in the 19th century compared to today, plus, methods to prevent contamination were not fully understood.

We all know that the early history of the United States is filled with disease epidemics. Kentucky has shared in their sometimes-disastrous outcomes. Cholera was an especially dreadful disease that cropped up from time to time in various locations throughout the Commonwealth in the mid-19th century. Many times, cholera would break out more than once in a location given it is caused by contaminated water. Water purification and sanitation were wholly different in the 19th century compared to today, plus, methods to prevent contamination were not fully understood.

Yellow fever was another powerful disease that brought sorrow and death to the United States and Kentucky. This disease provides another example of how poor knowledge of infectious diseases and how they spread often led to tragedy. Though it was mainly known as a tropical disease, commerce and travel up and down the Mississippi furthered its reach into Kentucky. One such arrival hit the western portion of the state with deadly devastation in 1878. The southern United States was so ravaged by the outbreak, that refugees from the southern catastrophes brought the disease, which was then spread further by our prolific mosquito population.

Though the effects of these epidemics, and their wrath were horrifying, many physicians and medical professionals, recognized the importance of documenting the progression and treatment of the diseases in their locality for research purposes. They didn’t fully understand what was happening to the people around them or how to treat them, but they knew that documentation could lead to a breakthrough in understanding. Because of their forward thinking and through modern digitization, we can take advantage of this documentation for a different purpose than originally intended: genealogy.

Most people would not think of using a medical library to do genealogy research but when you are looking for one last elusive nugget that makes it all come together you start to expand your definition of a normal resource to ensure a reasonably exhaustive search. The National Library of Medicine has a thriving digitization department. They have several overhead scanners in the stacks area. The separate digital processing area is an amazing site to see, and the team they have doing the scanning and processing is a wonderful group of talented individuals. This all comes together in a digitization program that would be a challenge to surpass and they are constantly providing access to new works online virtually every day.

Most people would not think of using a medical library to do genealogy research but when you are looking for one last elusive nugget that makes it all come together you start to expand your definition of a normal resource to ensure a reasonably exhaustive search. The National Library of Medicine has a thriving digitization department. They have several overhead scanners in the stacks area. The separate digital processing area is an amazing site to see, and the team they have doing the scanning and processing is a wonderful group of talented individuals. This all comes together in a digitization program that would be a challenge to surpass and they are constantly providing access to new works online virtually every day.

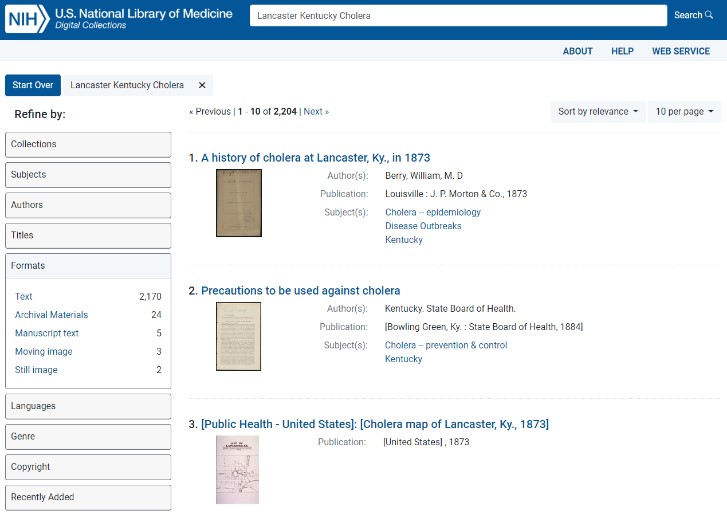

To get started using the National Library of Medicine Digital Collections simply point your browser to https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/. On this page you will find the main search box for the digital collections catalog. You do not need to sign up for anything. No username or password needed. Just head there and start searching. The search engine works much like any other online catalog you may have used to search the stacks of your local library holdings.

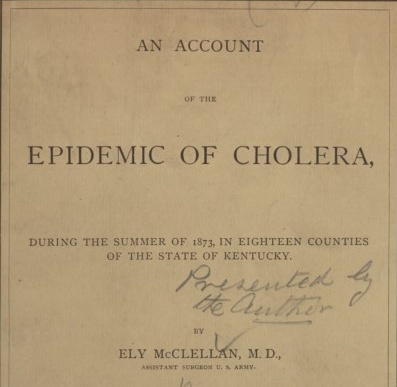

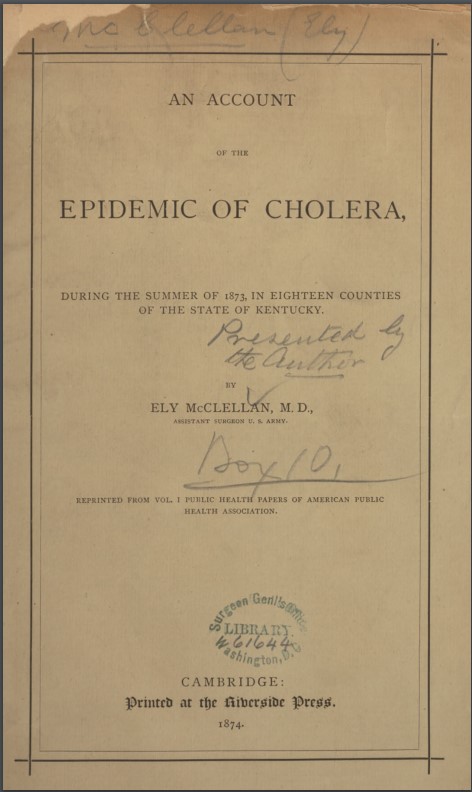

One excellent search you can use is a location and cholera (e.g. Lancaster Kentucky Cholera). With this search, one of the first items returned is A History of Cholera at Lancaster, KY., in 1873. This little book provides a wonderful account of the epidemic of 1873 written by two doctors. At the beginning of the book, there is a map that indicates the location of each case of cholera in Lancaster. It gives a great accounting of how quickly people could become infected, their trials as the illness ran its course, and whether they survived their ordeal. The most exciting part, at least from a genealogical viewpoint and the real reason we are here, is that this was before the time of medical privacy, so the individuals are actually named. This can be a boon for someone up against a “brick wall” trying to figure out what happened to their ancestor.

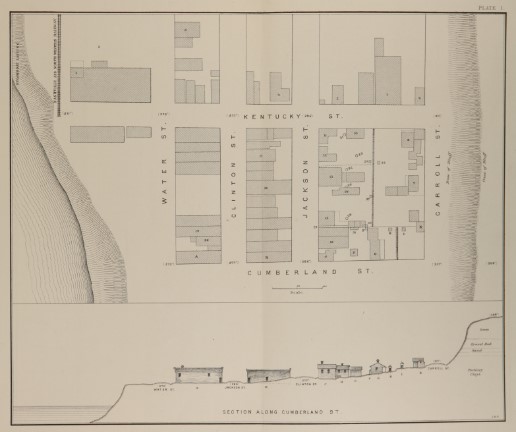

Another fine example would be a location and yellow fever (e.g. Hickman Kentucky Yellow Fever). A title close to the top on this search is Notes on the Yellow Fever Epidemic at Hickman, Ky., During the Summer and Autumn of 1878. This book starts with a description of the area, which is quite detailed, including soil analysis, due to its producer, the Geological Survey. There are many details that can help researchers analyze the town including town maps and elevation sketches similar to our other example. These can be useful to gain a feel for the area even if we do not see our ancestor named.

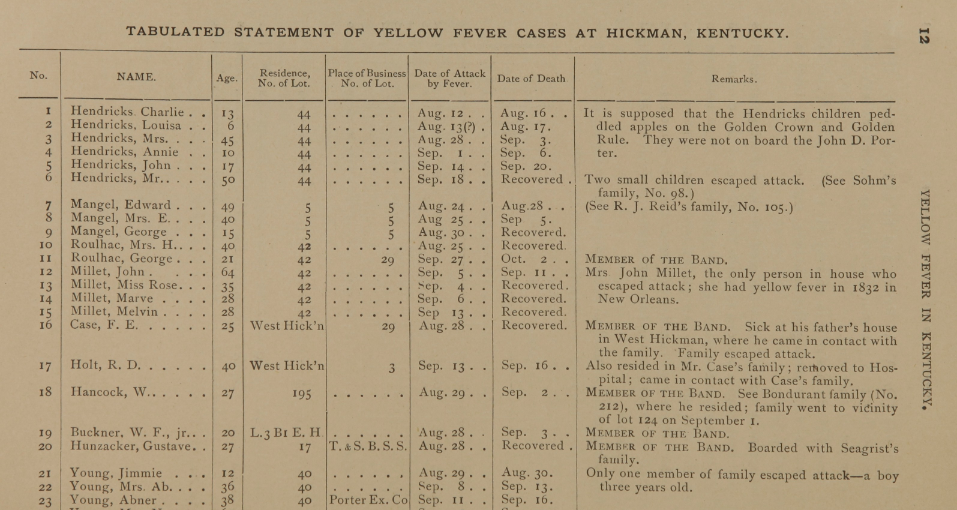

After the geologic description comes a very detailed reporting of the events leading up to and during the epidemic. In this account, the victims of the epidemic are named in a table with detailed demographic information, the date they became ill, and their date of death or a note that they recovered. Some of the entries contain other remarks that could contain valuable research information – such as occupation, residence, and movement during the epidemic. Be careful: Notice that the entries (below) at first appear to be in alphabetical order – but they are not – the names are listed in victim order. This may mean quite a bit of scrolling through each page, but there aren’t too many, and the supplemental details included are worth the extra effort!

Sadly, not all locations had physicians or others in a position that could take the time to write papers on the experience. Another problem you may run into is that even though privacy laws were vastly different back then, some writers still only used initials to keep names confidential. Considering that there were many different kinds of disease outbreaks that could cause widespread problems, try searches for many different diseases such as smallpox, typhus, measles, or influenza as a few examples. Also, do not limit your search to simply the location you believe your ancestor was located, try some surrounding ones. You can even try state level searching (e.g. Kentucky Cholera or Kentucky Yellow Fever). You will have more items to filter through, but it can be an effective way to find a resource if you are not having luck with the smaller locations you try. Using this research method may seem a bit strange at first but will soon feel like reading any other book in hopes of finding a nugget of information to break through a “brick wall.”

About the Author:

Bill Burchfield, MSLS, is a Librarian for the Martin F. Schmidt Research Library at the Kentucky Historical Society. He holds a Bachelor of Arts in Organizational Leadership from Northern Kentucky University and a Master of Science in Library Science from the University of Kentucky. Bill is a member of the Kentucky Library Association and the American Library Association. He has written and lectured on research and information seeking and his academic research work has seen international attention. Bill also interned at the National Library of Medicine while completing his MSLS degree.

Bill Burchfield, MSLS, is a Librarian for the Martin F. Schmidt Research Library at the Kentucky Historical Society. He holds a Bachelor of Arts in Organizational Leadership from Northern Kentucky University and a Master of Science in Library Science from the University of Kentucky. Bill is a member of the Kentucky Library Association and the American Library Association. He has written and lectured on research and information seeking and his academic research work has seen international attention. Bill also interned at the National Library of Medicine while completing his MSLS degree.

References:

Berry, W., & Wilson, F.C. (1873). A History of Cholera at Lancaster, KY., in 1873. Louisville, KY: John P. Morton & Company.

Marvin, J.B. (1878). A History of the Diagnosis, Pathology, and Treatment of Yellow Fever. Louisville, KY.

McClellan, E. (1874). An Account of the Epidemic of Cholera During the Summer of 1873, in Eighteen Counties of the State of Kentucky. Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press.

McClellan, E. (1874). Cholera Hygiene. Louisville, KY: John P. Morton & Company.

National Library of Medicine (n.d.). Home page. Retrieved April 3, 2020 from https://www.nlm.nih.gov/

National Library of Medicine (n.d.). Digital Collections. Retrieved April 3, 2020 from https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/

Procter, J.R. (1879). Notes on the Yellow Fever Epidemic at Hickman, Ky., During the Summer and Autumn of 1878. Frankfort, KY: E.H. Porter.