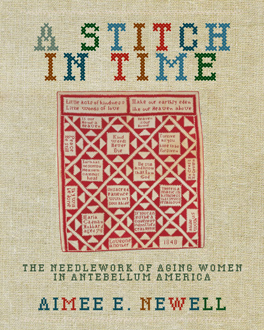

A Stitch in Time: The Needlework of Aging Women in Antebellum America. By Aimee E. Newell. (2014. Pp. 312. $29.95. Paperback. Athens: Ohio University Press. 215 Columbus Rd., Suite 101, Athens OH 45701-1373. http://www.ohioswallow.com/) ISBN: 978-0-8214-2052-2.

A Stitch in Time: The Needlework of Aging Women in Antebellum America. By Aimee E. Newell. (2014. Pp. 312. $29.95. Paperback. Athens: Ohio University Press. 215 Columbus Rd., Suite 101, Athens OH 45701-1373. http://www.ohioswallow.com/) ISBN: 978-0-8214-2052-2.

After years of research, it is customary to become frustrated over the lack of female presence among the records. As the researcher moves back in time, this void becomes even greater, and we struggle to see our female ancestors at all, let alone understand their struggles and passions. This new book by Aimee Newell takes a small window of time (1820-1860) and uses physical objects to shed light on the inner lives of our female ancestors.

The premise is unique in its focus. Yes, previous books have been written that study the sewing habits/creations of 19th century women, but this title narrows the focus even more, by looking at the needlepoint/quilting objects produced by women in their advanced years. So, what can we possibly learn from a book about textile creations from women over the age of 40 within a 40 year time span? Quite a lot actually. According to Newell, the textile is the most enduring form of self expression that exists from this time period. Despite a lack of presence in the records, women have told us quite a lot through the works of their hands.

Part of the reason Newell chose this age group depended upon the social structure that existed at the time. By the age of 40 and beyond, women were more likely to have slowed down a little – enough to reflect on their life, events going on around them, or their family. Perspective brings a lot to the end product as evidenced by textiles that display insight into their creators. Newell cites the prevalence of advanced technique combined with complex imagery or even document worthy details as proof of importance. Instead of writing or painting about their feelings, it was more customary for women to turn to their sewing for expression.

Personally, I found this book to be fascinating. By taking individual examples and researching the women behind the textiles, the reader is gifted with wonderful stories and rich familial examples of strong relationships. In fact, Newell details this element of the process in the term “family currency.” By making an object as a gift within the family ranks, the creator was giving a piece of herself that could be passed down for many generations. The colors, style, motifs, and stitching choices were all carefully selected to represent the relationship or creator.

Newell also notes that the production of such items was truly a labor of love. At this point in their lives, when not many lived past the age of 60 or 70, the act of sewing was doubly hard. Eyes and hands were not as young as they used to be, which made the task at hand that much more difficult. Beyond gifting, some women used this opportunity produce enduring family records. The family vital statistics timeline was a popular motif, and one that genealogists squeal over when one is discovered. In the chapter “Threads of Life” Newell gives many examples of life elements used to pass on the most important dates within a family – much like recording events in a family Bible. As an important example from this time, she uses a popular item from the KHS collections: The Graveyard Quilt by Elizabeth Roseberry Mitchell of Lewis County Kentucky. As family members died, Mrs. Mitchell moved the pre-named coffins into the center area that resembled a family plot. This creation not only speaks to the expression of grief by Mrs. Mitchell, but also provides another great example of the importance of mourning practices of the 19th century, when the average lifespan was often short.

Newell also notes that the production of such items was truly a labor of love. At this point in their lives, when not many lived past the age of 60 or 70, the act of sewing was doubly hard. Eyes and hands were not as young as they used to be, which made the task at hand that much more difficult. Beyond gifting, some women used this opportunity produce enduring family records. The family vital statistics timeline was a popular motif, and one that genealogists squeal over when one is discovered. In the chapter “Threads of Life” Newell gives many examples of life elements used to pass on the most important dates within a family – much like recording events in a family Bible. As an important example from this time, she uses a popular item from the KHS collections: The Graveyard Quilt by Elizabeth Roseberry Mitchell of Lewis County Kentucky. As family members died, Mrs. Mitchell moved the pre-named coffins into the center area that resembled a family plot. This creation not only speaks to the expression of grief by Mrs. Mitchell, but also provides another great example of the importance of mourning practices of the 19th century, when the average lifespan was often short.

Overall, I found this to be a wonderful read, and doubly intriguing for a family historian who loves to learn more about how our ancestors lived. For those of you who suspect there might be a family textile piece lurking in a regional museum, Newell includes a great appendix of items she discovered – arranged by surname – that details their state of origin and current location for viewing. Just like hunting for those elusive family Bible records, researchers should put family textiles on their radar when searching local museums. And as I always remind folks, don’t forget to search our Objects Catalog by surname to see if any of your ancestors’ artifacts were left behind and donated to KHS. To read more about the Graveyard Quilt, and to gain free access to the KHS Objects Catalog, just follow this link: http://kyhistory.pastperfect-online.com/35577cgi/mweb.exe?request=record;id=90C9CB5A-6327-42F0-8085-383648601656;type=101

free sample just need to mind that the