By: Patrick A. Lewis, Ph.D., Project Director, Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition

The Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition digitally publishes the papers of Kentucky’s five wartime governors, but don’t let the name fool you. This isn’t a project about the governors; it’s a project that works through them to glimpse the lives of countless Kentuckians and their communities. Civil War Governors publishes military correspondence, political speeches, court documents, and thousands of letters and petitions from every corner of the Commonwealth. It collects the voices of everyday people whose world is being torn apart by violence and war—not on some far off battlefield but in their neighborhoods.

How can family and local historians find new branches of the family tree and explore hidden local stories through Civil War Governors? Let’s look at a test case.

Growing up in Trigg County, I was steeped in Civil War history. We remembered the Civil War, we “felt” the Civil War, but I can’t say I knew much beyond the broadest strokes about how it affected the lives of people living in the county at the time. There were plenty of legends and stories, but the one that always caught my imagination was one about the naming of the town of Golden Pond.

Golden Pond is, itself, now a legend. A hundred years after the Civil War, the town and the third of the county laying between Barkley and Kentucky Lakes was—controversially—abandoned and turned over to the federal government. The area is still operated as Land Between the Lakes National Recreation Area.

But among many stories about the naming of the town that involved moonshiners, the glinting of the sun’s rays, and bullion rich ’49ers, my favorite was the one about lost Confederate gold. At the end of the war, Confederate cavalrymen were being pursued into Tennessee by some dogged Yankee horsemen. Under fire and needing to make the Tennessee line, the rebels dumped the contents of their wagons, including chests of gold robbed from a northern bank, in a nearby pond. Hence, Golden Pond. On school trips to LBL, I would tell this story to my classmates and we would stare into the depths of every body of water we came across, hoping to strike it rich.

Plug “Golden Pond” into the search box on the new Civil War Governors site, and we get one clean hit. Our long-lost treasure map? Not quite, but still interesting. In May 1864, Robert V. Grinter wrote to Governor Thomas E. Bramlette about the situation in Trigg. Turns out Golden Pond is already established and named—so much for the legend of rebel gold. But somebody had clearly been stealing something. “I am compelled to write to you for if Something isn’t done the People will be entirely broken up—we hear evry day the Stealing of Horses by Guerrillas Stores broken open & Pilliaged and plundered by these theiving bands.” Grinter, who signed himself as a veteran of the 8th Kentucky Cavalry (U. S. A.), begged permission to raise a group of home defense soldiers to protect the Unionists “between the Rivers”.

Plug “Golden Pond” into the search box on the new Civil War Governors site, and we get one clean hit. Our long-lost treasure map? Not quite, but still interesting. In May 1864, Robert V. Grinter wrote to Governor Thomas E. Bramlette about the situation in Trigg. Turns out Golden Pond is already established and named—so much for the legend of rebel gold. But somebody had clearly been stealing something. “I am compelled to write to you for if Something isn’t done the People will be entirely broken up—we hear evry day the Stealing of Horses by Guerrillas Stores broken open & Pilliaged and plundered by these theiving bands.” Grinter, who signed himself as a veteran of the 8th Kentucky Cavalry (U. S. A.), begged permission to raise a group of home defense soldiers to protect the Unionists “between the Rivers”.

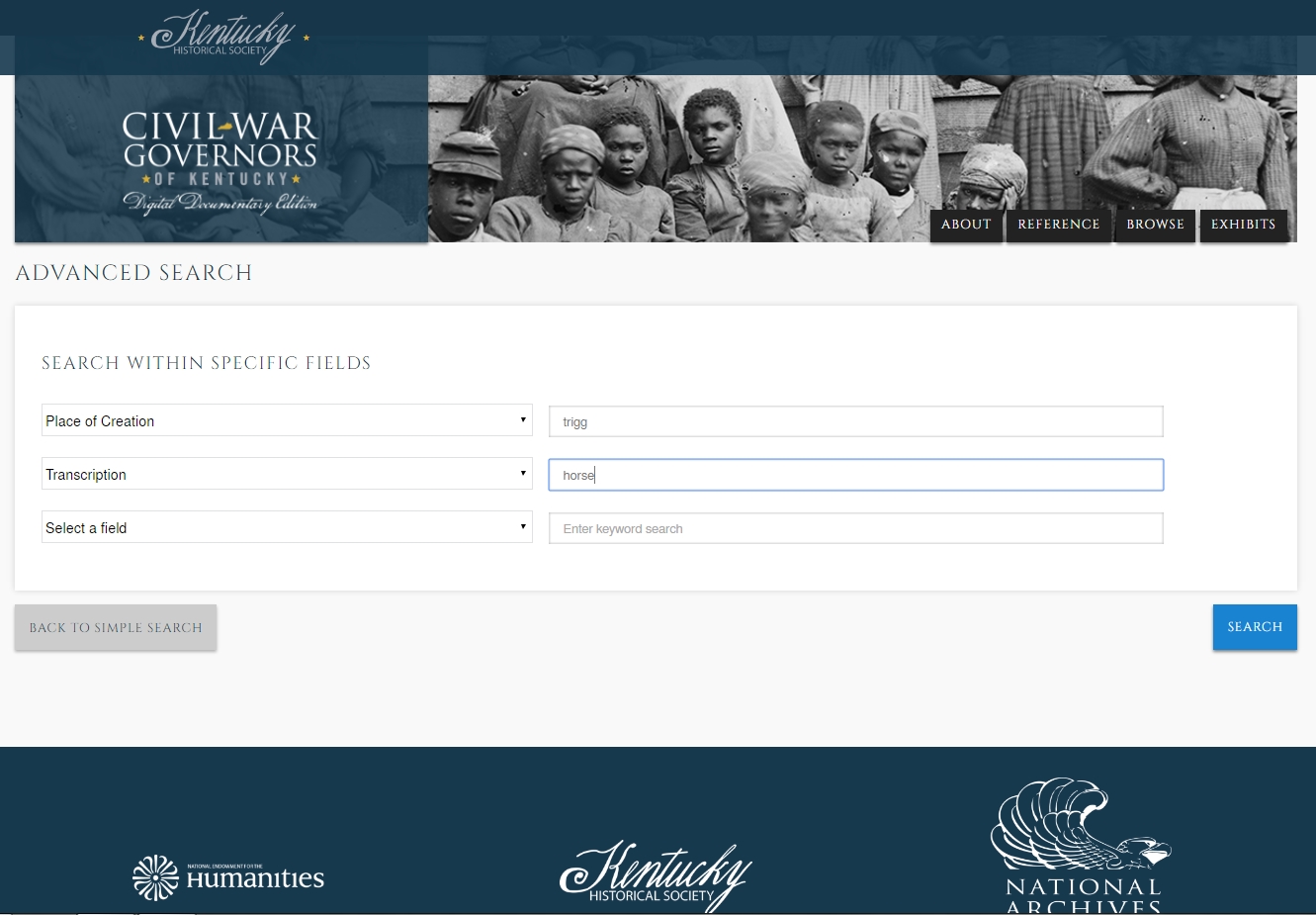

How bad was the horse theft problem in Trigg? I flipped over to the advanced search page, listed place of creation as Trigg and searched those transcriptions for “horse.” My results pulled Grinter’s letter, an indictment against one Lofton Mitchell for horse stealing and, more intriguingly, a petition to Governor Bramlette asking to have that same indictment and conviction overturned.

“We Know Mitchell to have been an ardent and active Union Man,” a number of petitioning neighbors informed the Governor, and that after active service in the 8th Kentucky Cavalry under Robert Grinter, Mitchell “was honorably discharged after having made a gallant and active and enterprising soldier”. Echoing the story that Grinter had told Bramlette months before, “after the Regt was mustered out of service, [Mitchell] and a number of his neighbors united for the purpose of protection from Guerilla Bands prowling about and who were particularly vindictive and cruel towards all who had been in the Federal service.”

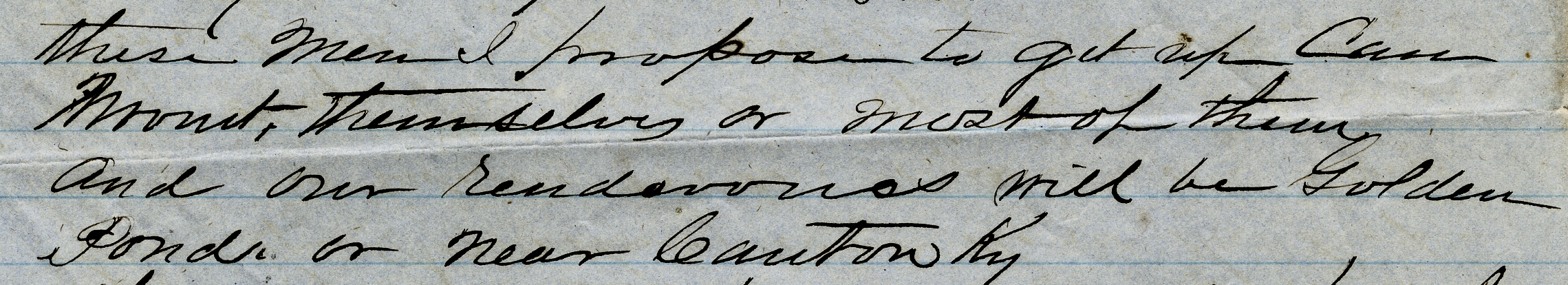

And then the origins of the Golden Pond legend became crystal clear. While Mitchell and his local unionist militia were active, a Rebel Col. or Major named Bob Martin made ^a raid^ into the Counties of Trigg, Christian, Muhlenburg and Caldwell counties, and were pursued by the forces of the 3rd Ky Cavalry, Col Murray and driven again across Cumberland river and on their retreat encamped between Cumberland and Tennessee on his return loaded with booty. These Home guards got together and prominent among those were Lofton Mitchell pursued Martin and attacked him in Camp and routed him and […] near all his booty arms &c They returned the horses taken from neighbours and turned over the other possessions to Col [E]. H. Murray at Hopkinsville.

Mitchell later reenlisted in a state cavalry regiment and was accused of stealing horses from local rebels when he was under orders from a U.S. commander to impress them into federal service. Whatever the legality of the government’s confiscation policy, Mitchell’s neighbors argued, he should not be held personally responsible in a suit they claimed was political retaliation against Trigg County’s unionist minority.

At the September 1865 term of the Trigg Circuit Court, “the Grand Jury composed almost wholly of rebels have indicted said Michell for Robbery in taking and riding the horse under the above circumstances. We know the petit Juries to be composed nearly altogether of Rebels and Believe if the case comes to trial they will if permitted by the court find him guilty.” Such charges leveled against both sides were not uncommon as the shooting war slowly simmered down to peace. In fact, unionist courts in neighboring Caldwell had indicted rebel soldiers on precisely the same charges, and the General Assembly had to step in with 1867 legislation that forbade the criminal prosecution of soldiers on either side for wartime acts that fell within the bounds of just war.

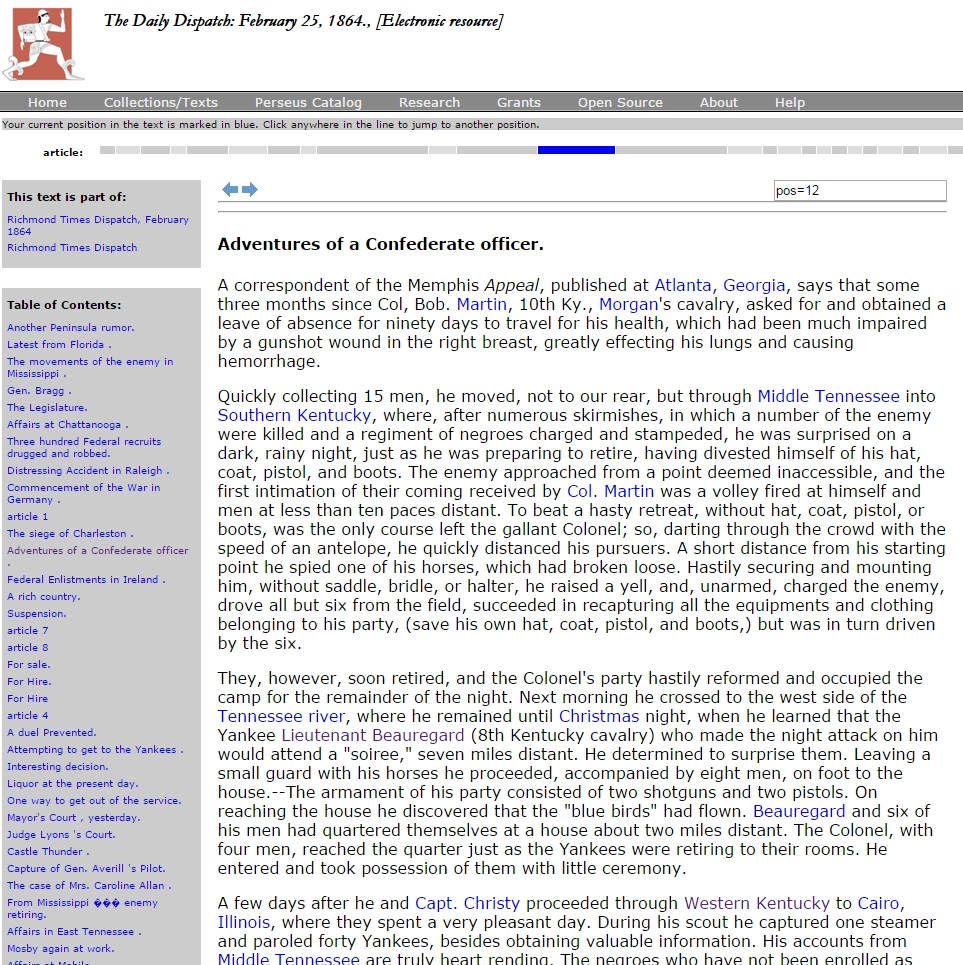

So the Golden Pond story was true to a point. There had been a haul of treasure lost by raiding rebel cavalrymen, but it was not in coins but in the equally valuable property of war—horses, weapons, ammunition, and food. A little extra research in digitized Confederate newspapers wraps up the tale from the other side. The Richmond Daily Dispatch copied a story about the daring escape of Colonel Bob Martin from a “Yankee” ambush into its February 25, 1864 edition.

[Martin] was surprised on a dark, rainy night, just as he was preparing to retire, having divested himself of his hat, coat, pistol, and boots. The enemy approached from a point deemed inaccessible, and the first intimation of their coming received by Col. Martin was a volley fired at himself and men at less than ten paces distant. To beat a hasty retreat, without hat, coat, pistol, or boots, was the only course left the gallant Colonel; so, darting through the crowd with the speed of an antelope, he quickly distanced his pursuers. A short distance from his starting point he spied one of his horses, which had broken loose. Hastily securing and mounting him, without saddle, bridle, or halter, he raised a yell, and, unarmed, charged the enemy, drove all but six from the field, succeeded in recapturing all the equipments and clothing belonging to his party, (save his own hat, coat, pistol, and boots,) but was in turn driven by the six.

Who told the better tale of the fight between Lofton Mitchell’s union home guard and Bob Martin’s rebel soldiers? We’ll probably never know. Within months, the story had evolved in the minds of both loyal and disloyal participants. The accounts from both sides are already working to demonize the enemy, maximize gains, and minimize losses. We are well on the way to the legend of lost Confederate gold sunk in a pond between the rivers.

What all this suggests, though, is that Trigg County was far more bitterly and personally divided than I had ever heard growing up. What these stories tell us is in direct contrast to the 1884 county history, which claimed that “of the people of Trigg who remained at home, both Southern and Union, that they lived in comparative peace with each other. They strove rather to protect than to expose each other to military aggressions and persecutions from either side.” “Both sides agreed to disagree in mere matters of opinion, and wisely left the fighting to the soldiers in the field.”

But what happens when the “people of Trigg” were, like Lofton Mitchell, simultaneously those “who remained at home” and “the soldiers in the field”?

Who were the Union and Confederate sympathizers in Trigg County? Which families, which farms, which communities were divided against their neighbors? It is easy enough to locate the men who served in the respective armies—in fact, there is an excellent book which does precisely that—but Civil War Governors allows a researcher to move beyond the armies to the broader society.

All the men who signed the strident Union petition asking for Lofton Mitchell’s pardon can be considered loyal to the government. Put all the documents from his case together, and we can assemble a list of Lofton Mitchell’s unionist allies. His company commander, H. E. Luten, writes on his behalf, as does his Colonel and State Senator Benjamin Helm Bristow. The process works in reverse, too. Who are the Trigg County rebels? Certainly Elvington DeGraffenreid , John Whitlock, and J. S. McNichols, from whom Mitchell took horses and guns, and probably the witnesses listed in the indictments, too.

In an age before telephone political polling, the correspondence sent to the Governor in Frankfort was a way for state officials to gauge the temperament of the Commonwealth. Petitions, correspondence, and evidence of bitter political (and paramilitary) feuding told officials just how devastatingly divisive their local civil wars within a larger, national Civil War was.

This same sort of information is now equally invaluable to family and local historians who seek constantly to put human faces on people they encounter in dry, bureaucratic censuses and tax records. How excited—and, at the same time, heartbroken—will a researcher be to discover the sad plea of widow Ellen Husk who struggled to feed herself and the young family of her son Frank who was killed serving in the Confederate army? How fascinated will another be to see the names of prominent Trigg County Unionists like R. D. Baker staking their reputation to help a rebel neighbor?

Perhaps, just like there was a kernel of truth to the Golden Pond legend, amidst robbery, guerrilla violence, and community chaos, there was something to that idea that Trigg Countians on both sides of the Civil War tried to stick things out together. There aren’t easy answers in Civil War Kentucky, but there are fascinating and untold stories from every corner of the Commonwealth waiting for the right storyteller.

About the Author: Patrick Lewis is Project Director for the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition. He is a Kentucky native and graduate of Transylvania University. He received his Ph.D. in History from the University of Kentucky in 2012. He worked previously for the National Park Service and has been at KHS since 2010. He is the author of For Slavery and Union: Benjamin Buckner and Kentucky Loyalties in the Civil War, published, Spring of 2015 from the University Press of Kentucky.

About the Author: Patrick Lewis is Project Director for the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition. He is a Kentucky native and graduate of Transylvania University. He received his Ph.D. in History from the University of Kentucky in 2012. He worked previously for the National Park Service and has been at KHS since 2010. He is the author of For Slavery and Union: Benjamin Buckner and Kentucky Loyalties in the Civil War, published, Spring of 2015 from the University Press of Kentucky.