By Your Kentucky Ancestors Team

So you’ve seen the ads on TV for Ancestry.com, and begun to wonder “Can it really be that easy?”

Why yes, it can. It can also be a bit more complex, if you want more than can fit into a 50 second video clip. This article is aimed specifically at people who are ready to begin the initial stage of their own genealogy research. It includes suggestions designed to help you get started and to make the most productive use of your time and the genealogical materials you find as you do your family history research.

Start With Yourself

Many people ask the basic question: “How do I start doing my family history?” The answer should always be to begin with the things about your personal life and family history that you know. Document the things you already know and then begin to research and discover the family history you do not know. Write down your own vital statistics: when and where you were born, where you went to school, the jobs you have held during your life, and other significant events that you know for sure. Then, do the same thing with the next generation—your parents. You can start with something as simple as a blank sheet of lined paper. Use one for each person. Write down the name of your father on one sheet and your mother on another, and begin to document as many pieces of information about each of their lives that you can. Here are some of the items that you want to gather about your parents and then earlier generations as you begin to move back through your own family history:

- Birth date and place

- Parents’ names

- Marriage date and place

- Death date/burial site/cause of death (if known)

- Education (name of school, place)

- Occupation (name of company, address)

- Military service (service dates, places)

- Significant life events (won their entry in the state fair, took part in a peace rally at the state capitol)

You will notice that events are often paired with the words “place” and “date.” Knowing where and when something occurred will make it easier to track down records documenting that event.

Gather Documentation

We live in an age where every life event from kindergarten graduation to marriage vow renewals comes with its own set of documents proving that this happened, even if it is only family photographs. As you go back in time, documentation becomes less standardized and far less voluminous. As you start building your family tree you will begin to find documents that verify and add information to your knowledge of each event. For example, a birth certificate may tell you how much the baby weighed and what time of day the birth occurred, things that may have passed out of the memories of those involved. Gather the details (births, marriages, deaths, education, etc.) and the documents that back up the dates and places of those events as often as possible.

As you begin to get beyond the simple list of child, parents and grandparents, you will find that you may need to organize your findings in a notebook or file system. Your system will keep your documents organized and readily available as you need to refer to them. Unless you have a photographic memory, you will want to acquire copies of some documents, because you will go back to some records over and over. Good examples of this are records of the U. S. Census. As you get into earlier generations where your ancestors are listed on U. S. census records, get an actual printed copy of the census schedule that contains your ancestors. There are a number of items of important and useful family history information that can be found on the most recent censuses and even earlier ones.

- Family and household organization – names and ages of all living in the house at the time including boarders, in -laws, etc.

- Occupations of those listed

- Birth state of the various members of the family and of their parents

- Level of school completed

- Neighbors (the other people listed on that page of the schedule or the ones before and after it)

As you get further into your research you may find yourself going back to certain Census sheets to verify a bit of information or to compare two bit of conflicting data. You may also find that the unrelated boarder in one census becomes your great uncle in another.

Going forwards and backwards

As you begin your family history research, you may find it easy to find information on your own generation and more recent generations. As you go back in time you may try to research in a “straight line”: you, your parents, grandparents, great-grandparents. If you are interested, you can also branch out to list your parents’ siblings and your grandparents’ siblings. In some cases you may need to research those branch families in order to fully document each person. There are forms that can help you keep it all straight.

An Ancestor Chart is a form that documents a “straight line” by showing child to parent to parent and allows you to put in basic information about birth, marriage and death. A Family Group sheet documents all information about a couple and the children linked to them (birth or adoption). Both forms represent different ways of looking at family. Using these forms lets you organize your findings and to see gaps in information that you still need to fill. When you find out each fact about one of your ancestors, take the time and effort to write a complete description of the document and research site where you found that information. You will find this saves time in the end and keeps you from getting frustrated. We all wish we had photographic memories but very few of us do.

If you decide to research backwards (child, parent, grandparent) as well as forwards (child, parents and their siblings, grandparents and their siblings, etc.) you will definitely want to find an organization system that works for you. The more generations you add to your research, the more complex your tree will get. Do not be overwhelmed by the prospect of doing this amount of in-depth research. You will be amazed at how interesting it will be to find as much information as possible about each of your ancestors as you go through your research.

Where and When: place names and dates

One important fact that you must determine about any person you are researching is what state and county they lived in; where they were born, married, died, and were buried. You need that information for every place they were located during their life, but knowing the state and county is vital to focusing your research efforts most effectively and ensuring the highest degree of success in finding the genealogical information you need. If you do not know the specific county an ancestor lived in, even a close estimate of possible counties will help you to narrow your search.

It is also important to understand that where a town is in 2013 may not be where it was in 1792. State lines, county lines and event town names change over time, and one way to keep track is to seek out a book or website on county boundaries for each state you search for records in. Gazetteers and other geographical reference works can help with name changes and also with a bit of information on the formation and settlement of places.

Information Sources for Family Historians

One of the most confusing aspects of researching your family tree can be the sheer wealth of information sources available. Here is a brief list of the types of documentation you may use in compiling a family tree:

Published Sources

- Family Histories (published and unpublished)

- County Histories (and other county level indexes, abstracts, etc.)

- City directories

Public Records (issued by a government office)

- Birth records

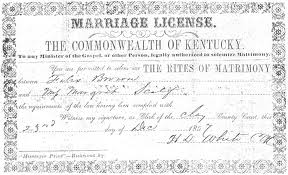

- Marriage records

- Death records

- Military discharge papers

- Immigration and naturalization records

- Census schedules

- School censuses

- Tax lists

- Probate records including will and estate records

- Deeds and other land records

- Court records documenting property disputes, criminal prosecution and other legal actions

- Adoption records

Non-public records

- Family letters, diaries, bible records and family photographs

- Oral history information—interviews with parents, grandparents, aunts/uncles, and other relatives

- Complied genealogical data (research materials compiled by another genealogist

- Fraternal organizations and other social or occupational membership organizations

- Employment records

- Cemetery records or documentation including tombstone information, cemetery register and grave information

- Education records including graduation certificates and yearbooks

- Funeral home records

- Church records (baptism, attendance, marriage, burial)

Oh, the places you will go

As you progress with your research beyond those family members in your immediate reach you may need to go further afield to answers to all your questions. Beginners may find it more helpful to start at a library or historical society that serves large numbers of family historians. The staff at these places will be very experienced with answering questions about where to start. You may also find useful resources at your local public library or at the courthouse in the county where your family lived for a period of time. In addition to libraries, archives and courthouses, you may find cemetery research rewarding. There is a tremendous wealth of information available at the graves of your ancestors.

Using death records, church records and obituaries, locate the place where your ancestors are buried and make a research trip. Grave markers can be a treasure trove with names, date of birth, date of death, military service, name of spouse or parents. If you know the name of the cemetery and the location where your ancestors are buried, you may be able to research much of the information even if it is not possible for you to make the necessary trip to actually go to the site. You may want to search the catalog of the library closest to the cemetery to see if they have a local index to that burial place. And the state historical society or state library may also have resources on cemetery burials. Also, take your digital camera, extra memory cards, and batteries with you to photographically document your ancestors’ gravestones and their location in the cemetery.

Online Genealogy Information

Yes, we know this is where most people start and many stop their search for ancestral information. You will find an overwhelming amount of information online on sites like Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org. All of this information can be used to piece together your family story but some of it may lead you to wonder whether your time may be better spent playing golf. It is best to approach any online session with a task list: “Today I will look for all the information I can find on Grandmother Shelby in the Census.” If you do not want to pay for access to Ancestry.com or HeritageQuest, check with your local library to see if they have subscriptions. You can also search sites like FamilySearch.org for free and gain access to rich databases filled with digital images of documents from all over the country. You do not have to travel to California or Colorado to access public and private records held there.

Things you may want to bear in mind

As you start your genealogy research, there are some basic cautions that you should be aware of and consider in advance that may keep you from making serious mistakes as you undertake your research. Anyone who has done their family history research in the past would probably tell you that they wish they had known these possible problem areas before they ever began.

1. Be skeptical of every document you find. The degree of accuracy in information you find in your research is always suspect. The potential problems you will find in census schedules, birth and death certificates, etc., are so many that they would require another article to address. Just be careful as you document vital statistics and make sure you document the source of any piece of information that you write down. There is nothing more frustrating than looking at a date or place later in your research with a degree of certainty that it is probably incorrect and not being able to easily determine where you initially found that erroneous fact.

2. Do not assume that a person found in your research is THE ancestor you are searching for because the name, date of birth, and age seem to be just what you would expect. It is not unusual to find more than one person in your genealogy research that has the exact birth year and name that would fit the spot you are seeking to fill in your family tree. That can certainly be true for a person with a common surname, but it can also be true for people who had what you might consider unique surnames or even first names.

3. Do not copy information from someone else’s family tree into yours without also copying the supporting documentation. It is possible to find complete multi-generation family histories online and at your local genealogical society that have what appears to be all the names you are seeking. The information may be accurate and have all the correct people, but it may also be full of all kinds of errors and you have no way of knowing that unless the family tree is also documented with all of the associated references that substantiate the material as being correct.

4. Establish an organization and filing system to keep your family history information. You will be amazed at the quantity of paper and notes you will accumulate if you invest any amount of time in your family history research. Before you make that first online genealogy search or open the first genealogy reference book, you should have some folders ready to corral the paper and documents you will begin to gather.

5. Look for help from the experts or other researchers. Check out your local genealogical society or public library offerings. Do they have “Beginner” help sessions periodically? Do they offer workshops? The Kentucky Historical Society has an array of workshops, small group instruction, and sharing sessions that bring beginners into contact with experts from all walks of life. Our Second Saturday workshops are free of charge (unless you choose to reserve a lunch), and the sessions cover a wide variety of topics each year.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Carmack, Sharon DeBartolo. Organizing Your Family History Search: Efficient & Effective Ways to Gather and Protect Your Genealogical Research. Cincinnati: Betterway Books, 1999.

Croom, Emily Anne. The Sleuth Book for Genealogists: Strategists for More Successful Family History Research. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2008.

Croom, Emily Anne. Unpuzzling Your Past: A Basic Guide to Genealogy. 3d Ed. Cincinnati: Betterway Books, 1995.

Frisch, Karen. Creating Junior Genealogists: Tips and Activities for Family History Fun. Provo, UT: Ancestry, 2003.

Hogan, Roseann R. Kentucky Ancestry: A Guide to Genealogical and Historical Research. Salt Lake City: Ancestry, 1992.

Mills, Elizabeth S. Evidence: Citation & Analysis for the Family Historian. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1997.

Mills, Elizabeth S. Evidence Explained: Citing History Sources from Artifacts to Cyberspace. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2007.

Schweitzer, George K. Kentucky Genealogical Research. Knoxville: 1995.

free sample just need to mind that the that nothing wish alter.

Hello,

I just want to say THANK YOU for all the information you have written, compiled, and offered on your website! I cannot imagine the time and effort it has taken to put together such a diverse and helpful set of info.

Sincerely,

Carey Killian